Faculty Focus

Peter Silberfarb: A partisan for psychiatry

By Megan McAndrew Cooper

Why don't you write up my dog, instead?" Peter Silberfarb asks, not entirely joking. He's that kind of person. But as handsome as his Gordon setter, Deirdre, is, she's no match for Silberfarb's accomplishments.

The Raymond Sobel Professor of Psychiatry, Peter Silberfarb, M.D., has been on Dartmouth's faculty since 1972, when he served as chief resident in psychiatry. He became acting chair of the department in 1984 and has been its chair since 1986. The first psychiatrist in the United States hired to work full-time for a cancer center (in 1974), Silberfarb has two principal interests: the emotional effects of cancer and its treatment, and the rigorous testing of doctors who want board certification in psychiatry.

Prevailed upon to describe his career rather than his dog, Silberfarb recalls that he came to Dartmouth as a resident in medicine in 1966, then became one of the institution's first psychiatry residents—and has never found reason to leave either the institution or the discipline.

He became "fascinated" as a medical resident, Silberfarb says, by "the interface between cancer and psychiatry" when he was on a rotation in oncology. "People with cancer are perceived to have terrible psychological problems," he says, "but they are, in fact, very stoic generally and don't have excessive psychological issues. They're well-adjusted, and they're coping." What Silberfarb noticed, though, was that there was "subtle cognitive impairment —in memory and thinking—in patients on chemotherapy." These impairments, he observed, are often reversible, but they can present a substantial burden for patients and their families. He first wrote about the phenomenon in the American Journal of Psychiatry in the 1970s, but he notes that the subject has not gotten a lot of attention until the last five years.

In the meantime, Silberfarb became interested in trying to identify the cause of these cognitive problems. He and colleagues Tim Ahles, Ph.D., and Andrew Saykin, Ph.D., are now in the process of seeking funding to do brain-imaging studies in cancer patients who are on chemotherapy, in an effort to pinpoint the sources of any cognitive deficits they are experiencing.

Although he now does little clinical work, Silberfarb remains interested in caring for patients with severe psychiatric illnesses and those who have cancer. "The tenets of care are simple things," he says. "Patients want to be comfortable; they want someone to listen to their story; they want relief from anxiety and depression. Unfortunately, those are the things that usually are forgotten."

Not only are cancer patients anxious and depressed, but delirium is a serious problem for those with mental impairments from chemotherapy or pain medications. "There are substantial quality-oflife issues as well," he notes, which need both medical and psychiatric support. Insomnia, depression, and pain are all important side effects, and it can be difficult to sort out the differences between depression and the side effects of cancer.

"Sometimes patients are more interested in functional status than cure," he notes. "We'd all like to be cured, but most patients are more interested in what they can and can't do, and in the control of their symptoms, than anything else." This is logical, he points out, for patients who have little control over their treatment. For example, patients who are having radiation therapy "can do little to treat their own illness—things are done by others. This is different from other illnesses, like heart disease and diabetes, where you can do things for yourself to change the outcome. Cancer is one disease in which you have little control, which undermines your sense of mastery." Paying attention to emotional illnesses that are associated with such loss of power and control can improve patients' well-being, Silberfarb explains, even if it can't change their clinical outcomes.

|

Psychiatry, Silberfarb feels, is "a wonderful field—and more rewarding now that science is helping us understand how the mind works." He had an early interest in psychiatry, he says, but at the time he began his medical education the field was highly analytical, "since there wasn't much else to do for psychiatric patients." While he was a medical student, he became disenchanted with psychiatry because he felt it "wasn't that helpful to the seriously mentally ill." So he decided to enter internal medicine instead.

It was Silberfarb's mentor at Dartmouth, Robert Weiss, M.D., then chair of psychiatry—along with advances in psychiatric treatments just then emerging—that changed his mind. Silberfarb's interest was piqued during a two-month rotation in psychiatry, and he soon joined the nascent psychiatry residency, turning down the chance to be chief resident in medicine. "When I switched," he remembers, "people [said], 'You're throwing away a brilliant career.' Most of my colleagues were upset."

Silberfarb's promise was soon just as evident in psychiatry. After a brief detour, that is. Before he returned to Dartmouth, he served a stint as a lieutenant commander in the Public Health Service, in the epidemiology branch of the Centers for Disease Control, where he published five papers on fungal diseases. "It was quite a background for psychiatry," he says, laughing.

Since then, he's compiled an impressive CV. He is past president of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology; past president of the American Association of Chairmen of Departments of Psychiatry; and past chair of the National Psychiatry Match Review Board. He has served on the governing council of the American Psychosomatic Society; on the executive committee of the American Board of Medical Specialties; on the Psychiatry Residency Review Committee of the American Council of Graduate Medical Education; and as a consultant to the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry, the World Health Organization, and the National Cancer Institute's board of scientific counselors. And he is currently a director of the American Board of Family Practice and serves on the editorial boards of four journals.

Integrating psychiatry with oncology has been easier at Dartmouth, Silberfarb believes, because there's a longstanding relationship between the departments. "[Oncologist] Herb Maurer and I were residents together," he says, "so if I go over there, they're very accepting." Before he became so involved in national activities, Silberfarb remembers, he would go on rounds with the oncology team, providing "help for patients as well as the housestaff." The lesson, he says, is "not to get too involved, but involved enough." This includes giving up preconceived notions and illusions of "doctor knows best," among other things. Silberfarb says that "patients want to tell the doctor what's on their minds, and the doctors think that they know what the patient needs." That's not usually the case, he observes: "Every time I've thought I've known what a patient fears before I've talked to them, I've been wrong."

Focusing on patients' stories offers several benefits, Silberfarb believes. First, it can help them overcome the powerlessness often brought on by cancer treatment. And hearing what patients fear can help doctors figure out how to better treat the things their patients worry about. "What patients fear most of all is losing control," he says. "Of their bodily functions and of everything else. They also fear that they will not be able to fulfill their obligations to others."

|

|

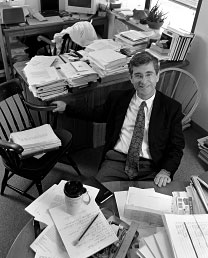

The piles of paper in Peter Silberfarb's office testify to his national prominence in psychiatry and the demands of chairing a large department—the smile, to his love of the discipline. Photo by Jon Gilbert Fox |

What can doctors do to make a difference in the face of such concerns? "You'll never find out unless you listen," Silberfarb says, "and listening doesn't take a lot of time, for a good doctor. You don't have to spend a lot of time, but you have to spend time being totally focused on the person." The key to being a good therapist is understanding what the patient wants you to listen to and wants to be reassured about. Many patients, he asserts, "are not looking for anything but reassurance that they'll be okay in our hands, that we'll take care of them."

Protecting the public trust in psychiatry is, for Silberfarb, part of the mission of his work in graduate medical education —which has included chairing the organization that screens candidates for board certification in the field.

"Good intentions aren't enough," he says. "We all have good intentions." The psychiatry board examiners, he explains, must look for communication skills, good interactions with patients, and the ability to follow the patient's lead—"plus they have to know how to treat." The reviewers must agree on one thing, Silberfarb adds: "Would I want this person caring for someone in my family?"

"It's hard being a doctor," he admits. "It's a major responsibility—you can't get any more responsible than we are—yet we are not able to do what we think is best in every case, because of the way medicine is structured now. There's a whole new bureaucracy that's parallel to medicine, and it means you spend too much time on the phone, battling payers." He is, momentarily, depressed by that thought.

But then he brightens: "It's been very rewarding being here. I've been able to do a lot of different things—service, clinical work, education, research, and now I'm more involved in national things, the administration of national organizations. And I've been able to stay right here while I did it all; I never had to go anywhere else."

Clearly, Silberfarb's decision to switch to psychiatry 30 years ago would, could she comprehend it, set Deirdre the Gordon setter's tail to wagging.

Megan Cooper is the editor of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care and a freelance writer. She writes regularly for Dartmouth Medicine, among other publications, and also contributed an essay to the feature in this issue that begins on page 28.