Egyptian outreach is two-way street for DMS urologist

Marc Cendron, M.D., a pediatric urologist at DHMC, may have gone to Egypt to share his medical expertise with nurses and physicians there, but he learned almost as much as he taught.

For one thing, he says, he learned "how to be more efficient in the operating room, use a lot less equipment, [and] operate faster." Scarce resources force Egyptian doctors to make do with less—they use only two sutures for a procedure for which the U.S. standard is four, for example —but they are often just as successful as their American colleagues.

And polluted air in cities like Cairo seeps into operating rooms, quickly rendering them unsterile, so surgeons have had to adapt by performing procedures faster than they might in a U.S. hospital. "The air, the environment, is basically cloudy, dusty, dirty," says Cendron. "The longer the patient's incision is open to the air, the greater the chance of . . . infection," he explains, "even though we do use antibiotics."

Expertise: As a volunteer with Physicians for Peace (PFP), Cendron traveled to Egypt last November with a team of specialists who shared their expertise with their Egyptian counterparts and helped children suffering from serious urological problems caused by birth defects, acquired conditions, and trauma.

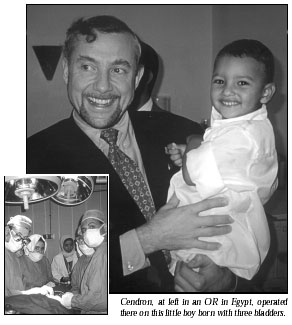

Physicians at upscale, state-of-the-art university hospitals, as well as at less-well-equipped hospitals, were all eager to learn from the Americans' demonstrations in the OR. One case involved a three-year-old boy born with three bladders; the U.S. surgeons successfully combined two of the bladders into one and turned the third into a urethra.

The PFP volunteers were also invited to lecture on up-to-date urological techniques to the Egyptian Urological Association. U.S. physicians feel it's important to correct urological problems in children at a very young age, for example, because they heal much better. "About 25 percent of birth defects involve the urinary tract," Cendron explains. But surgeons in Third World countries are reluctant to operate early because "they do not have the adequate anesthesia support to take care of these newborns," he says.

Overseas: Even before Cendron made this trip, he was an experienced overseas medical volunteer; he'd traveled to Egypt once before, in 1998, and had made two trips to Vietnam. He was surprised to learn that medical care in Vietnam was 50 years behind that in the Western world. "I was amazed to see techniques and procedures that had been in the textbooks a long time ago, but not anything that we practiced anymore," he says.

Physicians there were still using primitive techniques to drain pus from infected kidneys, for example. "They had never seen percutaneous drainage of a kidney," he says. They would do "a big operation to essentially open the area where the kidney is and drain out the pus." He was delighted to find an unused but functional ultrasound machine hidden in a closet. "We turned it on and we taught the physicians there how to insert a tube inside the kidney through the skin without having to make an incision in order to drain the kidney," he says.

Missions: Cendron would love to return to Vietnam and hopes PFP will send a team there one day. So far, since 1984, the organization has conducted over 200 medical missions in the Middle East (including 18 to Egypt), Central America, South America, Africa, Eastern Europe, the Caribbean, and parts of Asia. PFP also arranges for doctors, nurses, and technicians from these regions to visit U.S. medical schools and hospitals.

"I think this is an experience that every medical student and physician should have, just to put things in perspective . . . to illustrate how good we have it over here and how much we can contribute," Cendron says.

"It's a learning experience both ways," he adds. "Not only do you learn how these people work, how they learn, how they want to improve their ways of working, but they also learn from what you bring to them. I think the marvelous thing is that you really make friends with the people who are over there. The memory of having worked with these people under very different but difficult conditions is one that I think has improved my skills as a physician."

-Laura Stephenson Carter

If you would like to offer any feedback about this article, we would welcome getting your comments at DartMed@Dartmouth.edu.