Dateline: Burma

By Alan K. Lathrop

It was 1942 in the brutal China-India-Burma Theater. A young Dartmouth-trained doctor assigned to a medical unit headed by the famous "Burma surgeon," Gordon Seagrave -started keeping a diary on whatever scraps of paper he could find. Published here for the first time are excerpts from his harrowing account:the endless casualties,the numbing fatigue, and details of the legendary Stilwell "walkout."

"April 1. Start of war for me and brief diary." So wrote Dr. John Grindlay as he flew from China to join a few dozen other American soldiers in Burma. It was 1942 and Grindlay, a housestaff alumnus of Dartmouth, had been in Asia since the previous September as a medical officer with the American Military Mission to China. AMMISCA, as the mission was called, had been organized by the War Department to administer the delivery of Lend-Lease supplies for use by the embattled Chinese government of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek in its fight against the Japanese. Grindlay and 47 other Americans were stationed in China and Burma under the command of Brigadier General John Magruder.

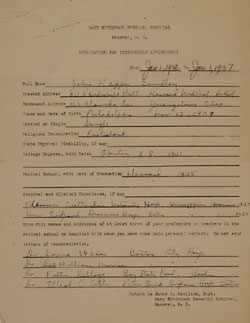

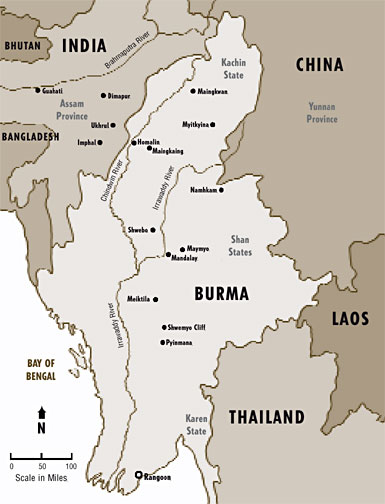

Grindlay had graduated from Oberlin College in 1931 and from Harvard Medical School in 1935. After two years at Dartmouth—first as a fellow in pathology and then as a rotating intern at Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital—he did a fellowship in surgery at Mayo and earned an M.S. in surgery at the University of Minnesota. In 1940, he joined the U.S. Army Reserve. He was a first lieutenant by the time he volunteered for AMMISCA in September of 1941. A promotion to captain came early in 1942, shortly before he was assigned to Burma. The Japanese had invaded southern Burma through Thailand in December 1941. The woefully outnumbered, outmaneuvered, and ill-equipped British and Indian forces defending the British colony retreated steadily ahead of the superior enemy forces. Rangoon, the port through which Lend-Lease supplies arrived for transshipment up the Burma Road to China, fell to the Japanese on March 8. By the time Grindlay arrived in Burma at the beginning of April, the front was in the vicinity of Pyinmana, some 200 miles north of Rangoon (see the map on page 33).

|

|

Grindlay's unit traversed many a dusty central Burma road like this one. These are Chinese soldiers, and the photo is from the mid-1940s. |

The Chinese government was alarmed at the prospect of losing the vital Burma Road, the only overland supply route into China, and in December had offered the British several divisions of troops to help fight the Japanese. The Chinese troops began arriving in Burma in January, but it was not until mid-March that they were deployed in force along the eastern sector of the front—too late to save Rangoon from capture.

In late February 1942, the U.S. War Department assigned Lieutenant General Joseph Stilwell to serve as Chiang Kai-shek's chief of staff and as the administrator of the Lend-Lease program. Stilwell was also given command of the Chinese troops and of all American forces in Burma, China, and India. When he arrived in Burma on March 19, he found a chaotic and nearly hopeless situation. The British were trying to hang on until the monsoon broke in late April or early May, in hopes of reaching the evacuation trails to India ahead of the Japanese. Adding to the confusion was the reluctance of most Chinese army and divisional commanders to follow anyone's orders except Chiang Kai-shek's. But oftentimes, Chiang's orders were contradictory or capricious. Stilwell's depressed mood was reflected in his own diary entry for April 1, written after two weeks in the field and the same day Grindlay arrived in Burma: "April 1—April Fool Day. Am I the April fool? From March 19 to April 1 in Burma, struggling with the Chinese, the British, my own people, the supply, the medical service, etc., etc. Incidentally, with the Japs."

The medical service of which Stilwell was complaining was conspicuously inadequate to deal with the flood of casualties coming from the combat areas. The Americans had no field hospitals, nor did the Chinese. Their medical needs—as well as some British needs—were being handled by Dr. Gordon Seagrave, the famous "Burma Surgeon." (Seagrave wrote about his experiences for the July 20, 1942, issue of Time magazine and later published two books—Burma Surgeon in 1943 and Burma Surgeon Returns in 1946.)

The son of Baptist missionaries, Seagrave had been born and raised in Burma. After graduating from Johns Hopkins Medical School and completing an internship at Union Memorial Hospital in Baltimore, he and his wife settled in Namkham in the Shan States of northeastern Burma in 1922. There, they ran a hospital which by 1942 had a capacity of 100 beds and a staff of two doctors, plus 11 native nurses (later increased to 19) whom he had personally trained. After the war in Burma broke out, Seagrave and his unit were assigned by the British to offer mobile medical support for the Chinese Sixth Army, operating in the Shan States and the Karen State in eastern Burma.

After Stilwell arrived, Seagrave requested that his unit be placed under American command. Stilwell agreed and subsequently ordered the medical group to move just behind the front lines at Pyinmana. Seagrave and the nurses moved their mobile surgical hospital into an old agricultural station. Seagrave was also informed that a volunteer group called the Friends Ambulance Unit (FAU) would join them. The FAU was composed mainly of young British Quakers who had been working in China before transferring to Burma. These men, seven in number, were indefatigable workers whose valor would be proven time after time in the weeks to come.

|

With the establishment of Stilwell's command in March, AMMISCA was disbanded and its personnel scattered. Grindlay was ordered to Burma on March 28 and notified that he was joining Seagrave's unit on April 2. The next day he reported to the hospital, after a hot, dusty jeep ride from Maymyo, where Stilwell had his headquarters. "Another captain turned up today while I was matching the nurses for blood transfusion," Seagrave wrote in his diary. "Captain Grindlay trained in the Mayo Clinic. . . . Looks just like a Mayo Clinic man, too! I will have to keep a stiff upper lip and do the best surgery I can." Records show that Captain Donald O'Hara, a dentist in the U.S. Army, also arrived that day.

Grindlay had no sooner joined Seagrave than the FAU brought in two truckloads of Chinese bomb casualties. His diary captures the breathless pace of the work and the horrible injuries that occupied him that morning and for the next month. "One had two legs off at thigh and horrible burns. Sick at stomach. Scrub. Just started amputating the legs of this case when he died. Then I took one [with] shrapnel [wound in] buttock. Found it passed in front of sacrum. Opened belly—full of blood. Ten holes in p.i. [proximal ileum—the small intestine] and probably pelvic vein torn. Died. Seagrave working on another belly case—it died. Both worked on a brain case—two large trephine holes parietal region, torn and bloody brain. Vaseline wick."

The Friends came in from the front lines and said that the Chinese forces were retreating to positions behind theirs, leaving the hospital exposed and undefended. "Worked like hell—nurses harder than I— until 1:00 p.m. Sent 30 [patients] to Meiktila [a city about 90 miles north of Pyinmana]. . . . Took brain cases and two plaster cases [with] us on end [of] one truck. Everything else packed up. Left 1:15 p.m. . . . Wound over side road to . . . Shwemyo Cliff. About 30 miles north [of Pyinmana]." The doctors and nurses unpacked at a former Public Works Department bungalow on top of the bluff and got settled. They finally were able to get to bed at 4:00 a.m. and slept for five hours.

|

|

Above is John Grindlay in a photo taken in 1937, just after he left Dartmouth for further training at the Mayo Clinic. Below is his original Dartmouth-Hitchcock residency application. |

|

The Friends who had driven the 30 Chinese patients to Meiktila returned at noon. Their trucks, Grindlay reported, were "strafed along the road. Four tires and radiator connector tube hit on one truck and it had to be towed in. Hot and windy—dry. Forest fires and haze. . . . Scorpions and cobras about here. Numerous air alarms—about every half hour a flight of Jap bombers passes down valley. Tried to nap. Got tired of running to gulch behind us [with] girls."

A report came in of soldiers wounded by the strafing. One of the Friends went off in a truck to check. He returned at the end of dinner ("the inevitable rice, soup, and spiced beef stew-slop") with one patient aboard. The driver said two more truckloads were following. Grindlay pitched in immediately, working by lamplight. "I hopped on the case and got going—had through-and-through bullet [wound] right wrist—shattering ulna—and through-and-through [wound] right hip to left scrotum, hitting greater trochanter [and] crest [of the] ilium and destroying left testes. Took out left testes, debrided scrotum, and drained both sides. Debrided hip and wrist and did a Trueta cast [a kind of cast named after a Spanish orthopaedic surgeon] of right arm. . . . Lamplight and bugs. . . . High wind."

After supper the next day (April 5), a "hot, windy day," Grindlay helped pack up and move the unit to Tatkon, a town eight miles north of their previous location. The nurses worked hard, as usual, and lent an air of civility to the proceedings by singing. "Girls singing native Kachin, Burmese, and English and American songs," Grindlay wrote with admiration. "Affectionate, pretty, hard-working little creatures."

They arrived at their new quarters, a school, at midnight, unloaded, and went to bed. Grindlay himself was suffering from "renal colic and tough backache." He took "a slug of Drambuie and got enough relief to put out bedding. Got little sleep during night [because of] my back; the colic did subside, though."

|

|

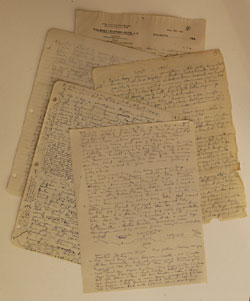

Above are several representative pages from Grindlay's diary, which he kept on whatever pieces of paper he had at hand—lined notebook paper, plain unlined paper, and even a few pieces of hotel stationery. Below are Chinese troops in a village in northern Burma much like the ones where Grindlay's unit stayed in their effort to keep ahead of Japanese forces. |

|

The unit moved again the next day—a quarter-mile up the road to a less sheltered but somewhat more comfortable facility. The day was quiet and Seagrave was able to organize a hymn-sing by the nurses that evening. On the morning of the 7th, the Japanese strafed the Chinese troops on the road below the hospital and the Friends went out to pick up casualties while Grindlay, Seagrave, and O'Hara scrubbed. "About 1:00 [p.m.] the trucks returned—34 wounded, only one [with] minor [wounds]. Two brain cases died on table. Rest all horribly shattering compound fractures, etc., requiring lots of work—several needing amputations. Soldiers filthy and lousy [with] lice and scabies, malaria, and probably syphilis and tbc [tuberculosis]. Worked alone from 6:00 p.m. on while Seagrave went for supplies. One 'storm-king' lantern. Usual bugs and poor asepsis. Back (right kidney) aching. Finally finished 11:00 p.m. and ate usual slop."

Twenty-five more casualties were brought in after breakfast the next day; four had malaria and the rest had been wounded. "Two belly cases two days old. I did one and resected two feet [of] bowel—a tough job. All our cases have at least one serious shattering [wound], most have two or three. One I did yesterday had four bad compound fractures."

On the 10th, Grindlay rolled out of bed at 10:00 a.m. feeling "more dead than alive." Everyone pitched in to clean and disinfect the dining room, hospital, and dispensary. Meanwhile, casualties continued to pour in. After lunch, 35 wounded arrived. "On one I took out a spleen (bleeding from bullet [wound]), [with] an untrained nurse and bugs falling into [surgical] field."

By the 14th, Grindlay reported "no pep left in me." The frantic pace was getting to him. Thirty-five wounded were brought in at 10:30 p.m. and he worked on them until 2:00 a.m. "I had two belly cases to start. One with hole in liver which I packed and one [with] hole through splenic flexure—for which I did a transverse colostomy (no feces in belly and I put a drain through to the splenic flexure region). Other horrible, dirty, shattering wounds— one with buttocks and anus ripped off for whom I did . . . some of Harrison-Crips operation." He also wrote that many Indian soldiers came in with dressings made of a paste of chopped leaves, which made for "badly infected" wounds.

The intense heat made rest extremely difficult. "No sleep today. Too blasted hot," Grindlay wrote on April 16. That day, word arrived that the Japanese were advancing in two prongs, one up the Irrawaddy River through central Burma, the other through the Shan States to the east. "Seagrave knows the geography well and thinks we are in danger of being cut off. Just as I got to bed another truck of severely wounded. Only 15 patients, so I did them alone and got to bed 4:30 a.m. Very tired and feeling lousy."

On April 18, Stilwell ordered Seagrave to evacuate to north of Meiktila. "Off before the [Chinese] had the road blocked [with truck traffic]," Grindlay wrote. "On to Meiktila in burning sun over scorched desert." He and Seagrave scouted for a new location and finally found a former government bungalow just outside the town of Kume. "Has a fine wall and lots of water in the canal by door." The house was surrounded by palm trees with ruins of pagodas across the canal. The locals soon constructed a thatch-roofed operating hut next to the house.

|

On April 21, while Seagrave went off to Stilwell's headquarters to protest Grindlay's rumored reassignment to another mobile surgical hospital, wounded continued to stream in—truckload after truckload, "all the burning hot day and right through the night. O'Hara had several jaw cases and did a few other small cases. Otherwise I was alone, living on coffee and cigarettes; bloody, plaster- coated, sweaty, wearing only Shan pants and shoes. Many plaster cases—[compound fractures of] femurs, etc." By 2:00 p.m. the next day, they had worked on 120 cases, "all bad," Grindlay wrote. "Absolutely exhausted—twitching and temper short."

He was asleep "in heat and flies after lunch" when Colonel Robert Williams, Stilwell's commanding medical officer, came in and woke him. The news was grim: the Chinese Sixth Army, which was defending the area around them, had fallen apart under Japanese attacks. They might stay in the Meiktila area another week, then evacuate. With the Japanese threatening to cut the Burma Road, retreat to India was rapidly becoming the only option. That night Grindlay fell into bed so tense with exhaustion that he took some sleeping pills to relax.

On April 23, Seagrave returned from seeing Stilwell with a commission as a major and the word that Grindlay would stay on with him. The unit spent only two more days at Kume, operating steadily with little rest on a torrent of casualties. On the 25th, they were ordered to move north to Shwebo. Grindlay had finally gotten over his renal colic by then. "Started packing 5:00 p.m. Usual mess and confusion but off about 9:00 p.m." The group got separated in the darkness and mass of British tanks and trucks on the road. Grindlay "got the rest together . . . and led them over Ava bridge over Irrawaddy [near Mandalay]. Held them in Sagaing village on other side until Seagrave came up. Then found a camp along river in an [American Baptist Missionary] compound. Some slept on pews in church. . . . I slept [with] the Sikhs on the lawn. Very tired."

|

|

This is the only extant photo of Grindlay during the war, for his camera was stolen just before the "walkout" to India. Grindlay is on the far left, and Stilwell is seated next to him. |

At Shwebo, Grindlay saw Stilwell and his staff and was asked to stop and share a whiskey with them. They were "idle and awaiting decision from [Washington] and Gissimo [Chiang Kai-shek] what to do. Battle [of] Burma over. . . . Stilwell talked [with] me for long time about type of medical equipment to take [in retreat from Burma] before going to bed. Doesn't regard [Colonel] Williams's opinions. Next move is rumored to India, unless we have to go to China." Grindlay was hoping that they would head for India, however.

On the 28th, the group got the word: "Present plan is by rail to Myitkyina and then walk or plane to India." He and Seagrave drove to Shwebo next morning. Soon after they arrived, 27 Japanese bombers went "over and dropped about 150 bombs. I just laid on ground and passed cigarettes. Seagrave and I drove through town looking for casualties, but no one but soldiers in town. Bomb holes, fallen trees, and huge fires blocked most of streets, and there were [occasional] explosives." The group returned to Shwebo late in the afternoon but still saw no casualties. They found a bottle of gin and drank it on the way home and thus "arrived tight," Grindlay wrote later.

|

|

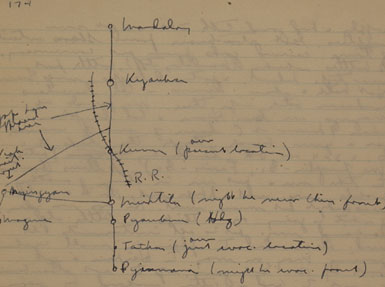

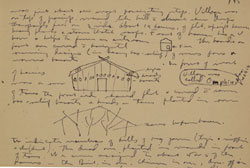

Above is a map of the region where most of the unit's peregrinations took place. And above is a sketch of the area between Pyinmana and Mandalay that Grindlay drew in his diary. For the most part, however, his entries are tightly written from edge to edge on both sides of every page —as evidenced by the writing showing through from the other side, below. |

|

During the night of May 2, General Lo Cho-ying, the Chinese chief of staff (Stilwell's counterpart), panicked and commandeered a train at Shwebo and tried to drive to Myitkyina. Partway there, he crashed head-on with a southbound train, which totally blocked the line. Stilwell therefore decided to take motor transport as far as possible. The days that followed were a mad rush as the Seagrave unit, including the Friends, prepared to leave Burma and trek with Stilwell into India. They drove north and west until, on the morning of May 6, the vehicles were abandoned when the road ended at a small bamboo bridge. There, all nonessential articles of clothing and equipment were discarded. In the confusion, someone stole Grindlay's camera, with photographs he had taken during the previous several weeks.

The group sent out a final radio message: "We abandon all transportation here. Our route will be Maingkaing—by raft down the Uyu River to Homalin—across Chindwin [River]—on foot over mountains to Ukhrul and Imphal. . . . This is our last radio message, repeat our last message. Stilwell." Then they took turns smashing the radio beyond repair to prevent it from being used by the Japanese, and also burned their codes and all file copies of messages. The group then lay down on the grass next to a stream to rest up for the strenuous day that they knew lay ahead of them.

The next morning the "walkout," as it came to be called, began. Grindlay's comments in his diary reflect the pain, discomfort, exhaustion, and danger that the party experienced in the days that followed. By this time, the entourage included native guides, Stilwell's staff, his Chinese bodyguards, a contingent of British officers and enlisted soldiers, a couple of former British forestry officials, plus Seagrave's unit and the FAU.

"Off after daybreak [with] General Stilwell leading and carrying Tommy gun," wrote Grindlay. "Crossed river wading. . . . Then down the primeval jungle river, the long, undulating single-file column led by yo-yo pole-toting, high-stepping Burman, then Stilwell. Girls kept me in line (exhausted) and sang—causing those ahead to turn about (they were all exhausted and thought morning's hike equal to a 30-mile march). Tea on bank along river then down river for a mile in pitch black—meeting luminous water rushes; feet now blistered and blisters worn off." They tried to sleep that night beside an elephant camp but were disturbed by the jangling of the animals' wooden bells all night long.

Two days later, they reached the town of Maing-kaing on the Uyu River, where they built rafts of bamboo and floated down the Uyu for three days to the settlement of Homalin. There Stilwell's group received an air drop from the British—bully beef, biscuits, tea, and cigarettes. Grindlay and some of the nurses wove roofs for the rafts to ward off the torrid sun: "Won admiration [from] Stilwell, our group did, and his appreciation later, for [without] mat roofs it would have been unbearable."

On May 13, the group was met by a mule pack train from Yunnan—one of those that regularly plied the opium trade route across northern Burma from India to China. With its help, they began the steep climb over the mountains into India. The next six days were grueling: the monsoon broke, and with it came drenching rains that turned the steep trails to mud.

On the 14th, they met Tim Sharpe, the head of the British governing body in Assam Province in India. Sharpe brought pack ponies and porters. Men, mules, and horses slipped, slid, and stuck in the mire as they trudged up and down the heights of the so-called Naga Hills. Grindlay wrote: "Uphill over very steep trail, [with] alternate dense jungle and open dense, tall jungle grass patches. . . . For last hour of stiff climb had drenching tropical thunder shower."

|

It was more of the same on the 15th: "Up early. . . . Up very stiff trail, largely through jungle grass [with] marvelous view Chindwin and Uyu [River] valley—we can see easily our entire course of past [week]. . . . Hot, sunny, shadeless, humid. . . . Again passing rain for last two hours; cold as we crossed a knife-edge cornice, wetting the trail, causing our 28 horses to slip, drenching and chilling us. Just before dusk, on down slope of ridge [with] fleecy clouds below and last view of Chindwin behind for good, arrived at a Kuki village. . . . Another full meal, drying of clothes and to bed." The Kukis, along with the Nagas, had inhabited these hills for centuries and were staunch allies of the British.

The weary travelers needed their rest, for on the following day they crossed "over a [mountain] shoulder and down to the deepest chasm of a rocky ravine I ever saw. Then up the longest, steepest, hottest, grinding trail, passing over the ridge and just beyond to our noon halt. Terrible strain—the men all nearly collapsed, several of the girls very weary, and I had to have them await the ponies." At a halt for lunch in a village inhabited by Naga tribesmen, they were served frothing rice beer in gourds and an unidentified alcoholic beverage that they sipped through a bamboo straw. "Got a bit of a jag . . . on these two," Grindlay wrote.

Off again at 2:00 p.m., the group descended a steep gorge, reaching the bottom at 4:00 p.m. and camping there in four long thatched sheds of bamboo, sleeping on platforms made of bamboo branches. "The knots and bends of the branches were hell—and turning over an experience. Bathed in rushing river and ate—all very cramped and smoky." Grindlay had contracted conjunctivitis a few days before, and the smoke made his eyes "terrible" with irritation.

By this time the group was more than 20 miles into India. At noon on the 17th, they stopped at another Naga village, where Grindlay observed trees "hung [with] tiger and miffin skulls." They walked 14 miles in half a day over rugged terrain, and after a lunch of tea and biscuits "went on up, up, and up through pine forest to village of Omphin," on a hilltop. There, in an "alpine setting [with] huge sheer mountain backdrops," it was "cold, clear, and dry." The group referred to this as the "flea stop," because they spent the night scratching flea-bites.

On the 18th, they zig-zagged up over a ridge that was several thousand feet high by Grindlay's estimate. They had seen the trail the day before from the other side of the valley. After another steep descent and climb they reached Ukhrul, the largest village they'd yet encountered, at an altitude of 6,500 feet. The travelers took baths "in icy air in [a] well, and girls washed clothes. Had clinic for feet and drying clothes by roaring fire in our house. Picked fleas. . . . Did 21 miles today."

The next day, they set off at 5:30 a.m. and were soon hit by drenching rain. "Kept along ridge for 11 miles in clouds and rain and bitter cold." They descended a steep, slippery trail and then headed up a steeper one. The noon halt for sausage and biscuits was in rain and clouds. It was so muddy that they could not sit down. The rain finally stopped after lunch and they began to dry out.

|

|

This photo of carts passing through a village in the northern state of Kachin probably dates from late 1944 or early 1945—just a few years after Grindlay's experiences in Burma. |

The days of grueling climbs and descents were taking a toll on Grindlay. "I was getting absolutely exhausted for some reason," he wrote on the 19th. Late that afternoon, the group reached a narrow steel suspension bridge, "on other side of which was end of motor road [from India]." Stilwell lined up the unit and told them that trucks were coming, and that there was better ground across the bridge and to "plan to camp there. Then he took me aside and asked about health of the ill ones—Seagrave taking too much sulfanilamide accounts for his symptom of heart [disease], etc., I thought." Seagrave's unit set up camp in an auto shed on the other side of the bridge, kicking out some Indian refugees already there.

A party of American officers soon arrived—men from Stilwell's staff who had been evacuated from Burma by air before the walkout began. They had been ordered by Stilwell to prepare for the arrival of their commander and his group. Stilwell called everyone together to hear the report of how these officers had tried to find the walkers. The last radio message had been received in India, "and this was all that they had in evidence we were heading for Imphal," a large town that was the capital of Manipur. Three nights before, a runner had been dispatched with messages from Stilwell and Jack Belden, and these disclosed for certain where the group actually was. "They brought in a couple bottles whiskey (I had a nip), a few cigarettes, and some chocolate (how delicious). Told us of outside news; most sensational was bombing of Tokyo by our medium bombers under Doolittle."

On the 20th, they traveled by truck to Imphal. Grindlay borrowed a razor and shaved off "my heavy red-and-white beard. Left mustache." The Seagrave unit treated several cases of malaria among the American officers who walked out of Burma. Stilwell's staff, including Grindlay, were put on a special train at Dimapur that took them to Calcutta, from where they were flown to New Delhi, Stilwell's new headquarters. There, in a new, air-conditioned hospital, the ailing personnel from the walkout—Americans, British, and Chinese—were treated by Grindlay and other doctors for several weeks.

|

|

Above is another of the sketches in Grindlay's diary—this one showing the structure of the houses in the village of Omphin, India, where his group spent a night in the company of some very active fleas. And at left is a whole page from the diary, which suggests the difficulty that the author of this article faced in merely deciphering Grindlay's handwriting. |

|

The rest of the Seagrave party stayed behind at Guahati, on the Brahmaputra River in northeast India. They eventually set up a permanent hospital at Ramgarh—a junction of several roads about 200 air miles northwest of Calcutta—to treat thousands of Chinese soldiers who were struggling out of Burma long into the summer and fall of 1942. In late July, Grindlay was ordered to rejoin the Seagrave hospital and arrived there on the 28th. He was welcomed with joyous "tears and shouting," he wrote. He became head of surgical services under Seagrave and "took over five 22-bed wards and OR." Stilwell visited the hospital in August and awarded the Purple Heart to both Grindlay and Seagrave. Grindlay also received the Bronze Star and, from the Republic of China, the Order of Yun Hui, for his services in Burma.

Grindlay remained at Ramgarh until mid-1943 and then moved to northwestern Burma with the bulk of the Seagrave unit to support the Chinese and American troops who were beginning to clear the Ledo Road (later renamed the Stilwell Road), an overland supply route being constructed from India to a linkup with the Burma Road at Myitkyina. Seagrave had gone ahead with part of the group in March and set up a hospital at Tagap Ga in the Hukawng Valley of Burma; later, he established other hospitals in a string down the Ledo Road to provide medical aid not only to the workers building the road but to the Nagas, who had been badly mistreated by retreating Chinese troops the year before. It was hoped that their respect and loyalty could be regained.

The war finally ended for Grindlay on January 20, 1944. He received orders to return to the U.S. almost two and a half years after he had left on what he'd believed would be a three-month stint. His diary ends abruptly on February 1 as he was flying over the Atlantic. For the rest of the war he was posted in Washington, D.C., at Walter Reed Army Hospital. He was reunited with Stilwell at Ft. McNair in October 1944.

In January 1946, Grindlay returned to the Mayo Clinic, where he received an appointment in the Institute of Experimental Medicine. He became head of the Section of Surgical Research in 1952 and a senior consultant in 1961. He was widely known for his research in experimental surgery and authored over 250 papers. He retired from Mayo in 1963 and died at his home in Colorado in December 1968.

Lathrop is a professor and curator of the Manuscripts Division at the University of Minnesota Libraries. He is working on a book based on Grindlay's diary from the entire war; this article draws on a portion of it. For ease of comprehension, the punctuation, spelling, and capitalization in the diary entries here have been standardized. No substantive changes were made in the quoted material, however, which means some terms that would now be considered derogatory appear as they were written in the 1940s. In a few cryptic diary passages, words have been inserted in [square brackets] to make Grindlay's meaning clear; any quoted passages in (parentheses), however, are in Grindlay's original text. The photographs are courtesy of John Grindlay's family, the author, and the Mayo Foundation's History of Medicine Library.

The author invites any and all inquiries and comments, especially from former CBI medical and military personnel and their families, as well as researchers interested in the CBI. Please contact the author, Alan K. Lathrop, at a-lath@tc.umn.edu.