DMS student proves himself tougher than the Hawaii Ironman

Late in the last leg of the 1999 Hawaii Ironman Triathlon—although maybe not late enough— Michael Bartholomew was running on his last legs.

It was partly, he knew, his own fault. After all, he was running on less than six months of training for this masochistic exercise whose victims—uh, participants —swim 2.4 miles in the Pacific Ocean, bicycle 112 miles, and, finally, for dessert, run 26.2 miles—the standard marathon distance. And do it back to back to back, under Hawaii's searing tropical sun.

Now, 20 miles into the third and final segment of the race, Bartholomew was wondering, not for the first time, if he could drag himself the last 6.2 miles. He'd already walked the previous three, during which, at one point, the disembodied voice of a race announcer had checked the bib number of this lanky 26- year-old and declared: "Michael Bartholomew, welcome to Hawaii! This is not Vermont."

Back home: No kidding! Back in his father's native Vermont, the leaves were bursting into reds and golds around Burlington, where Bartholomew had gone to college at the University of Vermont and, at the same time, been in charge of UVM's volunteer ambulance and rescue service. And across the Connecticut River in New Hampshire, his classmates at Dartmouth Medical School were just starting a new semester amid the glories of foliage season.

Now, as he baked on a treeless lava field, his years of going to classes while caring for patients (saving two heart-attack victims along the way) looked like a vacation. And the wall of information with which he'd been hit at DMS looked like a low curb compared to the physical wall he was hitting now.

Then he looked around and saw he wasn't alone. "I was gaining on some people by just walking," says Bartholomew a few months later, now bundled against the Upper Valley winter. "There was this one woman who was stooped over, barely moving. I asked, 'Are you all right?'" If she was, Bartholomew decided, he must be. Finally, two miles from the finish line, in the town of Kona, he shifted into second gear and then third.

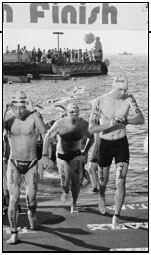

Biggest rush: "When you get to the edge of town, you kick in and you start running," Bartholomew recalls. "I'm glad I had the energy to run through town. It's dark by [then], but people lining the course are cheering you on. That's just the biggest rush." He crossed the finish line after 14 hours, 16 minutes, and 56 seconds in motion.

It didn't take him even that long to decide that "it was worth it. I'm glad I did it. It helped me with my confidence. It showed me that if I put my mind to it, I can accomplish anything."

Anything, including medical school. Bartholomew admits to having entertained doubts during his first year, which he ended up spreading over two years.

"There was so much to learn and to process that early on it really hurt my confidence," Bartholomew says. "I'd never felt the experience of having my confidence that low before."

Growing up the son of a Vermont farm boy who became an engineer for the Indian Health Service, and of a Kiowa Indian woman from Oklahoma, the 6-foot-6 Bartholomew had played high school basketball in Maryland, "hoping to get an athletic scholarship." But once he arrived at the University of Vermont, he decided that "I just wanted to have the whole college experience."

Squad: Whole, and then some. He worked for the UVM rescue service in almost every capacity for four years and directed it his senior year. "It was an eye-opener," Bartholomew says. "I did it as a test case, to see whether I wanted to go into medicine, and I learned so much. Running the squad opened my eyes to the politics and the management involved in being part of an organization. . . . I was managing finances, assigning people."

He wasn't, however, getting as much exercise as he was used to. By the time he got to medical school, a little intramural basketball was as much as he could handle. Looking for something to work off his frustrations, he checked out the Hawaii Ironman Triathlon—the world championship in the event. "I thought, 'Maybe I'll shoot for the Super Bowl first, and then scale back.'"

In January of 1999, he entered his name for one of 150 lottery spots for U.S. entrants (most participants are selected based on time) and promptly forgot about the prospect. "Then in April," he says, "I looked on the Web site, and lo and behold, there was my name."

And there was the rub. "At first I thought it was great," he says. "Then it was, 'What did I get myself into?'" He'd gotten himself into a race just to make it to the starting line.

"I'd been doing some running, but I hadn't been in a pool in quite some time," Bartholomew says. "And I didn't have a bike." He also didn't have $5,000 to, among other things, buy a plane ticket, buy a racing bike, and ship the bike and his other gear to Hawaii.

But before he could start raising money from family, friends, classmates, and sponsors, he had to complete an intermediate-distance triathlon. He chose the Bay State Triathlon in late August —barely two months before the Ironman—which featured a one-mile swim, a 38-mile bike ride, and a run of 9.5 miles. After spending most of the summer on a fellowship with the Indian Health Service (he attends DMS on an IHS scholarship), he borrowed a bike from a friend and started riding once or twice a week—at most 30 miles a time.

|

|

Michael Bartholomew (on the right in the lefthand photo) emerged from the swim leg of the Ironman Triathlon still feeling fresh, but by the time he crossed the finish line (above) he'd pushed himself to the limit. |

Rhythm: He returned to DMS early and called a colleague from his UVM rescue service days, someone who'd swum competitively in high school, for advice about that leg. "I thought at first, 'How hard can this be?" ' Bartholomew remembers. "My stamina was up to speed. Well, we swam one Monday in Burlington, and I think the lifeguard was watching me the whole time. We only swam half a mile, but it took me forever. I was gasping for air. I couldn't get a rhythm going." But he eventually worked himself up to a respectable 35-minute mile pace.

On the day of the Bay State event, he entered the water at 5:00 a.m. and emerged one mile and 32 minutes later. "I was a little queasy," he says. "It didn't feel like my feet were under me." But with a bike under him he felt better, and he ran fast enough to post a total time of 3 hours, 51 minutes, and to declare: "I want to go to Hawaii!"

But first, he had to ask DMS for a waiver to miss the beginning of classes and was relieved to hear: "Go out and do your best. Get back when you can."

Getting there: Then he had to get there. He got business sponsors, based on his record of community service. His father paid him $1,000 for help moving back to the ancestral Bartholomew dairy farm in western Vermont. And about 80 of his DMS classmates and teachers paid $10 each for tee-shirts designed by a local print shop. That allowed Bartholomew to buy a racing bike and equipment. For the remaining expenses, a bit over $2,000, "I maxed out all my credit cards."

Then he started training in earnest. Mornings, before class, he swam at a local pool, working up from one mile to two. After classes during the week, he bicycled a couple of hours up the New Hampshire side of the river to Lyme, then back down again on the Vermont side—about 25 miles. On weekends, he took longer rides—60 miles at first, later 80 or more. To prepare for the marathon, he ran about nine miles three or four times during the week and did a weekend run of up to 16 miles. "Some days were better than others," Bartholomew says. "One run, I really nailed it, then I moved on to the bike ride and struggled."

Rarely could friends join him for the struggle. "I was just going solo," he says. "You get to thinking, 'This is ridiculous. What am I doing? I need to study.' But once, when I was complaining, someone made the point, 'You're going to be out there all alone, anyway.'" Bartholomew stayed with this regimen until about three weeks before the Ironman —then threw himself into his studies and let his body rest.

Sleepless: Once in Hawaii, after getting over the jet lag, Bartholomew limited himself to an eight-mile run, a 40-mile bike ride, and a one-mile swim in the pool. Then, at 7:00 a.m. on race day, after a mostly sleepless night, he headed into the waves with 1,500 other participants and completed the first leg in an hour and 22 minutes.

"I looked at my watch, saw the time, and said, 'That can't be right,'" Bartholomew recalls. But he quickly decided, "I'll take it." After a shower and a change of clothes, he pedaled out of town in a conga line of bicyclists, with spectators cheering from both sides of the road—and immediately got a flat tire. Fortunately, a nearby gas station was able to pop on a new tire and send him right back out. Bartholomew settled into a good pace, struggled for a time with a headwind and an uphill, rode a lovely tailwind for a spell, then hit his first wall, less than 20 miles from the end of the bike leg.

"There was a three-mile stretch where I started to think, 'There are a lot better things I could be doing with my time right now.' If there was any point where I was going to drop out, that was it." But the feeling passed, and with 15 miles to go the course flattened out, enabling Bartholomew to complete the 112-mile ride in 6 hours, 51 minutes.

Spirits: But when he tried to change his shoes for the run, "I realized my hands didn't work. After all the time on the bike, my dexterity was just not there." Race volunteers were, however, and they helped him change his shoes and raised his spirits and his hydration level. For about six miles, on the way out of town, Bartholomew coasted on the cheers of spectators, including his girlfriend and her parents.

Then he headed out into the lava fields. "I once read a master's thesis a guy did in the 1980s on the body falling apart," Bartholomew says. "It said your body's telling you one thing, and your mind is telling you another. You always take that next step."

Next step: Now, for Michael Bartholomew, the next step is catching up with his classmates and figuring out how to spend the four years he owes the IHS when he graduates. In the meantime, he thinks sometimes about returning to those lava fields— and breaking 10 hours.

"I want to go back," he says. "I'm hooked now."

If you would like to offer any feedback about this article, we would welcome getting your comments at DartMed@Dartmouth.edu.