Grave-robber, good doctor

In 1903, a young DMS graduate founded a hospital in Randolph, Vermont. The story of John Gifford and Gifford Medical Center illustrates the depth and breadth of Dartmouth Medical School's impact on the region.

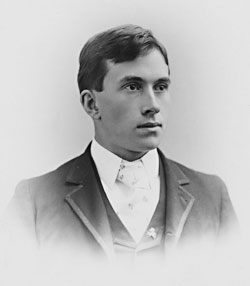

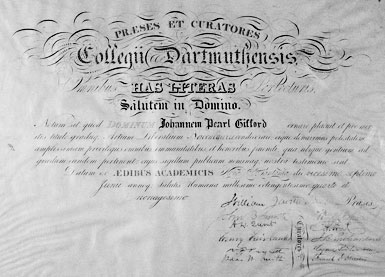

John Pearl Gifford was, to all appearances, an estimable young man. He was an 1894 Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Dartmouth College and the valedictorian of the Dartmouth Medical School Class of 1897. So what are latter- day observers to make of the fact that he was also a convicted grave-robber?

|

Perhaps a little background is in order, by way of answering that question. John Gifford grew up on a farm in Randolph, Vt., and covered himself with academic glory at nearby Dartmouth before returning to practice medicine in his hometown. There—exactly 100 years ago—he established a cottage hospital that was later named after him by his appreciative patients. He was, in other words, a paradigm of the young men from northern New England in whose behalf Nathan Smith had founded Dartmouth Medical School a century earlier.

Yet shortly before collecting his M.D., he was charged (along with a fellow student) of grave-robbing. In light of modern sensibilities, such behavior seems shocking. In fact, the story of the now-venerable institution that John Gifford established has a number of remarkable features; grave-robbing by its eponymous founder, notable though it may be, is arguably the least of them. The best way to explain this unusual aspect of Gifford's otherwise illustrious career is to examine how it fit into the times.

Long before Gifford became one more in a string of Dartmouth Medical School students (and even faculty!) engaged in the somewhat suspect requisition of bodies for anatomical study, body-snatching was a hot topic in New Hampshire. According to medical historian Frederick Waite, the state's legislature hastily passed a statute on the subject of grave-robbing when its members learned that discussions about establishing a medical school were under way up at Dartmouth.

The year was 1796. Nathan Smith had just written to the Dartmouth "Board of Trust" proposing that he be named a medical professor there. In the popular mind back then, the teaching of anatomy in medical colleges was closely connected to grave-robbing. The concept that students might learn about the human body through dissection was beginning to be accepted, but the process of body donation on which today's anatomy-teachers rely did not come into being until the 20th century. That meant medical schools often resorted to dubious means of acquiring bodies—so the legislature's action was hardly surprising.

Students were usually not involved in the practice. It was a school's anatomy "demonstrator" who bore responsibility for procuring bodies, often aided by a faculty member or an independent preceptor eager to do dissections. Waite pointed out that private physicians also engaged in disinterment, quite unsuspected by the populace. Although most, or perhaps even all, members of the medical profession found the robbing of graves "distasteful," Waite noted, they saw it as a necessary evil.

Thus legislators felt they had to take action. Vermont followed New Hampshire's lead in 1804, and by 1818 all of the New England states (five at that time) had a similar law. As soon as Maine separated from Massachusetts in 1820, such a law was passed there, too, in the new state's first legislative session.

The 1796 New Hampshire statute was tough: the penalties for violating it included a fine of not more than $1,000, a prison term of not more than one year, and 39 lashes. But, as historian Waite made clear, enacting laws is one thing; enforcing them is quite another. Most illegal disinterments were probably not even discovered. Arrests and indictments were rare, convictions "yet fewer."

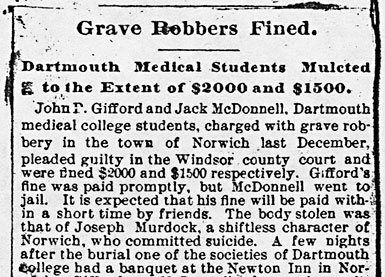

How it came to pass that Gifford and his sidekick, John McDonnell, fell afoul of the law is not clear, except that they seem to have taken no pains at all to hide what they had done. According to the Granite State Free Press, the body of one Joseph Murdock was discovered to be missing from his grave when members of his family noticed footprints in the snow—tracks leading across the cemetery straight for a road (where it would have been easy to load the corpse into a getaway wagon).

Murdock was hardly a leading light of the community; a newspaper article about the grave-robbing described him as "a shiftless character of Norwich, [Vt.]." Even so, his youngest daughter, Harriet, is said to have gone into a swoon when she heard that her father's body had been stolen; she remained unconscious for almost a full day, according to the Hanover Gazette. And a broadside was published proclaiming the "Crimes and Criminals of Dartmouth Medical College. A true account of the monster crime of John P. Gifford, M.D."

| ||

|

The arrest of Gifford and McDonnell was nonetheless surprising. Both were excellent students, while Murdock was apparently a ne'er-do-well. But there seems to have been no doubt that the young men were responsible for the deed, and they duly pled guilty in Vermont's Windsor County Court. Gifford was apparently deemed the worse offender; he was fined $2,000 and McDonnell $1,500. (The monetary penalties had obviously increased in the century since the passage of the first law.)

Despicable though the idea of stealing the bodies of the poor and disenfranchised may seem (the rich were not at risk of "body-snatching," for they could afford to purchase secure burial vaults or to post guards at a grave site until a disinterment would not yield a body of any use to a medical school), the practice was considered by medical educators to be quite justifiable.

And in this case, probably because Gifford and McDonnell were so well thought of—or perhaps because they had even been encouraged by someone at the Medical School to go after Murdock's body—the faculty rallied around to help them.

Gifford's fine was paid promptly on his behalf, but McDonnell went to jail briefly until the faculty voted to advance him the money so he could pay his fine as well. (He was required to take out a life insurance policy for the amount that he was advanced.) This decision was recorded in the faculty minutes, together with a notation that Dr. Carleton Frost was exempted from contributing to the funds raised for McDonnell because he had already "incurred serious obligations in assisting Gifford."

But who was this young man whom Frost had helped save from the ignominy of imprisonment? An eighth-generation Vermonter, he had been born in December 1871 on a Randolph farm that belonged to his parents—John and Celia Gifford. After graduating from Randolph High School, he set off for Dartmouth College, a 40-mile trip that today seems negligible but would then have been a considerable journey. College life apparently suited him. In addition to doing well academically, he played guard on the football squad.

Upon his graduation from DMS, Gifford practiced briefly in North Stratford and Berlin, N.H. Two years later, he was ready to return home. The rest of his career unfolded in Randolph, where he quickly gained a reputation as an outstanding general practitioner and surgeon.

He was no ordinary country doctor, however. Accounts abound of his ongoing study of medicine in Boston and Philadelphia, at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and even in Vienna. Eager to stay abreast of what was new, he is said to have spent part of virtually every vacation furthering his medical education—and that was well before physicians were required to earn a certain number of "continuing medical education" credits to maintain licensure.

Gifford also made the time to read medical journals, even though he kept practice hours that ran from 7:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. And he used what he learned from the literature. In 1911, for example, in an attempt to to save the life of a badly hemorrhaging newborn, he tried a bold procedure that he had read about but never seen performed. The dramatic story is contained in the memoirs of the baby's father, L.B. Johnson, the publisher of Randolph's Herald and News. Gifford drew some blood from the young father, let it stand until the serum had separated and risen to the top, and then injected the serum into his tiny patient. The "remedy worked like magic," wrote Johnson many years later. "Our little one had been saved."

Yet Gifford made his most lasting mark in 1903, by purchasing the grand old Selden Holman house on South Main Street in Randolph and turning it into a hospital. To put this act in perspective, Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital (MHMH) in Hanover was only a decade old at the time. For such a young man (Gifford was just 32) to have such vision and energy is impressive. Yet within two years, not surprisingly, he was exhausted by the strain—both medical and financial—created by his attempt to manage a private hospital while continuing to run his practice.

A seed had been planted, however, and the people of Randolph rose to the challenge of nurturing it. To help their beloved physician save what he had named the Randolph Sanatorium, members of the community organized a holding company in 1905 and issued capital stock worth $7,500. Prominent citizens purchased all of it, enabling the company to buy the hospital and its equipment. Gifford, freed of financial responsibility for the hospital (though he and his wife bought 80 of the shares, valued at $25 each), could then concentrate on his practice and on being the institution's medical director.

Another founding shareholder, and the first president of the hospital, was Colonel A.B. Chandler. A wealthy Randolph resident, he more than once provided significant funding to the fledgling enterprise. In 1909, for example, he bought another $1,000 worth of stock to finance the hospital's first addition.

John Gifford made a further contribution to the medical welfare of the region in 1905, by establishing a training school for nurses. The importance of such an institution is difficult to appreciate today, but at the time formal education for nurses was still a fairly novel idea (Hitchcock beat him to that effort by only a dozen years). The Randolph Sanatorium Nurses Training School did much to professionalize nursing in the region and to improve the status of nurses. When the school closed in 1959, it could boast of more than 200 graduates drawn from across New England and Quebec.

| |

| |

|

Dr. Gifford's satisfaction with what he had wrought is clear in an observation he made in 1920 about how much the practice of medicine had come to depend upon well-trained nurses. "People here have learned that it really does not make much difference what doctor they have, provided they have a good nurse," he said.

The success of the Randolph Sanatorium during its early decades testifies to the need it was filling. After the 1909 addition that Colonel Chandler helped to finance, another major expansion—an annex planned in 1915 but delayed by World War I—was built in 1924. That same year, the shareholders voluntarily turned in their stock certificates so the Sanatorium could be reorganized as a nonprofit corporation.

Such selfless support of the commonweal proved crucial again and again to the hospital's viability. In 1929, a fire broke out in the old part of the hospital (which by then was being used primarily for administrative offices). The clever design of a homemade metal fire door saved the annex, and no harm came to patients. By the spring of 1931, thanks to fire insurance proceeds as well as donations amounting to more than $30,000—a substantial sum for the time— a fine new structure, connected to the former annex, rose on the site and opened for business.

Then, only two years later, the hospital's progenitor died after developing septicemia. Dr. Gifford had nicked his finger while performing surgery on a patient with a streptococcus infection. Even a trip to Boston for treatment at Deaconess Hospital proved futile, in those days before antibiotics. His funeral in Randolph was marked by warm and emotional tributes. The obituary in the local Herald and News stressed the fact that Gifford would be remembered for his "high personal qualities"—including his ability to serve as a "quiet, reserved source of strength to others" and to relieve stress with a "droll dash of dry humor"—as much as (or perhaps even more than) for his obvious and outstanding professional accomplishments. "It is doubtful," the obituary continued, "if there ever was a doctor of medicine and surgery more thoroughly imbued with his high calling than Dr. J.P. Gifford."

Fittingly, both Gifford's name and his philosophy of service to the community have survived. Shortly after his death, the name of the Randolph Sanatorium was changed by the trustees to Gifford Memorial Hospital. (In 1991, the name was altered once more—"Gifford Medical Center" was deemed to reflect more accurately the complexity of the medical institution as its first century was nearing its conclusion.)

That the town of Randolph has benefited from Dr. Gifford's establishment of a hospital there is clear. Less obvious perhaps is the fact that Gifford Hospital was and is part of an important tradition—that of the "cottage hospital." When an altruistic (or entrepreneurial, or practical) local physician opened a private hospital in a village or small town, as often as not the building that housed the "hospital" had originally been a private home, not much more than a "cottage." (And, in fact, many of these rambling structures would later become private homes once again—or, like the Greenhurst Inn in Bethel, Vt., serve as a bed-and-breakfast establishment.)

Several other cottage hospitals besides Gifford's had ties to Dartmouth. Dr. Jo Gallup, one of two students in DMS's first class, established a kind of cottage hospital— which he called an "infirmary"—in the 1820s in Woodstock, Vt. There, students in his Clinical School of Medicine could benefit from the bedside instruction he was a pioneer in believing important. And sometime before 1850, Dr. Dixi Crosby, a surgeon on the DMS faculty, opened what was clearly a cottage hospital in a house on Hanover's North College Street; its closure when he retired in 1870 created a need that was filled only after a fund-raising effort led, 23 years later, to the opening of Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital. Oddly, DMS's 1893-94 catalogue proudly drew attention to the brand-new Hitchcock Hospital but referred to it as a cottage hospital. Its 36 beds made it a "cottage" of considerable size, however. Furthermore, MHMH was housed in an Italian-brick structure built specifically as a hospital, following the latest principles of hospital design, rather than in a converted dwelling.

| |

|

In general, the designation "cottage hospital" meant that the facility was small and served a strictly local population. Having such an institution obviated the need for patients to journey to another town, let alone to a community large enough to have a general hospital. When John Gifford opened his hospital, Hitchcock, clear across the Connecticut River in Hanover, would not have seemed either local or small to residents of Randolph. (Even Lebanon, N.H., which abuts Hanover, established its own cottage hospital—Alice Peck Day Memorial Hospital—in 1932.) The Randolph Sanatorium, though it could not offer all the amenities of the larger Hitchcock Hospital, could provide good care with all the practical and psychological advantages of proximity. John Gifford obviously understood what his hospital—and many others like it— meant to the isolated, rural populations they served.

Yet despite the latter-day name of Gifford Memorial Hospital (now Medical Center), to speak of the Randolph facility as his hospital does a disservice not only to John Gifford's vision but also to the many physicians (currently almost 40) who have been members of its staff through the years. Although Dr. Gifford was "the moving spirit and the main source of strength" of the institution (as his obituary put it), within a year of its founding the facility was opened to other doctors practicing in town. From the start, it was a true community hospital.

Indeed, as critical as John Gifford was to the hospital's formation, other physicians— especially a beloved father-and-son pair— were critical to its continuation. Dr. Frank Angell had opened a practice in Randolph in 1896 (while Gifford was still a student at DMS); he practiced there his entire career and even came out of semiretirement during World War II when the hospital's staff was depleted as doctors were called up to serve in the armed forces. Angell was by then in his early seventies, and the only other doctor on hand to deal with anything that came along—be it medical, surgical, or obstetrical— was Dr. Francis Jennings, who was in his sixties. The two, not surprisingly, became close friends while working together under the demands of carrying the whole (and heavy) load.

By 1928, Angell's son Wilmer— "Dr. Bill"—had begun to work with his father—"Dr. Frank." (The younger man was one of the physicians called away from Randolph during WWII; he served as a senior medical officer on the U.S.S. Boston in the Pacific.) All told, he and his father between them served Gifford Hospital for nearly three-quarters of its first century. An unpublished memoir by Dr. Bill, titled "Vermont Doctor," is in Randolph's Kimball Library—full of stories that reflect the life of the community as well as of its hospital.

The citizens of Randolph are also important threads running through the fabric of Gifford Medical Center's history. During the lean WWII years, the hospital held an annual "bag day," inviting townspeople to donate food or other "gifts suitable for hospital use." The drives netted hundreds of items such as, in 1943, "26 quarts pickle relish" and "13 pillow slips." Local women were trained by the hospital's remaining nurses in Red Cross "home nursing." And, after the war, a fundraising appeal was launched that made it possible to open (in 1952) another 12-bed addition.

An even larger leap forward was made in 1977, when Gifford opened New England's first hospital-based birthing room. Today, the birthing-center concept—a single room where both labor and delivery take place and where the mother can be supported by the baby's father or another family member—is so commonplace that it is hard to grasp how innovative the idea was at the time. The effort was spearheaded by Dr. Thurmond Knight, a family physician at Gifford, and supported by Dr. Lou DiNicola, a pediatrician, and Philip Levesque, the hospital's CEO. Expectant parents responded enthusiastically to having a place to give birth in a home-like setting but with the resources of a hospital right at hand. Pregnant women began trekking to Randolph from well beyond Gifford's customary catchment area. Presentations by Drs. Knight and DiNicola at Dartmouth-Hitchcock and the University of Vermont soon resulted in the two academic medical centers following Gifford's lead in establishing birthing centers. Then if not before, Gifford Hospital was on the map as a place willing and able to be creative in its provision of medical care.

The tradition of a family-centered approach to childbirth continues. Since 1999, the Gifford birthing center has occupied brand-new, specially designed quarters. The hundreds of babies brought into the world at Gifford are testimony to this being one of its greatest contributions to the health and welfare of the region.

| |

| |

|

There have been other expansions, too: the construction of a medical office building and a new emergency room in 1991; the acquisition of a Randolph nursing home, reincarnated as "Gifford Elder Care" in 1993; the opening of an extended-care facility, a new inpatient pavilion, and a facility for hospice patients, as well the new birthing center, in 1999; and the creation of a new ambulatory-care center in 2002, just shy of a century from the time the first patients had walked through the institution's doors. The hospital today has 25 acute-care beds and 20 nursing-home beds.

The expansion has spread beyond Randolph's borders, too. Between 1989 and 1994, Gifford opened or acquired community health centers in four neighboring Vermont towns: Rochester, Bethel, Chelsea, and South Royalton. This has made it possible for doctors who practice in those towns to join the Gifford staff, while continuing to serve their own communities.

It was during this period that the name was changed from Gifford Memorial Hospital to Gifford Medical Center, in recognition of the institution's role as a health-care resource for all 18 towns of the White River Valley. Though descended from the Randolph Sanatorium, Gifford no longer serves only Randolph. It is still very much a community hospital, to be sure, but the community in question is much larger than John Gifford would ever have dreamed possible.

But gradually it became apparent that even more was needed if Gifford was going to continue to offer the best possible care to its patients. Philip Levesque, CEO from 1973 until his death in 1994, began outreach initiatives that resulted in what is today a strong relationship with Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. This relationship takes a variety of forms. For one, Gifford is a member of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Alliance, a network of 11 nonprofit health-care organizations ranging from Upper Connecticut Valley Hospital near the Canadian border to Cooley Dickinson Hospital in Northampton, Mass. These organizations share—and work to help each other achieve—a commitment to improving the quality, efficiency, and availability of health care. But each remains independent, with its own board of directors, its own budget, and ties to its own community.

Today the trip from Gifford to DHMC can be made in less than 45 minutes. But the connections between the two in-stitutions mean that Gifford can offer some specialty care right in Randolph, while maintaining its status as a small community hospital focused on primary care. This is possible because several DHMC specialists travel to Randolph to serve as consultants on a regular basis. Some, like Dr. Douglas James, a cardiologist, put in a day a week at Gifford; others, like Dr. Marc Pipas, an oncologist, are at Gifford less frequently—perhaps twice a month. Still other Dartmouth faculty members—like Dr. Christopher Soares, an ophthalmologist, and Dr. William Minsinger, an orthopaedic surgeon— have their own offices in Randolph.

Not that the role of the consulting physician is always an easy one. The once-a-month consultants need to be aware of the sometimes subtle ways in which a community hospital's mores may differ from those of an academic medical center. And the need to interrupt their ongoing work in Lebanon to travel to Randolph can be disruptive; it is not a schedule or a lifestyle that appeals to all clinicians. But Dr. Thomas Ward—a Dartmouth neurologist who for many years held a clinic at Gifford several days a month—has been a fan of the Randolph institution ever since he got to know it as a medical student. He says his initial skepticism about working out in the region with local doctors was quickly alleviated when he discovered how knowledgeable, self-reliant, eager to teach, and attuned to the community those primary-care physicians were. The mixture of ever-present local providers and specialty care that shows up in their own backyard gives Gifford patients a best-of- both-worlds kind of medical access.

Of course, a trip to the whole array of resources at Dartmouth-Hitchcock is sometimes still necessary. But then, Gifford patients have remarked, it is comforting to find they are often treated at DHMC by the very physicians they have seen as consultants in Randolph—a touch of home away from home. At times, however, even the 45- minute drive to Lebanon is too much. A very visible sign of the cooperation between Gifford and DHMC is the fact that the staff parking lot at Gifford doubles as a landing pad, enabling the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Advanced Response Team (DHART) helicopter to do its impressive, sometimes life-saving work.

Joseph Woodin, the current CEO, is quick to describe Gifford as a special place. Even so, in all honesty, the close relationship between DHMC and Gifford has evolved in part out of necessity—at least from Gifford's point of view. There was a period not long ago when the Randolph institution was in serious financial trouble. A declining patient base and changes in reimbursement practices were major factors. It became tougher than ever during the 1990s for small hospitals to survive, and for several years Gifford wore a tight belt indeed.

| |

| |

|

Yet after a period of adjusting to changes in the health-care world, Woodin feels that Gifford is well positioned to start its second century. What energizes him are the old-fashioned features he believes still drive the place. Volunteers continue to deliver handmade quilts to the Birthing Center; nurses still make time to give back rubs or just sit with patients who need a little extra personal attention; and although "bag day" is an artifact of history, donations of a wide variety of goods and services continue to come Gifford's way. For example, a thrift shop run by the hospital's auxiliary generates more than $100,000 a year for Gifford, while also providing a reliable source of used clothing for the community.

The word "community" keeps cropping up in connection with Gifford. Another piece of evidence that Gifford physicians really are members of the community, one Woodin points to with pride, is that the doctors' home phone numbers are listed in the local directory; they do not hide behind the hospital phone number. They still even occasionally make house calls. And the hospital recently celebrated four years of operating in the black by reinforcing its community ties with a distribution to employees of "bonus coupons" redeemable at local businesses.

While trying to ensure that it will celebrate a 200th anniversary, Gifford is also striving to stay true to the principled philosophy of its founder. A cautionary tale on the other side of the country was reported by the New York Times in August of 2003. Redding Medical Center in northern California grew from a small regional hospital into a prolific heart surgery center; when a five-story addition was built to accommodate the vast increase in cardiac procedures, locals saw it as "a symbol of how a once-sleepy hospital, founded by a single local physician in 1945, had truly entered the big time." But the shocking truth, according to the Times, was that unnecessary surgeries were being done at Redding in pursuit of revenue expectations set by the hospital's for-profit owner.

Such temptations are unlikely to beset Gifford, more mature at 100 years old and still independent. Like its much-larger neighbor, DHMC, Gifford remains a nonprofit institution— meaning its aim is balanced books but not dividends for investors.

Gifford benefits from its ties to DHMC, of course, and from having accepted a broader geographic mandate than it once had. But it remains a true community enterprise. John Pearl Gifford might not recognize some of the modern equipment in "his" hospital, but he'd surely recognize the manner in which it's used in his community's hospital.

Medical historian Constance Putnam has written about many aspects of Dartmouth medical history for the pages of this magazine. She holds a Ph.D. from Tufts University and is the coauthor of the definitive biography of Nathan Smith, the founder of Dartmouth Medical School (Improve, Perfect, and Perpetuate: Dr. Nathan Smith and Early American Medical Education), as well as the author of a forthcoming, full-scale history of DMS (The Science We Have Loved and Taught: Dartmouth Medical School's First Two Centuries), which is due out from University Press of New England in the spring of 2004. Source citations for the quotations in this article are available upon request to Dartmouth Medicine (see page 2 for contact information). The images are courtesy of the Dartmouth archives and Gifford Medical Center.