Sports and Medicine

|

|

Jack Turco . . . Hockey . . . Endocrinology |

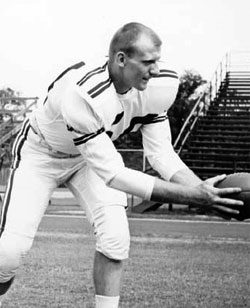

Dr. Kenneth DeHaven, a 1963 graduate of DMS, still scouts medical schools rather than football fields or hockey rinks for young doctors to train with him at the University of Rochester's Division of Sports Medicine. But at the same time, he figures it can't hurt if an aspiring orthopaedic surgeon comes with some high-level competitive sports on his or her curriculum vitae.

"I've never seen [an applicant] yet who was a good athlete who was not a good surgeon," says DeHaven. "They've grown up being used to having their body do what their mind wants them to do. And they're used to performing under pressure.

|

|

Kris Karlson . . . Rowing . . . Family Medicine |

"Both qualities are crucial in medicine— especially in surgery," he adds. DeHaven ought to know: He tuned up for medical school, in part, by blocking and tackling for legendary Dartmouth College football coach Bob Blackman in the late 1950s.

"I had my opportunities to make big plays along the way and managed to pull them off," says DeHaven, who wrapped up his football career as a center on offense and a linebacker on defense by serving as captain of the Dartmouth team in 1960. "I realized that when the pressure's really on, I can make that allout effort. Just your normal level of professional people who haven't been in that kind of situation . . . when the time comes that they feel they have to do their all-time best, they come apart.

"Having that kind of experience has been invaluable to me in all walks of life," De- Haven concludes.

The experience of competing in highlevel sports while also juggling college-level studies appears to come in handy even as preparation for medical school. The late Dr. Marsh Tenney, a former dean of Dartmouth Medical School, certainly noticed the connection.

|

"More than one of [Tenney's] trainees during the late 1950s and through the 1960s remember him stating . . . that he had looked at admissions criteria of DMS students over the period of a few years and then correlated various measures with the individual student's subsequent performance in both the basic science and clinical years," explains Dr. Eugene Nattie, a 1968 DMS graduate who was one of Tenney's trainees and is now a professor of physiology at Dartmouth. "To his surprise," Nattie goes on, "he found that the admissions datum with the highest correlation was whether or not the student had won a varsity letter."

Nattie adds that although the DMS student body back then was made up mostly of white men who'd done their undergraduate work at Dartmouth College, he and Tenney, "among others, interpreted the datum as suggesting that a student who was involved in a very major time commitment like a varsity sport would then be able to perform in medical school at a higher academic level."

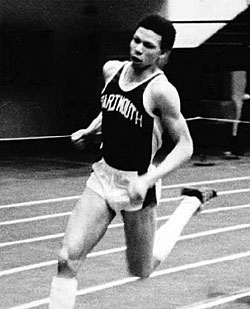

Indeed, a number of DMS graduates have found that the lessons they learned through sports have gone beyond outsprinting opponents to the finish line (as Dr. Ray Blackwell did for the Dartmouth College track team in the late 1970s) or racing faster than anyone else down an icy ski slope (as Dr. Cara Walther did for Middlebury College in the late 1980s).

"You get used to multitasking, between training for NCAAs and studying for an exam in organic chemistry," says Walther, a 1993 DMS alumna who is now an orthopaedic surgeon with a sports-medicine practice in Bend, Ore. "It's like the saying goes: The more that's asked of you, the more you get done. When you're that motivated, and striving for excellence in athletics, it carries over into everything else."

Even after a tear in the anterior cruciate ligament of one of her knees ended Walther's competitive skiing career—and simultaneously attracted her to orthopaedics—she found that as a medical student she couldn't just sit still and study all the time. The solution? Coaching young skiers in the Upper Valley's Ford Sayre Ski Program. "Even though I wasn't racing myself," Walther says, "coaching was almost a full-time job on top of my medical training. But I really would have felt a void if I hadn't coached."

|

|

Cara Walther . . . Skiing . . . Orthopaedics |

|

"You get used to multitasking, between training for NCAAS and studying for organic chemistry," says Walther. "When you're motivated in athletics, it carries over into everything else." |

|

|

Jack Turco . . . Baseball . . . Endocrinology |

More recently, Walther took time off from her practice—where she mends the damaged knees and shoulders of skiers, kayakers, and climbers attracted to the outdoor-recreation mecca of Oregon's Cascade Mountains—to tend to the medical needs of the U.S. Alpine Ski Team during the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City. "I feel fortunate I've been able to incorporate one of my great loves with my profession," she says.

Blackwell, a 1987 DMS graduate, found it more difficult to incorporate his love for track with the demands of medical school. But thanks in part to the discipline and the time-management skills he developed as an undergraduate, the Delaware-based cardiac surgeon is now catching his second athletic wind as the one of the fastest American men on the masters track circuit.

"When you're competing in college, you have to try to keep up with your studies," Blackwell says. "You make a schedule, and you keep to the schedule. I knew that my work had to be done before I went away for a meet. It was difficult to do on the road. That pattern stuck with me through medical school, and it carried over with my residency training.

"By then," Blackwell says, "I wasn't competing anymore, but the discipline I learned as an undergraduate got me through my surgical residency."

More than 15 years later, that discipline still gets Blackwell through some pretty long days. He usually rises ahead of the sun—and ahead of his wife (and DMS classmate), Dr. Wanda Francis-Blackwell, and their two daughters— first to read for an hour, then to work out for another hour at either a nearby track or in the weight room to stay in shape for masters competition.

|

|

Alan Rozycki . . . Football . . . Pediatrics |

"And then I start my workday," Blackwell says. "It's an enjoyable day for me. I've already done something for myself, and now my patients have my attention." Not long after turning 40, Blackwell started winning attention on the track—again. A member of the Sprint Force America track team, he ran the indoor 400-meter dash in 49.4 seconds in 2000, setting a new world record for men aged 40 to 44. This past May, he graduated into the 45-to-49 division, which will give him a chance to chase some new records.

Blackwell says running on the masters level "has been rewarding, more for the people that you meet than anything. But there's still the satisfaction of competing. When you step on the track, you're there to produce. No one's going to give you that race. You've got to earn it. You have to run."

Blackwell missed that sense of urgency after giving up one dream—running the 400 at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul—to devote his energies to another dream—attending medical school so he could learn to repair damaged hearts. "When I stopped competing, I was kind of disappointed," Blackwell admits. "I had big aspirations, but at some point you have to make a choice.

"I had my time down to 46 seconds, but I had to get lower than that" to have a chance of qualifying, Blackwell explains. "To get from that level to the next would have been total commitment. I could have made the Olympic Trials, but going to the Olympics would have been a long haul. And as much as I loved track and field, cardiac surgery was the number-one thing for me."

The idea of heart surgery had taken root while Blackwell was growing up on a tobacco farm in Virginia, and the goal grew in importance after his father and sister underwent heart operations. It didn't flower, however, until a program called "A Better Chance" allowed him to finish high school in suburban Connecticut.

"In Virginia, I didn't know the steps I needed to go through to get where I wanted to go," Blackwell says. "In Connecticut, the steps became clearer." Blackwell followed those steps to Dartmouth College, where he majored in sociology, captained the track team, and learned to balance school and sports. But after going on to DMS and trying for two years to continue to strike that balance— including finishing eighth in the indoor 400 at the U.S Championships in 1985—he made his choice. "On the farm in Virginia, we grew up surviving, doing the best with what we had," Blackwell says. "My family sacrificed a lot so I could go to school, and at some point I had to ask myself, 'What are you here for?'"

In 1994, three years before joining the DMS faculty as an assistant professor of community and family medicine, Dr. Kristine Karlson had asked herself a similar question. By stretching her medical studies at the University of Connecticut in Farmington over an extra two years, she had found the time to train for—and win—three world championships in rowing: the lightweight single scull in 1988 and both the single scull and the double scull in 1989.

|

|

Ray Blackwell . . . Track . . . Surgery |

|

DeHaven's Teamwork skills have been tested by his leadership roles with a number of medical societies — including the presidency of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. |

|

|

Ken DeHaven . . . Football . . . Orthopaedics |

And the following year—during which she graduated from medical school—Karlson found a new partner for the open-weight double scull and picked up a bronze medal at the world championships. But while doing her residency at UConn and continuing to row, she found the double duty taking a toll. She and her partner finished eighth at the worlds in 1991 and failed to make the 1992 Olympic team. Karlson then found a seat in a four-woman boat, but it finished fifth that year at Barcelona.

The resulting burnout prompted Karlson to give up competition so that she could complete her residency. And yet within two years, the sirens of Olympia were once again singing in her ear. She decided to give it one more shot when the Olympic organizers added a lightweight double event to the rowing competition for Atlanta in 1996. But at the trials, where only one boat makes the cut, Karlson took the hint after coming in second.

"I realized that if I were to continue competing, I would be competing against myself. That's too stressful," she says. "The intense competitor is gone now. I don't know if it's a matter of putting it aside. It's just over."

The competition may be over, but not necessarily the fire that fueled it. That may explain the presence of so many former athletes in medicine. "I think it's the intensity," Karlson says. "Clearly, these people do everything in their lives with intensity."

Sharing that intensity with teammates can also help to build collaborative skills that doctors later find useful in practice. Ken De- Haven grew to appreciate the group chemistry he'd learned on the gridiron when Rochester's sports medicine division, which he founded in 1975, started growing with the boom in high school, college, professional, and recreational sports.

Those teamwork skills have also been tested by his leadership roles with a number of medical societies over the last three decades—including the presidencies of the 20,000-member American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, of the Arthroscopy Association of North America, and of the International Society of the Knee.

Rochester's Division of Sports Medicine "has progressed from being a one-man band to a division with six full-time attending physicians," DeHaven explains. "In whatever I do, I always try to lead by example, as I did while I was playing. To build consensus, you've got to have the team pulling in the same direction."

Dr. Marc Gautier learned some similar lessons—along with good study habits—from playing basketball for Dartmouth in the late 1970s. "We didn't win many games or any championships," says Gautier, a 1986 graduate of DMS who is now an assistant professor of medicine at Dartmouth, "but we played hard and played like we wanted to win. And we worked hard in the off-season to get ready for games that we wouldn't be playing until December.

"That's what carries over for me," says Gautier, who specializes in oncology, "certainly in working with people with cancer. You're going to work like a dog to make the patient's life better.

"When you play a team sport," he explains, "you do a lot of weighing of what's best for you versus what's best for the team. It's a more effective way to work with other people. You're so dependent on everyone else. It's a good model for moving into health care."

Good but not perfect, in the eyes of Dr. Alan Rozycki, who followed Ken DeHaven's blocks to set a number of rushing and scoring records during his own Dartmouth College football career.

|

|

Leanne Eberly-Jordan . . . Rowing . . . OB-GYN |

|

"When you play a team sport," Gautier explains, "You do a lot of weighing of what's best for you versus what's best for the team. It's a more effective way to work with other people." |

|

|

Marc Gautier . . . Basketball . . . Oncology |

"I'd like to believe that I learned teamwork and therefore became a better team leader, but I don't think that the teamwork of an athletic team really translates to the teamwork needed in the bureaucratic setting of a medical center," says Rozycki, a 1963 graduate of DMS who has been a member of the pediatrics faculty at Dartmouth since 1972. "Sports is very action-oriented," he ex- plains. "Patience is needed, of course, but the outcomes are often determined by how hard the team works—[by] dedication and determination."

Outside the sports arena, says Rozycki, "in many organizations, it is my impression that people who have had sporting team experience become frustrated by the inaction, apparent lack of teamwork, and a lack of successful outcome following hard work. A large bureaucracy is much more complicated than most sports teams."

Perhaps because her Durango, Colo., obgyn practice is more intimate than a huge hospital, Dr. Leanne Eberly-Jordan does see some parallels between her days of rowing in four- and eight-woman boats for Dartmouth in the mid-1980s and her life today.

"The interpersonal skills you develop in crew have been very helpful," says Eberly- Jordan, who is also a 1989 graduate of DMS. "I work well on teams and committees. And in my practice," she adds, "it's a matter of managing a whole team—nurses, front-office staff, back-office staff."

Dr. Jack Turco is also still applying, and reinterpreting, the lessons that he absorbed playing two varsity sports— hockey and baseball—at Harvard. More than 30 years later, those lessons go beyond the revelations he gained from passing the puck instead of shooting and from bunting to move a runner along instead of swinging for the fences.

"Teams are kind of a microcosm of the world," maintains Turco, an endocrinologist who is a '74-79 housestaff alumnus of Dartmouth, an associate professor of medicine at DMS, and the director of the Dartmouth College Health Services. "You had the BS artist, and you had somebody you could trust. It was a good place to grow, to expand your horizons in a somewhat controlled environment. As a player, where you're dealing with a lot of personalities, you learn to deal with different people and different situations. That applies in dealing with patients, too. You learn to adapt to different situations based on someone's personality and the circumstances."

And for Turco, happy endings on the ice or the diamond weren't always the best teachers. "One of the most valuable lessons you learn is how to lose, how to fail," Turco says. "I remember I cried the first time my Little League team lost. As you go along, you have setbacks that make you think the world is over. Then the next day, you get up and you realize it wasn't the end of the world."

In medicine, of course, former athletes are playing for higher stakes than just championship trophies or newspaper coverage. But as the father of two sons and a daughter who all played for winning soccer and hockey teams at Hanover High School and in college, Turco worries about students who move into adulthood on a wave of athletic and academic success—for which their parents ran interference.

"A lot of kids are insulated from setbacks," Turco says. "A colleague of mine said not long ago that the students he has are incredibly bright and talented, but one thing they've never done is fail.

"You've got to have setbacks," he says. "That's where you learn about yourself."

Corriveau has been a sportswriter for the Valley News, the Upper Valley's daily newspaper, since 1987. A graduate of Northeastern University's journalism program, he has written previously for Dartmouth Medicine about a DHMC grand rounds presentation by Sir Roger Bannister, a British neurologist and the world's first sub-fourminute miler; about several Dartmouth-affiliated runners who qualified for the centennial Boston Marathon; and about a Dartmouth medical student who competed in the Hawaii Ironman Triathlon. Appreciation is extended for assistance in locating photographs for this article to the Offices of Sports Information at Dartmouth, Harvard, and Williams, and to several of the athletes interviewed.

If you would like to offer any feedback about this article, we would welcome getting your comments at DartMed@Dartmouth.edu.