The admissions cycle: Will it be yes? Or no? Or an agonizing maybe?

This is the time of year when admissions officers nationwide, including those at Dartmouth Medical School, are sending out letters containing good news (an offer of admission), bad news (a regretful denial), or equivocal news (an agonizing waiting-list placement).

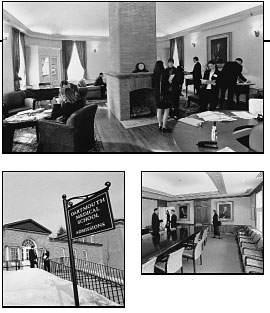

At DMS, those letters are going out this year from new quarters. Since last fall, the Admissions Office has been located in a renovated portion of the 1893 Mary Hitchcock Hospital building in Hanover. The new quarters offer more room, including a spacious lounge for interviewees; a historical aura more fitting for the nation's fourth-oldest medical school than the previous of- fices; and a gas fireplace by which applicants can warm their toes on frosty days.

Process: The admissions cycle begins even before the new class matriculates in mid-August. By that time, several thousand applications have already been received for the subsequent academic year. All applications originate with the centralized American Medical College Application Service (AMCAS). The national pool of medical school applicants fluctuates somewhat from year to year but has numbered more than 40,000 in each of the last five years, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Typically, one in six applicants nationally applies to Dartmouth. For the class that entered in the fall of 1999, roughly 6,200 candidates applied to DMS. The target size of the class varies slightly from year to year, depending on estimates of the number of clinical clerkships that will be available when the class reaches years three and four. The current first-year class numbers roughly 70 students— about 15 of whom are in a joint program with Brown University, to which the students will transfer after second year. These students experience a combination of rural and urban environments during their training. Also, several students each year—five in 1999—are admitted to a combined M.D.-Ph.D. program that usually consumes more than six years. (In addition, there are separate admissions processes for the applicants to DMS's Ph.D. programs in the biomedical sciences and to the master's and doctoral programs in the evaluative clinical sciences.)

|

|

The new but historic quarters for

DMS Admissions include a spacious

lounge and a conference room. |

The first cut in the pool handled by the Admissions Office is self-selected. As do many other schools, Dartmouth sends a shorter secondary application to each candidate. Many of those who have named Dartmouth on their AMCAS form do not complete the secondary application. By that mechanism, the pool of 6,200 AMCAS applicants is reduced to about 5,000.

Hopefuls: The next cut falls to four people: the faculty member who chairs the Admissions Committee, currently Associate Professor of Medicine Harold Friedman, M.D.; Director of Admissions Andrew Welch; and two assistant admissions officers. One of these four reads every completed application—more than 1,200 each. Each file contains a variety of material, including college grades, scores on the Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT), recommendations, and an essay. The topics of the essays range from the clever (one DMS applicant compared applying to medical school to her one and only bungee jump) to the poignant (many applicants write about triumphs of will over poverty, illness, racial or gender discrimination, or neglect). After this second cut, about 2,000 hopefuls are left.

Next, the 24-member Admissions Committee—which includes faculty, the three admissions officers, and a few students —divides itself into twomember subcommittees to make a third cut. Each subcommittee reviews a batch of 20 applications every two weeks over the course of several months, selecting roughly five applicants from each batch to be invited for an interview. Some committee members look most closely at a candidate's "numbers" (grades and MCAT scores), while others lean toward the intangible "other qualities" that also carry weight in admissions decisions at DMS. In the end, a balanced group of some 600 applicants remains under consideration.

Interviews: Those 600 are then invited to come to Hanover for an interview. Unlike the college admissions process—where interviews are almost always optional —medical school applicants who reach this stage of the process are required to travel to campus for an interview. Perhaps 500-plus of them actually schedule a visit.

Before the interstates linked Hanover to the rest of the world, but after the elimination of passenger train service, applicants discovered that the many charms of the Upper Valley did not include ease of access. There were rare instances of an applicant climbing into a cab at Boston's Logan Airport and requesting a ride to Hanover. Today, applicants are advised carefully on the now more numerous options for getting to Hanover, together with the relative costs.

On Tuesdays and Thursdays from October to April, the halls of DMS are thronged with immaculately suited young men and women. Each applicant is interviewed separately by two members of the Admissions Committee. Most committee members regard themselves as ambassadors of the institution and consider the interview as much a chance for the applicant to look at DMS as it is for DMS to look at the applicant.

Salvo: Committee members approach interviewing idiosyncratically. Some studiously avoid reading the application until after the interview, so they view the paper through the lens of a real person—perhaps startling interviewees who've slaved over their application with an opening salvo of, "So, where did you go to college?" Others peruse the files with care, noting topics that could use further amplification or on which to draw out a reticent applicant.

Longtime members of the Admissions Committee have many amusing anecdotes from "interview days." One recalls a very tall young woman who, when asked if she played basketball, replied, "No. Do you play miniature golf?" And neurologist Richard Nordgren, M.D., remembers a candidate who mentioned in her file that she liked to drive fast; when questioned, however, she played the interest down. Later that day, Nordgren was leaving the parking lot in his 12-year-old Subaru when a brand new Lexus paused beside him going the other way. The drivers both rolled down their windows, and Nordgren, looking up into leather-lined luxury, recognized the applicant. "No wonder you like to drive fast," he said. She explained at length that the car belonged to her father and was only borrowed for the occasion. Nordgren adds that she was admitted and had a distinguished career at DMS.

Earnest: When a sufficient number of applicants have been interviewed, usually by late October or early November, the work of the full committee begins in earnest. Committee meetings rarely last less than two hours, and there are at least two a month until the class is filled. Before each meeting, Friedman and Welch select a batch of candidates to be presented. The Admissions Office staff prepares a summary of each file. After each presentation, the two interviewers give their impressions, and then each member of the committee ranks the applicant. The committee's discussions are a microcosm of democracy at work. All segments of the institution are represented. There are basic scientists and clinicians. There are administrators and students. There are advocates for family medicine and advocates for research. No member shies away from expressing an opinion.

Like any slice of Americana, the applicant pool includes a few scoundrels. The committee has detected "doctored" transcripts, forged recommendations, and exaggerated claims about activities. Most are caught before an offer of admission is made, but in a few cases an acceptance has been withdrawn.

Spaces: The committee's work keeps rolling forward as the months pass. Over the years, the School's experience has been that acceptances have to be offered to about twice as many applicants as there are positions available in the entering class. The spring is often cuticle-chewing time, when the committee may want to issue more acceptances than the available spaces permit. But if the number of acceptances seems a little low to fill the class, some offers can be extended to those on the waiting list, who have been doing their own cuticle-chewing. On rare occasions in the past, if there is a very late withdrawal, an applicant may receive a call in August saying, "How would you like to start at Dartmouth Medical School tomorrow?"

And by then, the next year's cycle is already well underway, as the Admissions Committee once again works to winnow from more than 6,000 highly qualified applicants another class of talented, articulate, bright, hardworking, caring doctors-to-be.

Roger P. Smith, Ph.D.

If you would like to offer any feedback about this article, we would welcome getting your comments at DartMed@Dartmouth.edu.