Drama on Denali

By John Morton

When DMS faculty member Dudley Weider set out to climb North America's highest peak, it was supposed to be an adventurous vacation. But the expedition took a harrowing turn when Weider was called on to save the lives of several fellow climbers.

|

|

| |

|

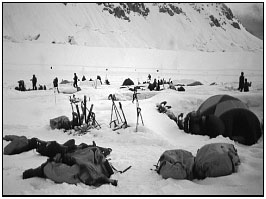

Clockwise from top left, a climber perched atop a rock formation known as the "End of the World"; the camp at 7,800 feet; an expanse called "Windy Corner". | |

Dudley, you're a doctor aren't you?" The question came from Chris Morris, the leader of Dudley Weider's 12-member expedition on 20,320-foot Mount McKinley—more commonly known today by its Native Alaskan name, Denali. Totally exhausted from eight hours of "post-holing"—crashing every few steps through the snow's soft crust, under the weight of a 60- pound pack—Weider had just staggered with his team into Denali's 14,200-foot camp. It was mid-June of 1998, and the team had spent five days ferrying food and supplies up from the Kahiltna Glacier, more than 7,000 feet below.

"Yes, I'm a doctor," Weider managed to gasp between deep gulps of the thin air. "What's the problem?"

"Would you follow me?" the guide asked urgently. The National Park Service maintains a medical tent at 14,200 feet to care for the 1,300 climbers a year who face frostbite, exhaustion, and death in their effort to conquer North America's highest peak. Doctors and medics from throughout Alaska and the western United States volunteer their time for three-week rotations during the mountaineering season, but the Anchorage physician who had been scheduled to be on duty had slipped a disk in his back and thus hadn't been able to make the climb. Scott Darsney from Dutch Harbor, Alaska, an experienced climber and qualified medic, had his hands full in the first-aid tent, and he wanted the reassurance of a physician.

|

|

|

The rescue helicopter; the medical tent at 14,200 feet. | |

Although Dudley Weider is no stranger to ultra-endurance expeditions in hostile environments, his first days on Denali had not been pleasant. An otolaryngologist who's been on the Dartmouth faculty since 1974, he had trained diligently in the months prior to the climb by mowing his lawn under the weight of a 60-pound backpack; attending technical mountaineering courses in North Conway, N.H.; and wearing his heavy, plastic-shelled climbing boots at every opportunity. But there was no way Weider could have prepared for the jet lag, the altitude, and the mind-numbing fatigue of repeated treks hauling supplies from the Kahiltna Glacier, where bush planes on skis deposit climbers, to high on the shoulder of the majestic peak.

The 12-member expedition—of which, at age 59, Weider was the oldest member—had been grounded in the village of Talkeetna for four days by bad weather. When the skies finally cleared and the ski planes were able to deliver the group to Kahiltna, all of them were eager to start climbing. Taking advantage of Alaska's famous midnight sun, the team left the glacier airstrip at midnight, each climber staggering under the weight of a 60-pound pack and pulling another 40 pounds of supplies in a plastic sled.

They arrived at the 7,800-foot elevation, a distance of four and a half miles over the ground and nearly 1,000 feet above the glacier landing strip, by 8:00 the following morning. After establishing camp and having a bite to eat, they collapsed in their tents to sleep through the day. On the mountain's lower slopes, the deep snow is often soft during warm summer days, so climbers frequently move up the mountain during the twilight of Alaskan nights, when the frozen crust is more likely to support their weight.

| |

|

|

|

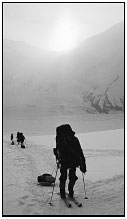

An ascent of Denali starts with a flight in a three-passenger plane (above) from the village of Talkeetna into the base camp on Kahiltna Glacier (top). From there on, the climbers move up the mountain one step at a time—each member of the team carrying a 60-pound pack and hauling a sled holding another 40 pounds of supplies (upper right). When they make camp, it's in tiny, two-person tents, roped together for protection from the wind (lower right). | |

During their second evening on the mountain, the group took half their gear from 7,800 feet to 9,800 feet and cached it before returning to the lower camp to rest. The following day they broke camp at 7,800 feet and ferried the remaining supplies to 9,800 feet. Once a camp was established at that height, the expedition began hauling supplies to 11,000 feet, and then leapfrogged on up to 13,500.

Although his first days on the mountain had been torture, and Weider was cursing himself for inadequate training, by the fourth day he was starting to feel better. Paradoxically, however, a couple of his younger teammates were beginning to suffer from the high altitude. When the expedition reached the 14,200-foot camp at 11:00 p.m. that night, Weider was exhausted by the day's climb, but he had overcome earlier misgivings about his ability to reach the summit.

That was the point at which Chris Morris showed up in Weider's tent. Nearly asleep on his feet, Weider followed his expedition leader to the medical tent, where he found a 60-year-old man with a history of angina who was suffering from acute chest pains. The climber's electrocardiogram was clearly abnormal and two sublingual doses of nitroglycerin seemed to have little effect. In spite of the patient's desire to continue his climb, Weider recommended a helicopter evacuation and eventually convinced him to accept a chopper ride off the mountain. It was 1:30 a.m. when the exhausted doctor finally stumbled back to his tent for the night.

Dudley Weider has had a lifelong fascination with remote locations and severe winter weather. As a child growing up in Cleveland, he remembers being so captivated by Admiral Byrd's film describing Little America, the research station on Antarctica, that he phoned home from the theater for permission to stay and see the movie a second time. While at Bay Village High School, Weider played football in the fall, but his primary sports interest was speed-skating, at which he eventually earned national ranking as a junior.

When Weider began to consider colleges, Dartmouth quickly became his top choice. Not only was Hanover a rural location blessed with relatively severe winters, but Baker Library housed the Stefansson Collection, the world's most comprehensive assortment of books, articles, and artifacts on the Arctic—with the exception only of a similar collection in Moscow. Vilhjalmur Stefansson was an Icelandicborn, Canadian-American anthropologist and adventurer, who early in the 20th century made several expeditions to the Arctic. Stefansson was one of a very few explorers to learn the Upik language, which he did by speaking with Inuit children in Barrow, Alaska. Weider was fascinated by Stefansson, so Dartmouth was a logical choice.

"Drama on Denali" continued. . .