Vital Signs:

Two DMS researchers establish and endorse drug information box

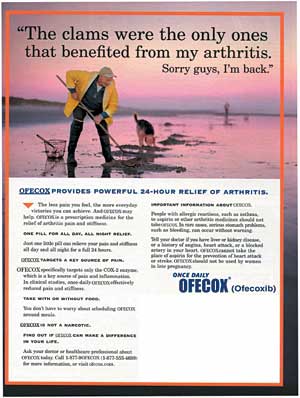

"The clams were the only ones that benefited from my arthritis," says the clam digger in a Vioxx advertisement.

The first page of the magazine ad is a splash of color. The flip side, however, is a sea of blackand- white text, known as the "brief summary," detailing the side effects of the drug (the brand-name version of rofecoxib). Even if average consumers read and understood this summary, they would still not gain a realistic sense of how well the drug works, according to Drs. Lisa Schwartz and Steven Woloshin. They are both DMS associate professors of medicine based at the VA Medical Center in White River Junction, Vt.

"[Direct-to-consumer drug advertisements] talk about bene- fits in these vague ways, but it's rare that you'll find data," explains Schwartz. "If you do find data, it's rare that it's in a balanced, understandable format. How can you decide whether it's worth exposing yourself to harms, if you don't know what you are getting?"

For the past few years, the husband-and-wife research team has been urging the FDA to ask pharmaceutical companies to include efficacy data—information about a drug's benefits, not just its side effects—in all printed direct-to-consumer ads. (See the Spring 2002 issue of Dartmouth Medicine for details of their earlier study on the subject.) While the FDA expressed strong interest in Schwartz and Woloshin's proposal, the agency wanted to know if patients could understand and make use of efficacy data.

|

| Everything in the ad pictured is real except the name of the drug. Two DMS researchers would like to see the information box below be a part of such ads. |

|

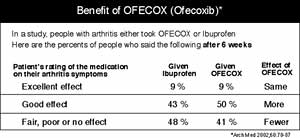

Box: To answer the FDA's inquiries, Schwartz and Woloshin collaborated with Dr. H. Gilbert Welch, a DMS professor of medicine, to adapt three real-life advertisements for the drugs Vioxx, Pravachol, and Plavix. They changed the names of the drugs and created two versions of each ad—one with a benefit box and one without it. (See below for the pseudonymic Vioxx ad and information box.)

The efficacy data for each information box was gleaned from the randomized trials conducted to gain FDA approval of the drugs. After viewing each version, participants were asked to rate the effectiveness of the drug; they were also asked how useful and understandable they found the benefit box. In addition, participants' ability to understand the facts in the box was evaluated with a test.

The results were dramatic— 93% of respondents preferred the benefit box to the "brief summary," and 95% to 97% answered the test questions accurately. But perhaps the most intriguing finding was that the box changed participants' perceptions of how well a drug works.

Lower: "Perceptions of drug effectiveness were much lower for ads that incorporated the benefit box than for ads that did not," wrote Schwartz and Woloshin in their article, published as a Web exclusive by the journal Health Affairs. For example, the percentage of participants rating Vioxx as "extremely or very effective" dropped from 65% to 28% after they saw the benefitbox version of the ad. "The presence of the benefit box also caused many more respondents to correctly rate the effectiveness of [Vioxx] as being 'about the same' as that of ibuprofen," the authors continued.

But Schwartz and Woloshin noted that participants failed to understand the significance of certain data. For example, when study respondents looked at the 3% mortality rate in people taking Pravachol, a cholesterol-lowering drug, and the 4% mortality rate in people taking a placebo, they underrated that onepercentage- point difference, not recognizing that the drug actually reduced deaths by 25%.

"The paper by Woloshin and colleagues makes some intriguing suggestions," wrote Pat Kelly, a vice president of Pfizer, in an opinion piece in the same issue of Health Affairs. "But it also shows that many consumers lack the context required to judge if a medicine that reduces overall mortality over five years from 4% to 3% is a medical miracle or a waste of money."

Interpret: Schwartz argues that lay individuals can and will be able to interpret such data, if they are exposed to it. "When [the nutrition facts label] came out, a lot of people wondered whether people could make sense of this information," she says. "There has to be a learning curve," she insists.

So which is worse: overestimating or underestimating the benefit of a drug? "It's hard to know which direction is more harmful," says Woloshin. "The idea here is to help [people] get accurate estimates."

The team presented its findings to the FDA in September 2003, but the agency has taken no steps to incorporate drug benefit data into direct-to-consumer ads nor to conduct a national test of the more detailed drug information box that Schwartz and Woloshin originally proposed.

So the pair are making plans to conduct a larger study on their own, while also doing their best to raise public awareness about the issue.

Jennifer Durgin

If you would like to offer any feedback about this article, we would welcome getting your comments at DartMed@Dartmouth.edu.