So, you want to be a doctor?

By Laura Stephenson Carter

All Photographs: J.D. Denham

The decision to go into medicine should not be made lightly, given the years of training and the financial burden involved. Yet how do premeds find out if medicine is really what they envision it to be? Dartmouth undergrads are getting a better view of the profession than ever, thanks to the DMS faculty.

|

|

Lee Witters, right, an endocrinologist on the DMS faculty, is spending a good deal of time with Dartmouth undergrads of late, in his role as advisor to the Nathan Smith Premedical Society. Pictured with him are several seniors active in the Society—from the left, Amanda Venti, Alexei Wedmid, Melissa Kazanowski, Angela Poppe, and Jennifer Platt. |

A child was having severe seizures, and its head was very small," says Jennifer Platt, a Dartmouth College senior, about a premature baby in Dartmouth- Hitchcock Medical Center's intensive care nursery. "I was very conscious of how everyone rushed in and took care of the child and how they took care of the mother at the same time. It was very intense for her to suddenly see so many people coming in and having this big emergency going on with this newborn child, and for her not to know how to handle it at the same time. I was very concerned not just for the child but also whether [the mother] had the support network she needed to cope with the situation."

Platt, a biology major at Dartmouth College and president of the female a cappella group, the Decibelles, had her heart set on a career in medicine as early as high school. But only recently has she begun to truly comprehend what practicing medicine is all about. Through the Nathan Smith Society, the Dartmouth premed organization, she has volunteered in the DHMC Emergency Department, heard Dartmouth Medical School students talk about getting into medical school, listened to career advice from DMS alumni, and shadowed a DHMC pediatrician—Carole Stashwick, M.D.

"I think what I learned the most working in pediatrics [is] that doctors need to take care of both parents and the children," Platt says.

Many Dartmouth undergraduates are getting an inside look at what it's really like to be a doctor, thanks to the Nathan Smith Society, founded in 1976 and resurrected just two years ago by DMS endocrinologist Lee Witters, M.D. Students have been shadowing doctors, meeting with DMS students and alumni, and, in general, getting a closer look at the medical profession.

"What we really try to do in the Nathan Smith Society," says Witters, "is to put that extracurricular dimension on the premedical experience at Dartmouth. The curricular dimension is pretty well set. It's the extracurricular dimension, whether it's experiential things like shadowing, volunteerism, and community service, research experiences, or helping them find off-term or leave-term opportunities, that allows them to see the broader world of medicine."

|

|

The classroom aspect of Jennifer Platt's premed experience at Dartmouth has been complemented by her ability to shadow a DMS pediatrician. |

"I can see whether medicine is really for me," agrees John Brandsema, a sophomore. "If I have this concept of the ER [as being] somebody coming through the sliding doors every three seconds with some huge emergency and drama, that's not realistic." Although Brandsema has wanted to be a doctor since he was three years old, he doesn't yet know what kind of doctor. His shadowing experiences may help him decide.

He liked the idea of sports medicine, so during his first semester at Dartmouth he spent three hours every Friday shadowing Kristine Karlson, M.D., a family physician with additional training in sports medicine who practices at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Community Health Center in Hanover. "She turned out to be more of a general practitioner-family physician. Maybe I saw two people with actual sports injuries while I was there. It still ended up being a good experience because now I know that [family medicine is] something I'm not really that interested in."

Second semester, Brandsema shadowed radiologist Brian Szymanski, M.D., a fellow in cross-sectional imaging. "I got to see all the different areas of radiology. He was very good about telling me why he was making certain diagnoses. I learned a lot. He was very also very enthusiastic about the subject. You are sort of the brain and epicenter of the hospital there. It's a very exciting place to be. I don't know—that might be an area I might be interested in later."

|

Brandsema has also shadowed orthopedic surgeon Charlie Carr, M.D., the team physician for Dartmouth's athletic teams. He thought watching an operation was interesting, but admits, "I don't know if I could ever be a surgeon; I have trouble drawing a straight line."

"Shadowing was part of the original [Nathan Smith] Society," says Witters, who is not sure why or when that initiative disappeared from the group's offerings. "I do know that in the early '90s [shadowing] became a very disorganized program and there really wasn't any central leadership or coordination. It was very hit or miss. More importantly, and this is one of the reasons the Hospital got down on it, it didn't offer the students any guidance on how to be prepared for it, what kinds of things they should be thinking about."

"Kids had the wrong view of it; [they] came as voyeurs. Physicians cooled," agrees vascular surgeon Dan Walsh, M.D., who is now an enthusiastic supporter of the shadowing program. "Lee Witters revitalized it, and did it in just the right way. [He] makes sure the kids understand the physician-patient relationship; this is a very private, very important thing and you need to treat it as such. Now the kids have shown up very well dressed, very serious, very professional."

"The students have to sign a waiver of confi- dentiality, go to an orientation, or view a videotape," explains Witters. "We spend a lot of time talking about patient confidentiality, the professional code of conduct, and they get and have to read the DHMC code of professional conduct. They all get badges, which is state law now. They have to have TB skin tests. If they go into the operating room, they have to meet OSHA requirements."

The students appreciate the opportunity to see surgeons in action. Dartmouth senior Alexei Wedmid, outfitted in green scrubs, a mask, and OR booties, would stand on a stool above the "ether screen," at the head of the surgery table, so he could observe cardiothoracic surgeon John Sanders, M.D., doing open-heart surgery. "People were very serious, but they did a lot to make everyone in the room seem comfortable. I could see them opening it up, stitching it up, and doing everything in between. They had to stop it [the heart] and reroute [the blood]. Even though it was such an important matter, they weren't stressing themselves to the point that it would be a painful life to live. I would think that open-heart surgery would be such a traumatic thing, that I would be scared. But they made themselves and me seem very comfortable. Wow!"

|

|

Drs. Walsh and Sanders both grew up in medical families, where it was routine for children to accompany their physicianparents to the operating room and even to patient bedsides. "I went to my first patient's bedside when I was five years old," says Walsh, whose father was a cardiologist and mother was a medical secretary. So far only one of the students who has shadowed him was from a medical family.

The doctors try to make the experience interesting and informative for students. "We try to pick an operation that's something they might be able to see," says Sanders. "Some of what we do, the surgeon can see but nobody else can. The majority of them find it fascinating. One of the things about surgery is that it's a pretty good bringing together of anatomy and physiology, chemistry, pharmacology. All those disciplines unite in the operating room. You can see the utility of some of the stuff you labor over to learn. I think that's valuable."

Students may be awed by surgery, but they are also impressed by the other aspects of medicine. Scott Warden, who graduated from Dartmouth in 1999 and is now at Harvard Medical School, shadowed orthopedic surgeon Michael Mayor, M.D.

"He was fantastic because he always spent the time to explain things. Before we'd see a patient, he'd show me the x-rays and go over what the problem is and what they're working on," says Warden. "It was neat to see the real patient-doctor interaction. I was there for a couple of months so I'd see the whole process. The patient would come in and I saw some surgery—like a hip-replacement surgery and a knee-replacement surgery. I was allowed into the OR, right beside Dr. Mayor. He was pointing things out even during the procedure. I saw all the different facets—outpatient, the actual operation, and afterwards."

|

|

Alexei Wedmid was impressed by the OR atmosphere when he observed open-heart surgery at DHMC. |

Warden enjoyed another aspect of shadowing Mayor. "There's also something to be said for a doctor who's really happy with what he's doing," he adds. "You hear so much now how medicine's changed with insurance and how it's not the same as it used to be, and many doctors are disappointed with the change. It was nice to see Dr. Mayor, who's so enthusiastic about what he does. It was encouraging to see that there are really happy doctors out there."

Brandsema agrees. "I was just amazed by how much the people that I followed loved their job. They have fun; they love what they do. That's given me real hope, too, because when I'm sitting in one of those intro premed courses with 180 other people who are all driving to the same goal that I am, it can get very frustrating. But I hold on to how I feel when I'm following one of those doctors in the hospital."

Dartmouth senior Melissa Kazanowski, a biochemistry major and art history minor, has explored medical research opportunities as well as clinical ones. While she learned a lot by shadowing anesthesiologist Carter Dodge, M.D., she also observed autopsies being performed as part of her independent research project in the pathology department.

"I never realized how beautiful the human body is," she says. "The colors are so brilliant. It's really incredible. How the body works from the inside I thought was fascinating."

Kazanowski describes one unforgettable incident. "We were dissecting brains. The preceptor said we have to go downstairs and pick up a brain, so I was following behind him. He opens up a door and here's a man who'd just had a heart attack. He was my father's age, which was a little disturbing. He was slit from his chin down to his groin, his head falling back. This was definitely startling. I didn't realize we were taking the brain out of his cranium."

The students also seek other chances to gain medical experience. Kazanowski trained as a wilderness EMT so she could work on the ski patrol at the Dartmouth Skiway. She and Wedmid participated in the Koop Institute's ArtCare Program, which focuses on healing through art; Kazanowski worked with children with cancer, while Wedmid volunteered at the DHMC Child Care Center. Platt volunteered in the DHMC Emergency Department one term. Brandsema, a Canadian resident, worked as a recreational therapist in a hospital psychiatric ward in Saskatchewan. And Warden worked in the emergency room at a local hospital while he was an undergraduate.

|

|

When students can spend an entire term working in a medical setting, all day, every day, they get an even better idea of what the practice of medicine is all about. Kazanowski worked in the cardiology department at Columbia-Presbyterian in New York City one whole summer.

"I thought it was a really good introduction as to what this type of doctor does," Kazanowski says. "As far as really understanding the lifestyle of a doctor, and the everyday work of a doctor, I think you have to do something during your off-term, and kind of live it."

She found a summer position through the Dartmouth Career Services Office with Dartmouth alumnus Shunichi Homma, M.D., DC '77, director of the echocardiography laboratories at Columbia- Presbyterian. "I looked up all the doctors who were affiliated with medical schools in Manhattan and wrote about 15 or 16 letters explaining what my past experiences were, what I wanted to do in the future, asked if they had any advice, and I sent along my resume. . . . Out of the 15 letters I sent out, I received 13 job offers. It was incredible!"

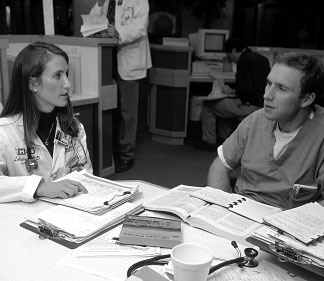

|

|

Lara Belana, left, now a first-year pediatrics resident at DHMC, agrees that having a chance to see medicine firsthand is key for premeds. |

Dr. Homma "was so nice to me, giving me a great experience as far as seeing anything I could possibly want to see. Learning about different diseases was fascinating," as was "how to control diseases, the politics of a hospital, how a doctor operates, what his lifestyle was like, how you deal with patients and their fears and their concerns. All of these patients were older," she adds. "Most were from the Dominican Republic or Russia and didn't speak English at all and were afraid of taking medicine and afraid of surgery. The doctors had to convince them that they really were doing a good job. I think that was a whole different side of medicine."

"Melissa was a phenomenal student and we all enjoyed having her with us," says Homma.

While Dartmouth students who graduated before the Nathan Smith Society was revived may not have participated in the shadowing program at Dartmouth-Hitchcock, many of them, like Lara Belena (DC '95 and Tufts Medical School '99), found other ways to get medical experience. Belena, who is now a first-year pediatric resident at DHMC, worked at Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y., during two of her off-terms. "I got to see a lot of medicine firsthand, a lot of strokes, a lot of neurological disabilities," she recalls.

Belena, who majored in music and came to Dartmouth to study with pianist-in-residence Sally Pinkas, took all the required premed courses as an undergraduate. "But I wasn't thrilled about biology class or organic chemistry. I never, ever, ever, ever want to repeat that—never. I think that's very different than being a practicing physician."

|

|

Dartmouth encourages undergrads to explore many academic interests. "That's the beauty of Dartmouth. It's a wonderful liberal arts college," says Belena. "They really did give you the opportunity to study science and study it at a high level— enough to get you into a great medical school. Yet you could focus on the arts, you could focus on drawing, or art history. In my case I focused on music, which was a huge part of my life from second grade on."

Belena continues, "It speaks highly of Dartmouth that you don't have to be so engrossed in medicine as an undergraduate. Dartmouth is a place where they really foster the liberal arts education. It's the four years of your life where you can just study and learn for your own benefit. It's a once-ina- lifetime chance."

But even though undergraduates enjoy the ability to explore a variety of disciplines, they are looking for career guidance, too. The Career Services office offers that kind of advice for all students, including those interested in medicine. And now the Nathan Smith Society, with the help of many faculty at DMS, is augmenting what's available for premeds with a plethora of advice and insights and learning opportunities.

"The Nathan Smith Society has really focused me in my pursuit of a career in medicine" says Platt. "I came in freshman year with a vague idea that I wanted to be premed, tentatively followed the path, and didn't really settle into it until I was contacted by the Nathan Smith Society. And that pulled it all together for me."

She pauses, then smiles: "I found myself through the Nathan Smith Society."

About the Nathan Smith Society

The Nathan Smith Premedical Society serves undergraduates at Dartmouth College with career interests in the health professions. (The current Nathan Smith Society bears no connection to an earlier group bearing the same name—a DMS alumni organization that existed prior to 1970.)

The Nathan Smith Society's Web site

(www.dartmouth.edu/~nss/) is a repository of

information for premeds, including news on

Society activities; the physician shadowing

program; volunteer, research, and internship

opportunities; curriculum planning; the medical

school application process; and taking

the MCAT (Medical College Admission

Test). It also contains links to other medical

Web sites. In addition, there is a Q&A page,

and answers to "Frequently Asked Questions"

are displayed. A few sample pages are

reproduced at right.

The Nathan Smith Society's Web site

(www.dartmouth.edu/~nss/) is a repository of

information for premeds, including news on

Society activities; the physician shadowing

program; volunteer, research, and internship

opportunities; curriculum planning; the medical

school application process; and taking

the MCAT (Medical College Admission

Test). It also contains links to other medical

Web sites. In addition, there is a Q&A page,

and answers to "Frequently Asked Questions"

are displayed. A few sample pages are

reproduced at right.

"This is a student society," explains its advisor, Lee Witters. "This is not a program that the College or Medical School has established and is looking for membership from the students. I very, very much rely on a very talented and involved group of undergraduates to create programs, to create ideas, to do the spadework necessary to make this a useful organization. I see myself as a facilitator, someone who can open doors and provide resources. But it's really their ideas and their energy that have created this society."

Witters's role in the revitalization of the organization is not just incidental, however. In 1998, he was named "Faculty Advisor of the Year" by the Dartmouth Council on Student Organizations. He was selected for the honor from among the advisors of over 250 undergraduate groups, after just one year of advising the Nathan Smith Society.

"People ask why is this named after Nathan Smith," he says. "He was the founder of Dartmouth Medical School."

But, he adds, "when Dartmouth Medical School was founded by Nathan Smith in 1797, the courses were part of the College. . . . Although the School was created in name, it didn't really exist physically. Nathan Smith was really part of the College and College faculty. I think it's quite appropriate that the Society be called the Nathan Smith Society for that reason."

Laura Carter is the newly named associate editor of Dartmouth Medicine. This is not her first feature for the magazine, however; she wrote as a freelancer about Dartmouth astronaut Jay Buckey's flight on the May 1998 Neurolab mission in the Fall '98 issue. She has also contributed a number of stories to other sections of the magazine. For more on her background in science and medical writing, see the "Editor's Note" on page 2 of this issue.