President Wheelock & the Smallpox Caper

By Seymour E. Wheelock, M.D.

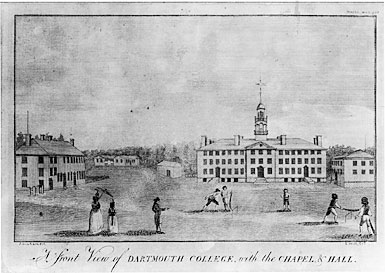

Back in 1776, the Dartmouth campus was a hotbed of dissension about the advisability of being inoculated against smallpox. Ironically, it's a topic that is once again in the news in these days of bioterrorist threats.

|

|

Image: Dartmouth College Archives The portrait above of Dartmouth's founding president, Eleazar Wheelock, was the work of American artist Joseph Steward. He was commissioned to paint it by the Trustees of the College almost 20 years after the events described in this article and more than a decade after Wheelock's death. The painting itself is larger than life-sized, being nearly seven feet tall. The image at the top of this page depicts "confluent variola," a case of smallpox so severe that the lesions merge into each other. It is from an 1845 medical book titled "A Theoretical and Practical Treatise on the Diseases of the Skin." |

Leon B. Richardson, the author of a 1932 history of Dartmouth College, was pithy to the point of understatement when he summed up a nearly hysterical dispute that took place in Hanover starting in the summer of 1776. "It had to do with smallpox," Richardson wrote. Indeed it did.

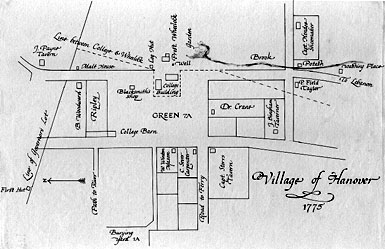

Dr. Laban Gates, one of several physicians in the town of Hanover, N.H., became engaged that longago summer in a bitter battle with Eleazar Wheelock, the president of Dartmouth College. The dispute centered on whether the students at Wheelock's institution, then a mere seven years old, should be inoculated against smallpox.

Dr. Wheelock, whose health was, by his own account, "so despairing that I am in an infirm and broken state," lived in terror of the dread disease. His agitation was so extreme that he canceled a fundraising trip to England, which he considered a cesspool of smallpox. And he was as determined in his opposition to inoculation against the disease as he was fearful of contracting it. His unyielding stand against inoculation pitted him against Hanover officials as well as against the irascible Dr. Gates, who had hung his shingle in town just two years earlier, in 1774.

The controversy between Wheelock and Gates began when Gates inoculated one or more students with the feared virus without telling anybody in authority, most particularly Wheelock himself. But, as so often happens in a small town, Wheelock learned of the act. The ensuing quarrel became hot news in Hanover, despite the portentous political and military events—the early campaigns of the Revolution, of course—that were unfolding elsewhere in the colonies.

Wheelock's fear was not entirely misplaced. In those days, inoculation was little more than Russian roulette. Vaccination is now so common and safe, and the microbial basis of infectious diseases so well understood, that it may be hard to imagine the mind-set of people in 1776. But English physician Edward Jenner's discovery of a reasonably safe and effective method of inducing immunity against smallpox—using a vaccine made from the similar but less-virulent cowpox—was still 20 years in the future. (Both inoculation and vaccination involve the introduction of a foreign substance into the body for the purpose of stimulating immunity. Inoculation is an older, broader term, covering any method of introducing any infectious agent. Vaccination— which comes from vacca, Latin for "cow" —originally referred only to inducing protection against cowpox and its close cousin, smallpox. It is now commonly used to describe immunization against any disease by injection of a vaccine made from an attenuated, or killed, microorganism.)

Of vaccination and variolization

Nevertheless, for centuries before Jenner's discovery, physicians were aware that survivors of many infectious diseases were immune to further infection. Doctors had long introduced the contents of smallpox lesions into scratches on the skin of healthy individuals. They hoped to induce a mild or moderate form of the disease, with less fever and fewer chills and "pocks," while still producing immunity. In reality, many fatal cases resulted from this form of inoculation—which was initially called "variolization," since the disease is also known as variola. But despite the fatalities, the procedure had the feeble imprimatur of Cotton Mather and Zebediah Boylston, who had introduced variolization in Boston in 1721. And more to the point, it was all that they had to fight the dread disease.

But President Wheelock was not a believer in playing that version of Russian roulette. He came down hard on Gates, penning a stern denunciation of the doctor's defiance of his office's authority. The president's diatribe is worth quoting in its entirety:

Dartmouth College

August 5, 1776

Whereas there has been for a few days or weeks past, clandestinely carried on, a design of communicating the small pox by innoculation among the Students of this College, and a number had received it without consulting with the President, or any of the Authority of the College, or even so much as acquainting the President, or giving him the least opportunity or advantage to consult for his own, his family's, or Neighbours' safety in such a time of danger, or acquainting any of the good People of the Neighbourhood therewith, that the matter might be submitted to the inspection, direction, & provident conduct of suitable Persons appointed for that purpose.

And whereas Doctor Laban Gates, notwithstanding any obligations to the contrary in point of gratitude, and without the least respect manifested to the President's office, age, or great bodily infirmities, which under the probability next to certain that the distemper would prove fatal to him if he should take it; and also without the least regard to the reputation, increase, & wellbeing of this Seminary, or the peace & comfort of Parents at a distance who have Children here; and notwithstanding that he, the sd. Gates, had never had the small pox himself, nor any more than a theoretical acquaintance with it, or what treatment would be suitable for those who should have it, did procure some of the infection & communicate it to a number of the Students, or at least supposed he had communicated it (tho it is not certain it had not lost its virtue) and was understood to have a design to proceed in such a dangerous & unadvised manner of innoculating.

And whereas several of the Students who were forbid to receive it in that manner have thereupon, without counsel and of their own accord, gone to receive it in a neighbouring hospital, and in such a hasty & unadvized manner, as together with the before-mentioned proceedings, inspired a fear that due care will not be taken by all, that they be so effectually cleansed as not to expose the society to receive it from them on their return to College.

Wherefore I have, with the advice of such of the authority of the College as could be had on this emergency, decreed & determined—

1. That Doctor Laban Gates be forbid, and he is hereby forbid, entering any room in the College, or any under my controul in the Neighborhood, on his return from innoculation, without leave therefor first obtained from me, and he being now taken under the care of the Committee of Safety to be dealt with according to his merit, I leave what has passed to their determination.

2. That no Student shall invite sd. Dr. Gates on his return from innoculation to sit, or suffer him to be in his room, without leave therefor from the President, or abet, countenance, or encourage him in any opposition to the aforesaid orders on the penalty hereafter mentioned.

3. That none of the Students on their return from innoculation shall on any occasion intermix themselves with other Students until they have first obtained sufficient certificate of safety therein, and have so removed all fears as that the President shall judge it safe for them.

And these foregoing orders shall be strictly observed on penalty of immediate expulsion from College and all the priviledges & honors of the same.

By Eleazar Wheelock, President

Dr. Gates was cowed by the mandate from on high. He swore not to repeat the offense, which had been conducted "without sober reflection," and the matter was thought to be resolved. But not for long. President Wheelock may have been guilty of overreaction at the time, but soon the unfolding war inflamed the public's fear of plague and pestilence. An outbreak of smallpox in George Washington's Continental Army—bred in the crowded military camps and spread by the movements of soldiers— eventually took more lives than were lost in battle. Before long, the members of the Dartmouth community, particularly the students, were insistent that they were due the "protection" that inoculation provided to those in whom a case of smallpox was induced—assuming they survived.

|

Of petitions and pesthouses

In January, eight students and 15 villagers petitioned to be inoculated and housed during their illness in a vacant miller's house "a mile and one-half from any dwelling." This damp and uncomfortable pesthouse (as such places were called) had several rooms—one of which Wheelock quickly reserved for himself and his wife, fearing that he had been exposed to the disease. After all, the petitioners claimed that they had had contact with unidenti- fied carriers within the community.

There was immediate turmoil over who should enter the pesthouse—only students, or villagers as well. Wheelock was outraged at the suggestion that townspeople be housed with students, since he regarded the miller's house as a College outbuilding. His anger appears to have been redirected—he now seemed less intent on preventing inoculation of "his" students than on ensuring that he made the decisions about their care.

Then town officials proposed that the pesthouse be moved to a "hut" eight miles away in Lyme, where facilities and even bare necessities were nonexistent. The president was even more furious at this suggestion. And his animus increased further still when he was told by a member of the Hanover Committee of Safety, "We will take your mansion house for a hospital if we see fit."

The feud was complicated by the troublesome fact that the Committee of Safety numbered among its members Wheelock's son-in-law Bezaleel Woodward, also a Dartmouth Trustee, and Aaron Storrs, his own certified public accountant and business agent. The College was clearly a house divided.

Of authorities and (in)action

President Wheelock, despite his advancing age and increasing ill health, fanned the flames of his dispute with the Hanover authorities all through 1777. He even sought the allegiance of the Grafton Presbytery and filed an eight-point "whereas" complaint against his son-in-law and four others, claiming they were "meddling with the authority of the president of the College as set forth by royal charter." The Presbytery took no action either way.

Dartmouth College Archives | |

Evelyn Marcus | |

|

Undaunted, Wheelock lobbied the College's Trustees, tutors, and students. By now, the latter were all demanding inoculation as well as appropriate supervision and care at the mill. The senior students, on March 5, delivered themselves of a feverish indictment of the town's stand:

The inhabitants of this town of late in their votes and proceedings relative to the affair of the smallpox have most injuriously encroached upon the privileges and immunities of this College—insulated the jurisdiction of the Trustees—and reproached your character as President. Which conduct, if passed over in silence, will invalidate the whole Authority of this Institution, diminish its honors, and finally destroy all its immunities.

The students asked the local authorities to restore the dignity of the College, threatening otherwise to seek academic asylum elsewhere—"for if the rights and privileges of this College cannot be asserted and maintained in a manner superior to what they have been this winter past, we think a diploma granted here not worth the reception."

This intemperate appeal matched Wheelock's own distorted view of the situation. Indeed, he, too, issued an ill-considered threat to move the College to western New York State's Mohawk Valley—to a large tract of land that was then owned by the patriot party of New York and that had formerly been the estate of Sir William Johnson, a hero of the French and Indian War.

It was a frail scheme, energized by passions uncharacteristic of Wheelock's measured judgments in years past. But he was convinced that Dartmouth's charter endowed the institution with all the immunities so fiercely protected by universities in the United Kingdom, and consequently that the school was beyond the control of civil authorities— even in matters of public health.

So Wheelock continued to shrug off the genial, sober urgings of his Trustees that he get on with his life, even when they said they believed him enough of a Christian to forgive the complaints he had filed against them in June of 1777.

Despite the rapid escalation of the war with Britain, the dismal weather that winter ("such a large body of snow even yet in all our meadows, which insures scarcity of breadcorn"), and the inexorable decline in his own health ("I have long been in a broken state of health and have been able to preach with much difficulty about half the time"), the College's president placed the inoculation flap on the agenda for several more meetings of the board. Each time, the tiny bureaucracy artfully dodged the issue.

Finally, by August of 1778, Eleazar Wheelock had become too sick and weary to continue the battle. Worn out by the effort to keep the College running during wartime, he threw in the towel and turned his mind to other matters—such as raising tuition to 25 shillings a quarter, room to 6 shillings a quarter, and board to 10 shillings a week.

Inevitably, both within and without the College's jurisdiction, inoculation continued at a rapid pace, fueled by near-panic about smallpox. After all, General Washington had ordered the immunization of his troops—what better assurance could there be of the procedure's safety?

Of blisters and bad news

It was 1800—23 long postwar years during a time that historian Jonathan Sassi has described as "a republic of righteousness"—before Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse introduced the American "publick" to Edward Jenner's "kine-pox" vaccination. Even so, countless venerable cemeteries bear witness to the continuing devastation wrought by this ferocious microbe, which Nobel laureate Peter Medawar has called "merely pieces of nucleic acid surrounded by bad news."

Eventually, however, the tide began to turn. In his 1813 Dispensatory, Dr. Peter Smith (no relation to Dartmouth Medical School's founder, Dr. Nathan Smith) judged vaccination to be "fully established as an antidote against the pox, and if this innoculation shall be attended to, the rising generation will scarce ever see the truly deplorable and affecting scenes of good folk dying or torn to pieces by the ravening and hideous blisters."

Dr. Smith described his method of preparing the immunization: "Carry the infection on a cotton thread, absorbed full of the watery slime from a blister, dried moderately before the fire and dropped into a phial. The thread may then be cut to pieces at will and moistened with spittle on a bit of glass. The bigness of half a pin's head will do to vaccinate a person." He administered the vaccination on the wrist, cheerfully declaring, "If you must have a sore arm, it is better to have it there!"

Of microbes and Mandans

A less felicitous chapter in the fight against the disease came as a result of the young nation's steady struggle westward. Smallpox caused the partial— and sometimes total—decimation of the Native Americans tribes that had occupied the continent for centuries. Even when white settlers' hands were extended in peace to the tribes they encountered, those hands were contaminated by one of the most hardy and vicious viruses the world has ever known. And it was a microbe with which the Native peoples had never before had contact and so against which they had developed no immunity. The results were devastating.

|

It is hard to imagine a more sorrowful occasion than 19th-century painter and author George Catlin's description of the death by despair of his friend Four Bears, chief of the Mandans: "This fine fellow sat in his wigwam and watched every one of his family die about him, his wives and his little children. He walked out around his village and wept over the final destruction of his tribe, his braves and warriors. When he returned to his lodge he covered his whole family in a pile with a number of robes and, wrapping another about himself, went out upon a hill at a little distance, resolved to starve himself to death.

"One thing is certain," Catlin concluded sadly. "As a nation the Mandans are extinct, having no longer an existence." A member of another ravaged tribe put it this way: "The fur traders opened a bottle and let the pestilence destroy the whole of us."

Yet unfortunately, Catlin pointed out, the Native Americans were very wary of—and, sadly, successfully resistant to—the efforts that were made to vaccinate them. They regarded the attempt as a trick to further subdue them, even when they were faced with evidence that vaccination worked among a few of their number.

Of Somalia and September

In October of 1977—just over 200 years after Eleazar Wheelock's fulminations against Laban Gates—a young Somalian presented himself at the dispensary of a hospital in Merca, a city near Mogadishu on the Somalian coast.

His name was Ali Maow Maalin, and he had been diagnosed a week or so earlier as having chicken pox. But on this visit, it was determined that he was seriously ill with smallpox. When he recovered, he learned that he had contracted the last known "wild" case of smallpox in the world.

Today, the pestilence is back in the "bottle"— those bottles being the carefully guarded property of the United States and Russia (and possibly, illicitly, various unstable regimes as well). Several years ago, after serious scientific and ethical debate, the World Health Organization (WHO) decided that the remaining known stockpiles of the virus—those held by the United States and Russia—should be destroyed. A date for that action was agreed upon, but when the time came the destruction was postponed.

The clock was reset twice again, most recently to late in 2002. But in light of post- September 11 apprehension about bioterrorism— and the possible need for some supplies of the virus for research and vaccine-development purposes—WHO has recommended a postponement of the destruction yet again.

And so this patient microbe—perhaps the most lethal of what biologist Paul Ewald, Ph.D., calls "sit-and-wait pathogens"—is still among us.

How this story about President Wheelock & smallpox came to be written

The adjacent story is set primarily in 1776, but I hope you will pardon a digression here to 1940, on a late-winter evening a few months before my graduation from Dartmouth College.

There were 30 or 40 of us—the seniors taking American literature courses, plus a few of our professors—crowded into the study room in Dartmouth's Sanborn Library. It was a bitter-cold night, and the wind was howling. But inside Sanborn, a familiar gravelly voice rose above the gusts: Robert Frost was reading his own poetry from a comfortable chair by a birch-log fire. "History," he said, "is the grand total of a hopsack full of elusive, bright little facts that join one another down the years to make a story— or a poem, don't you see. Listen, it's sort of like this . . ." And he proceeded to read "A Hillside Thaw."

If I close my eyes, I can still hear his words about a tentative February sun that melts the winter drifts and releases "ten million silver lizards out of snow"—lots of little rivulets, each of them small individually but significant collectively as they run one into another.

|

|

This reading with Robert Frost, in the very setting author Seymour

Wheelock describes, dates from 1947—a few years after he heard Frost. |

As an example of Frost's imagery, take the subject of the accompanying article. My interest in the topic began when I received a letter from a gentleman in Westborough, Mass., who was in the early stages of forming a Revolutionary War reenactment group. He had named it the Colonel Moses Wheelock Regiment of Muskets and wondered if I had any information on the group's eponym.

The colonel was a first cousin of the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock, Dartmouth College's founder and first president, as well as a direct ancestor of mine. I was therefore able to add some of Frost's "elusive, bright little facts"—the "silver lizards" of his poem—to the store of facts that the Massachusetts gentleman already had. And, fortuitously, he was able to add a few to mine, for in return he sent me a copy of a letter that General Washington had written in 1781 to John Wheelock, who had succeeded his father as Dartmouth College's president:

Headquarters, New Windsor, June 9, 1781

Sir:

I have received your favor of the 25th of May, and have paid due attention to the business recommended therein.

Pleased with the specimen you have given in Mr. Vincent of the improvement and cultivation which are derived from an education in your Seminary of Literature, I cannot but hope the Institution will become more flourishing and extensively useful.

With due respect, etc.

Geo. Washington

Who, I wondered, was Mr. Vincent? He was clearly a worthy scholar in Washington's estimation, but I had never heard his name despite my familiarity with Dartmouth's history.

Soon enough I found the answer in the yellowing pages of George Chapman's Sketches of the Alumni of Dartmouth College, under the Class of 1781: "Louis Vincent was born at Lorette, near Quebec, E.C., and died there in May 1825, at age 65. He was a Lorette Indian, who after graduating returned to his tribe and was long a very useful teacher among them. While in college, he was the happy instrument of saving, by his alertness and skill, Amy, the child of Dr. Laban Gates, who was near perishing at the bottom of a well."

Louis Vincent, it turned out, was a Huron from the easternmost of several villages established in Canada by the Jesuits for Christianized members of the Iroquois and Huron nations. Lorette stood at the falls of the St. Charles River, only eight miles from Quebec, and Vincent returned there from "the college on the hill." But before he left Hanover, he made himself a local hero by rescuing young Amy Gates from her soggy fate and restoring her to the agitated bosom of her father, Dr. Laban Gates.

According to historian John K. Lord, Dr. Gates was an authentic eccentric "and difficult to live with." Evidence for this assertion exists in a broadside titled "Partnership Dissolved," in which he feverishly warns all and sundry not to trust his wife.

Dr. Gates had a wooden leg, and rumor had it that on a dare from a stranger he plunged his ligneous foot (still bearing its shoe) into a bucket of boiling water in order to demonstrate his superior powers of resistance. Sadly, that story is possibly untrue.

The adjacent story, however, is quite true. It contains lots of Frost's "silver lizards"—tidbits that, like his rivulets, are small in and of themselves but significant collectively. Let us only hope that smallpox—a highly infectious disease so virulent that it killed up to 40 percent of its victims—remains but a rivulet.

Seymour E. Wheelock, M.D.

Seymour Wheelock—who has a relative in common with Eleazar Wheelock, the founder and first president of Dartmouth College— graduated from Dartmouth in 1940, was on the housestaff at Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital in 1944 and 1945 (after graduating from Northwestern Medical School), and was a member of the Hitchcock Clinic pediatrics staff from 1962 to 1966. He is now a professor emeritus of clinical pediatrics at the University of Colorado and writes regularly about various aspects of medical history. His previous features for Dartmouth Medicine have included one about DMS alumni who served in the Civil War and one concerning a surgical feat performed by DMS's founder, Nathan Smith. Some punctuation and capitalization in the historical quotations in this article have been modernized for ease of comprehension, but all original spellings have been retained.