At last . . .

By Mary Daubenspeck

Illustrations: John Bolesky / Artville

Palliative care—the care of patients for whom curative treatment is no longer an option—is receiving increased attention nationwide, including at DHMC.

There was nothing lucky about my sister-in-law's experience with pancreatic cancer—unless it was having my brother, Andy, so near by throughout it. A research physiologist based at DHMC, Andy was able to be at Sarah's side for every appointment, every diagnostic and surgical intervention, every chemotherapy infusion, every hospitalization.

During those stressful and often disheartening months, Andy could be relied upon to ask all the right questions and to remember all the answers in order to explain to Sarah and the rest of us—as often as necessary —the complexities of her treatment and its desired and undesired effects. As a member of the DMS faculty, he shared with Sarah the comfort of knowing as friends and colleagues many of the people who treated her. As an engineer, he was clever enough to design a matrix of all her many medications (at times as many as 15), printing it out and organizing each day's doses in a plastic fishing-tackle box.

"How few cancer patients have an Andy to go through this with," I mused many times during that seemingly endless, but now all-too-short period. "What if one is alone in the world when one receives a diagnosis like this? What if one is poor? How daunting it must be to make treatment decisions all by one's self, including the achingly difficult last ones about when to admit defeat and where to die."

Seeking a better way

In America, death is rarely unexpected, coming as it now usually does at the end of a chronic, progressive illness. But for all its predictability, it is often handled in crisis, with little understanding of the process or of the possibilities for easing a loved one's pain and a family's grief.

The question of how to better minister to the dying has been before us since 1969, when psychiatrist Elisabeth Kubler-Ross's book On Death and Dying became a best-seller. Within five years, Americans began to embrace the hospice concept, which Dame Cicely Saunders had introduced in England in 1967. Recently, however, the public debate about dying has been polarized by Michigan physician Jack Kevorkian's administration of lethal chemical cocktails to patients with incurable diseases. But just before Kevorkian's most recent trial in March of 1998, the Last Acts Coalition—a national group of experts in end-of-life care—announced the results of a survey of 1,007 Americans. The survey had asked how we should deal with the problem of end-of-life pain and suffering. Despite previous polls' demonstration of strong support for Kevorkian's cause, this time respondents chose improving care of the dying over legalizing assisted suicide by a margin of three to one.

Clearly there is a better way. Its name is "palliative care" (from the Greek root pallios, meaning cloak, in the sense of a comforting mantle). The World Health Organization has defined the concept as care that affirms life and regards dying as a normal process. It neither hastens nor postpones death; it provides relief from pain and suffering; it integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of care; and it proceeds in accordance with the patient's wishes.

"The Kevorkian debate raises important questions, but leads to the wrong answers," says Ira Byock, M.D., director of a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant program called Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care, which has funded a major palliative-care initiative at Dartmouth. "The debate addresses people's many fears about terminal illness," adds Byock, "but Americans should expect —and be able to get—end-of-life care that respects their own wishes and needs."

Facing the fear

In most developed countries, patients with chronic, progressive illnesses spend their last days in hospitals and institutions, where, it is assumed, more can be done for them. Consequently, few young people have ever seen anyone die, a fact that surely compounds fearfulness. Yet as the American population ages, and increasing numbers of babyboomers wrestle with the knotty problems of caring for their elderly parents, more and more of them are seeking knowledge about what to expect at the end of life—their parents' and their own.

In the winter of 1996, Sarah Goodlin, M.D., then an associate professor of medicine at DMS and a leader in the effort to improve care of the dying at DHMC and to introduce palliative care into the DMS curriculum—worked with New Hampshire Hospices to organize a series of focus groups. She wanted to learn from family members of people who had recently died, and from those living with a terminal illness, what was important to them during the period near the end of life.

"What we heard," says Goodlin, "was that patients and families want honest prognostication, clear information about what to expect, and guidance from health-care providers. People want control over their lives, and they need support with emotional issues and with spiritual issues that confront them at the end of life. They also need help with care, and they want to maintain independence."

|

|

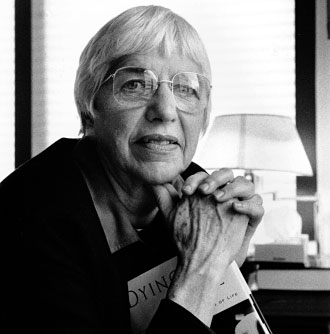

Hospice Director Marie Kirn believes in empowering patients to make their own choices about dying. |

If so, palliative care's time has surely come. Unfortunately, in America it is neither comprehensive nor widely accessible. Says Goodlin, "The [end-oflife] experiences people described were tremendously variable: some had a relatively peaceful experience, and others were completely unaware of resources available to support them."

In the 1998 Last Acts Coalition survey, people were asked to rate how the current system cares for dying patients. Very few said it does an excellent job, and about half believed it does a fair or poor job in helping patients to remain pain-free (46%), to determine their own care (48%), and to retain their dignity (54%). Most (79%) believed the medical system does only a fair or poor job of ensuring that families' savings are not wiped out by the costs of end-of-life care.

Reform proponents are working hard to get the message out that Americans have not only a right to comprehensive palliative care, but also a responsibility to demand it.

But there are entrenched barriers: Today's health-care professionals aren't uniformly trained in palliative-care techniques such as pain- and symptom-management. They are hobbled by antiquated regulations that limit their ability to prescribe narcotic pain relievers. Health insurance plans are less than helpful as well, reimbursing patients unequally for in-hospital and out-of-hospital care. And, of course, there is our culture's deathdenying nature.

With the explosion in health-care technology and innovative medical treatments, physicians are more capable than ever of prolonging life and postponing death. While many people have benefited as a result, these advances have raised complex new questions that have no easy, obvious answers. Today, when so much can be done, sometimes we beg the ethical question of what should be done.

Says Goodlin, "Medical care has focused on keeping people alive, and it has been so successful that we have difficulty identifying people as dying." To those whose goal has been defined as curing illness, the death of a patient may represent a personal defeat.

Yet Marie Kirn, the director of Hospice Vermont- New Hampshire, feels patients share part of the blame. "I give immense credit to the oncologists," she says. "In the 20 years that I've been in end-of-life care, these people have been creating miracles. There are people surviving today we would never have thought would make it. But it's also contributed to why Americans are the only people who treat death as an option. The fact is, if we go to our physician wanting to live forever, unwilling or unable to open up to [the inevitability of death], we collude in this. I believe we've made great strides in [dealing with death]. More and more of us are going to a doctor saying, 'Here's what I want, here's what I know, help me do it my way.' But until we're all able to do that, it's not fair to blame doctors for doing it their way."

Kirn feels the crux of the problem is that "people afraid of dying see it as a time of giving up, and they see hospice as the death knell. The point is to help people earlier in their experience to feel in charge of their choices of treatment and medication, and where they want to be, and what they want to do . . . and to support them in doing whatever that is.

"We've turned death into a medical event in just handing it over to the doctors," Kirn goes on, "and we've forgotten it's a time when we have a lot to do that's spiritual, emotional, and interpersonal."

|

|

Jane Ackerman, coordinator of the palliative care project at DHMC's Norris Cotton Cancer Center, agrees: "The shift in palliative care is to care for the whole person, plus family and community —not just with the goal of attacking the tumor, but managing the welfare of the whole person in the last days.

"Palliative care is often called 'comfort care,'" Ackerman adds, "but it's more than that—it's a shift of the focus from beating the disease to living well during the time you have left. And the idea is to make this shift sooner rather than later, to prevent unnecessary medical, emotional, financial, and spiritual crises."

Educating the profession

Instruction in care of the dying is given varied attention at the nation's 125 medical schools, ranging from a single one-hour lecture to full courses devoted to the topic. DMS's "New Directions" curriculum reform project, begun in 1995, came at a fortuitous time for advocates of palliative-care education —it meant students would receive more and earlier clinical experience with dying patients. Since the fall of 1995, students have been able to select a "Palliative Care Education Through Quality Improvement" elective, designed by Goodlin and others as a way to develop skills in pain- and symptom-management, to directly affect the care of terminal cancer patients, and to evaluate and improve palliative-care techniques. In 1996-97, Kirn helped the DMS faculty design an eight-session course on end-of-life care. And third-year students take a full-day seminar on death and dying entitled "Living with Mortality: A Medical, Moral, and Spiritual Examination," designed by Kirn together with Dartmouth oncologist Joseph O'Donnell, M.D., and Julia Waldron of the Visiting Nurse Association.

"Dartmouth was one of the first medical schools in the country to incorporate hospice concepts into third-year students' 12-week medical-surgical rotations," says Kirn. Students find their time with a hospice volunteer "eye-opening," she adds. "There is nothing more instructive than tagging along on a home visit to a three- or four-generation family home, where the dying patient's hospital bed is set up in the kitchen with all the family activity revolving around it. For instance, one of the first things you notice is that the family is often under greater duress than the patient. Here is where you will learn to value and to practice familiarity, gentleness, and a manner of grace."

|

|

DMS student Rachel Solotaroff feels it's essential for medical students to discuss and deal with death. |

But third-year DMS student Rachel Solotaroff believes there should be even more such opportunities. "It's not that nothing is currently being done," she says, "it's just that far more has to. For example, how to do patient screening and how to handle difficult conversations with patients."

Goodlin agrees: "We believe the skills, attitudes, and behaviors necessary to good care of dying patients are fundamental to being a good physician."

Solotaroff thinks that "the only way for medical students to gain comfort in dealing with death and dying is to confront and resolve their own fears and attitudes about it." So last year she and a group of her classmates began spending Wednesday nights at the Kendal lifecare community in Hanover, discussing with residents the spiritual and practical aspects of death and dying. And along with a dozen or so other DMS students, Solotaroff has also volunteered for a "vigil squad," whose members are trained to spend two-hour nighttime shifts sitting by the bedsides of people dying alone at DHMC. "You have no business sitting in a dying patient's room if you haven't faced these issues yourself," Solotaroff says. "We have so much to learn, starting simply with what to say to patients facing the ends of their lives."

"Most of these kids have never seen a peaceful death," says Kirn. "They ask, 'What do we do for two hours?' Well, you may not do anything but just sit and be present to the mystery of it all."

|

The NCCC Principles of Care DHMC's Norris Cotton Cancer Center has adopted these principles of care as a contract between the NCCC and its patients:

|

Palliative care at DHMC

For patients with lives derailed by an out-of-theblue terminal diagnosis, even a hospital designed to be user-friendly can be a frighteningly complex place. Without help negotiating the wilderness of symptoms and the maze of therapies, patients may simply wander from appointment to appointment, until finally—when their disease seems no longer curable—they are left with a feeling of abandonment by the very system in which they have invested their trust, hope, and, in some cases, their life's savings.

What would it take to keep them from beginning such a terrible journey on the wrong foot—especially in rural areas, where a full range of services can be hours away? Perhaps simply an integrated approach to each individual's case: someone to coordinate the management of their illness and of their treatment's side-effects, to make sure they are heard by clinicians (and vice versa), to provide counseling for their family and caregivers, and to help them consider the emotional and spiritual aspects of the end of life. Ideally, all this should spring from the patients' own needs, values, and preferences —and it should begin the day of diagnosis and continue through whatever comes.

It takes a complex program to respond to this seemingly simple need. Yet DHMC's Norris Cotton Cancer Center (NCCC) has recently begun one, starting with the institution of three fundamental improvements in its approach to cancer care; the aim is to eventually expand the program to benefit every DHMC patient who receives a diagnosis of a life-limiting illness. The plan begins with a three-part initiative:

- adopting an explicit set of "Principles of Care" (see the box on the facing page);

- integrating palliative-care and symptom-management approaches into the care provided to all NCCC patients through a brand-new "Regional Palliative Care Initiative"; and

- extending this new approach out into the community through a second new program called "Project ENABLE."

Momentum in palliative care has been building at DHMC for some time, as staff have done research, attended seminars on end-of-life issues, and applied their new insights clinically. One result was the establishment of the Center for Psycho-Oncology Research, headed by Peter Silberfarb, M.D., and Tim Ahles, Ph.D. (who, with Marguerite Stevens, Ph.D., is heading up the NCCC's new regional initiative). The Psycho-Oncology Center has been conducting studies and counseling patients — and their physicians — on the psychological impact of life-threatening illness and chronic incapacitation, on the use of medications in such situations, and on the coping skills needed to deal with disease and its treatment.

|

|

Two new programs

But the palliative-care ball began really rolling in earnest when, two years ago, the NCCC asked the Byrne Foundation, a local philanthropic organization, to fund the establishment of the Regional Palliative Care Initiative (RPCI). Its goal: to integrate palliative care into the very framework of DHMC—and ultimately across northern New England, via the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Clinic (a multispecialty group practice with more than 30 sites in Vermont and New Hampshire) and the Dartmouth- Hitchcock Alliance (a collaborative system of hospitals and health-care agencies throughout the region). In full support of the idea, the Byrne Foundation promised $2 million over the next five years, beginning with funds for an intensive year of planning guided by outside experts, a process that was already underway.

According to the NCCC's director, E. Robert Greenberg, M.D., setting up such a program and making it a success hinge on several key elements:

- gaining the ongoing support of DHMC;

- making the program as cost-effective and selfsustaining as possible;

- training practitioners and students in patientreferral and care-coordination;

- developing written guidelines for pain- and symptom-management; and

- informing the public that palliative service is available.

Also essential to the project's success will be bringing aboard an accomplished and motivated director. With many of the country's major medical centers simultaneously embarking on similar efforts, and not many experts trained and experienced in this relatively new discipline, recruiting a leader is the Dartmouth program's biggest challenge.

Less than a month after receiving the RPCI grant, in January of 1998, DHMC applied for a second grant—this one from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation—to establish "Project ENABLE" (the acronym stands for "Educate, Nurture, Advise Before Life Ends"). This would be how the RPCI would reach the grass-roots patient population it aims to serve. In September of 1998, DHMC was one of just 20 institutions (out of 700 applicants) whose proposals were funded—this time to the tune of $500,000 over three years (which will be matched with funds raised by the NCCC).

"The underlying premise of Project ENABLE," wrote its creators in the grant application, "is . . . patient choice. . . . Regardless of their geographic location, cultural identification, or clinical sophistication, patients need not feel abandoned when a cure for their disease seems no longer possible."

There are two main aspects to ENABLE. First, it will put patients in touch with a local palliativecare coordinator at the time of their diagnosis; the coordinator will help patients integrate all their care throughout the course of their illness, including hospice and home care. And second, it will offer patients a series of seminars—four a month— designed to empower them to oversee their own care, to give them information, and to help them navigate through the health-care system. The hope is to create from the seminars a package of videos, written materials, and other resources that can be used at other sites around the country.

Greenberg hopes that as patients become informed about palliative-care options, they will begin to request them, initiating the same kind of sweeping change catalyzed by the informed-childbirth movement of the 1960s. In many ways, the seminars—called "Charting Your Course: A Whole-Person Approach to Living with Cancer"— mirror the concepts of the birthing classes that aimed to enhance communication and ease anxiety for expectant parents, only here they bring these principles to bear on the final phase of life.

ENABLE is now underway in three New Hampshire demonstration sites—Lebanon, Manchester, and Berlin—selected for their geographic, clinical, and cultural diversity. The first patients admitted into the program had lung, advanced gastrointestinal, or metastatic breast cancer. Those conditions were chosen because most such patients are likely to require end-of-life care within two years.

Each site has a palliative-care team with a painmanagement specialist, an oncologist, a clinical nurse specialist, a psychiatrist or psychologist, a hospice/ home-health-care liaison, a social worker/case manager, and a pastoral caregiver. In more rural areas, some of this expertise will be provided via telecommunication from DHMC.

|

|

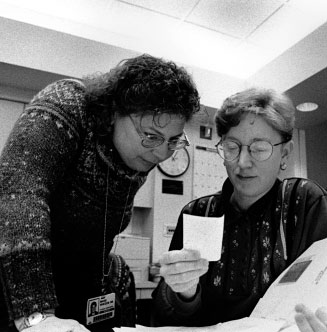

Marie Whedon, left, is overseeing the clinical aspects of Project ENABLE with Karen Skalla, right. |

Early in the course of their illness, patients are interviewed and evaluated by their site's palliativecare coordinator and are encouraged to attend the seminar series. Thereafter, the coordinator facilitates clear communication between patients and physicians, trains patients and their families in symptom- and stress-management, helps with their advanced-care planning, and links them with the services provided by area hospices and homehealth- care agencies.

Perhaps the most important job of the coordinators is to encourage patients to make their own decisions about the course of their treatment, by guiding them in considering not just the stages of disease and death, but also their associated feelings and beliefs. This is a role welcomed by the members of Solotaroff's Kendal-DMS partnership. In response to the question, "When faced with a terminal illness, what do we want from our physicians?" the Kendal residents generated a list of requests; nearly every item on it asks for compassion and understanding rather than healing. And they end with a warning: "Be comfortable with my wishes, or I'll find myself another doctor!"

Conceptually, the project aims to eliminate from ordinary parlance a phrase that DHMC clinical nurse specialist Marie Whedon, M.S., R.N., finds anathema: "Incurable cancer is not a condition 'beyond medical help.' There is a tremendous amount that can be done to ease the illness and the suffering —physical, psychosocial, and spiritual—that can accompany [a terminal illness]. It annoys me when people say, 'There's nothing more we can do.' That's precisely when there's lots more that you'd better do. Patients are often unaware, or forget, that it is the duty of professionals in the medical field to care as well as to cure."

What's needed, explains Whedon, is for both doctors and patients to look on their relationship as more of a partnership. The concept of "partnership" has another element as well. A key objective of the three-site test, says Greenberg, is to demonstrate the effectiveness of the academic-community partnership —specifically, the ability of community physicians, hospice specialists, home-health-care agencies, nursing homes, and professionals at an academic medical center to all work together. "People should be dying close to home, not in tertiary- care centers. If this model proves effective, more and more patients at the ends of their lives are going to be out in the community, and yet the research [on the best palliative-care practices] will still be occurring in the academic centers, which are set up to do it. That's a big reason for the importance of the partnership."

Tomorrow the region

"This program is not about death," emphasizes Ackerman. "It's about living as best you can, as fully as you can, with end-stage cancer or heart disease or pulmonary disease or neurological disease. And although we're building the program in the Cancer Center, we're doing so with an eye to extending these principles throughout DHMC."

Project ENABLE has now been fully implemented at all three demonstration sites, and the response has exceeded the organizers' expectations, says Whedon. "We estimated maybe 300 people would be identified as candidates per year, and that was generous. Of those, we expected [Lebanon] would enroll a little under half, so we thought 125 [a year] was the number we could count on. Instead we got 138 in less than six months." In addition, 100 have been identified in Manchester/Hookset and 20 in Berlin.

Focus groups have been held at all three sites to assess the seminars. "They want us to offer the seminars to everybody, not just those with these three cancer diagnoses," says Whedon. "We're trying to figure out how to deal with the success of this."

|

|

Greenberg, too, is pleased with early reactions— particularly the willingness of many DHMC clinicians, especially oncologists, to become involved. Along the way, some myths are being exploded. "Around the country," he says, "there's a notion that it's very hard to get oncologists to support this idea. One of the funding agencies expressed strong doubts we'd be able to get ours—and even less likely, those in the community—to go along. Yet we've had essentially 100% cooperation. Everyone, once the program has been explained to them, has been very, very supportive."

Still, he cautions, the projects are proceeding deliberately, and for good reason: "There have been some palliative-care initiatives here before that never really gathered a lot of momentum, because they were coming more from individuals. We need to make sure we gather broad support, involve the right people, let people know what we're doing and what we're thinking about, and think things through. It would be very easy to go off half-cocked and waste time and money and good-will."

Nevertheless, his enthusiasm is contagious as he ticks off the project's strengths: "A core staff of highly motivated, deeply committed doctors, nurses, and administrators . . . the commitment of DHMC's leadership . . . funding in hand that can leverage other sources of support . . . the NCCC initiating, testing, and proving the efficacy of these programs. . . . Taken together," he concludes, "it's difficult to imagine a more fundamental covenant for the sustained provision of palliative care for dying patients, throughout the state, the region, and perhaps the nation."

Marie Kirn's sights are set equally high. It's been 25 years since she wrote a letter to Elisabeth Kubler- Ross and was invited to lunch. What they discussed turned Kirn's life around. Abandoning her career as a management training specialist, she started gathering like-minded people into what became, five years later, the Monadnock, N.H., Hospice. Six years ago she brought the model to the Upper Valley.

"For 25 years," says Kirn, "hospice has been operating outside the system—telling it, 'You're not doing it right.' . . . Eighteen years ago, I stood on a stage and said, 'If we do this well it's possible that we may have to give it away someday.' Well, today I'm happy to say I'm not giving it away: I'm taking it to the next level—something we couldn't do without [DHMC] involvement and without larger funding. It's just so rewarding to see that now, 20 years later, medical schools, along with hospitals and cancer centers, are finally 'getting it' that what hospice has been doing is truly important."

And in northern New England, they are all doing it together.

Mary Daubenspeck is a freelance writer based in Lyme, N.H.