Preteen film fare is the subject of a Dartmouth study

Imagine this scene: A young woman, alone in her house at night, answers the telephone. The caller, a man, engages her in a series of increasingly threatening conversations. She hangs up on him every time, but he keeps calling back. Terrified, she eventually realizes that he is at her house. Then the caller, dressed as Edvard Munch's subject in the painting The Scream, smashes a window, grabs her, stabs her repeatedly, drags her across the lawn, and hangs her disemboweled corpse from a tree.

Now imagine that you are 10 years old and have just popped the movie Scream into your VCR. You are about to experience that opening scene.

|

|

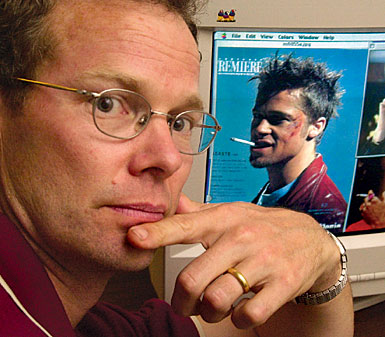

Pediatrician Jim Sargent says preteens today see a surprising amount of violence

in popular movies—such as the scene behind him of Brad Pitt in Fight Club, which

is rated R for "disturbing and graphic depiction of violent antisocial behavior." |

Content: Dartmouth pediatrician James Sargent, M.D., and his research team surveyed more than 5,000 5th- through 8th-graders from New Hampshire and Vermont in a recent study to determine the reach of R-rated movies among middle-schoolers. They coded the content of 600 popular movies—many of which contain scenes depicting rape, sodomy, and cannibalism—and asked each child which movies they had seen from a random subset of 50 titles.

They discovered that the reach of these violent movies among the younger population was much larger than they had expected. According to Sargent, Scream was the most popular R-rated movie, seen by 66% of the 5th- through 8th-graders (including 40% of the 5th-graders). Even the movie Natural Born Killers, which is rated R due to its "extreme violence and graphic carnage, shocking images, language, and sexuality," had been viewed by 20% of the study respondents and 13% of the 5th graders.

"What we wanted to point out with this article," Sargent explains, "is that these R-rated movies—that really are adult material—are being seen by a surprisingly high proportion of pretty young kids, starting at probably age 10."

Viewing violence: What is the effect of viewing violence at that age? According to Sargent, "it scares the young children and desensitizes the older children. It makes them less responsive to violence." In his practice, Sargent hears from parents who say that their children have returned from sleepovers afraid to go into their bedrooms. In conversation, up will pop the title to an extremely violent movie, like Friday the 13th. Sargent says he advises such parents to watch the movie themselves, so they can then talk to their children about the inappropriate things they've seen and help them process the material.

A child who perhaps only three years earlier believed in Santa Claus, adds Sargent, does not have the adult perspective necessary to understand these images. "It's a developmental process. They're really not ready to behave like adults until they're 20 or 21."

The problem, Sargent says, is that movies are everywhere now, and people don't think carefully about all the ways in which their children might come across such fare. It used to be that theaters wouldn't admit children under 16 to R-rated movies. That is no longer the case.

And besides, Sargent determined that about two-thirds of the study's respondents had seen the movies not in theaters but on TV (for which they are mildly edited), VCR, or DVD.

He feels that parental care is the solution. "The point of this paper is to cause people, especially parents, to think about what they let their kids see, and to try to hold the line as long as they can. I think it's better to have a kid that's relatively naive with respect to this kind of exposure than a kid that's overexposed. It's something that every parent has to think about."

Sargent encourages parents to keep media "in the box." How? Every television made since 2000 has a device called a V-chip, he explains, which allows parents to block certain channels or programs. All movies are rated, so a parent could program a V-chip to disallow anything rated TV-14 or higher.

Champion of the V-chip: But parents haven't been taught how to use the chip or been educated on its importance, Sargent believes. He would like to see if active use of the V-chip could affect kids' exposure to media.

Sargent intends to aim future research in two directions. First, he plans to conduct a regional study on interactions between parents and their kids regarding the media. About 15% of the surveyed children said their parents don't let them watch R-rated movies. Sargent wants to know how those parents differ from those who are more lenient. And second, he hopes to survey a nationally representative sample of kids to see if the findings apply to all areas of the U.S. and to different racial groups.

Katharine Fisher Britton

If you would like to offer any feedback about this article, we would welcome getting your comments at DartMed@Dartmouth.edu.