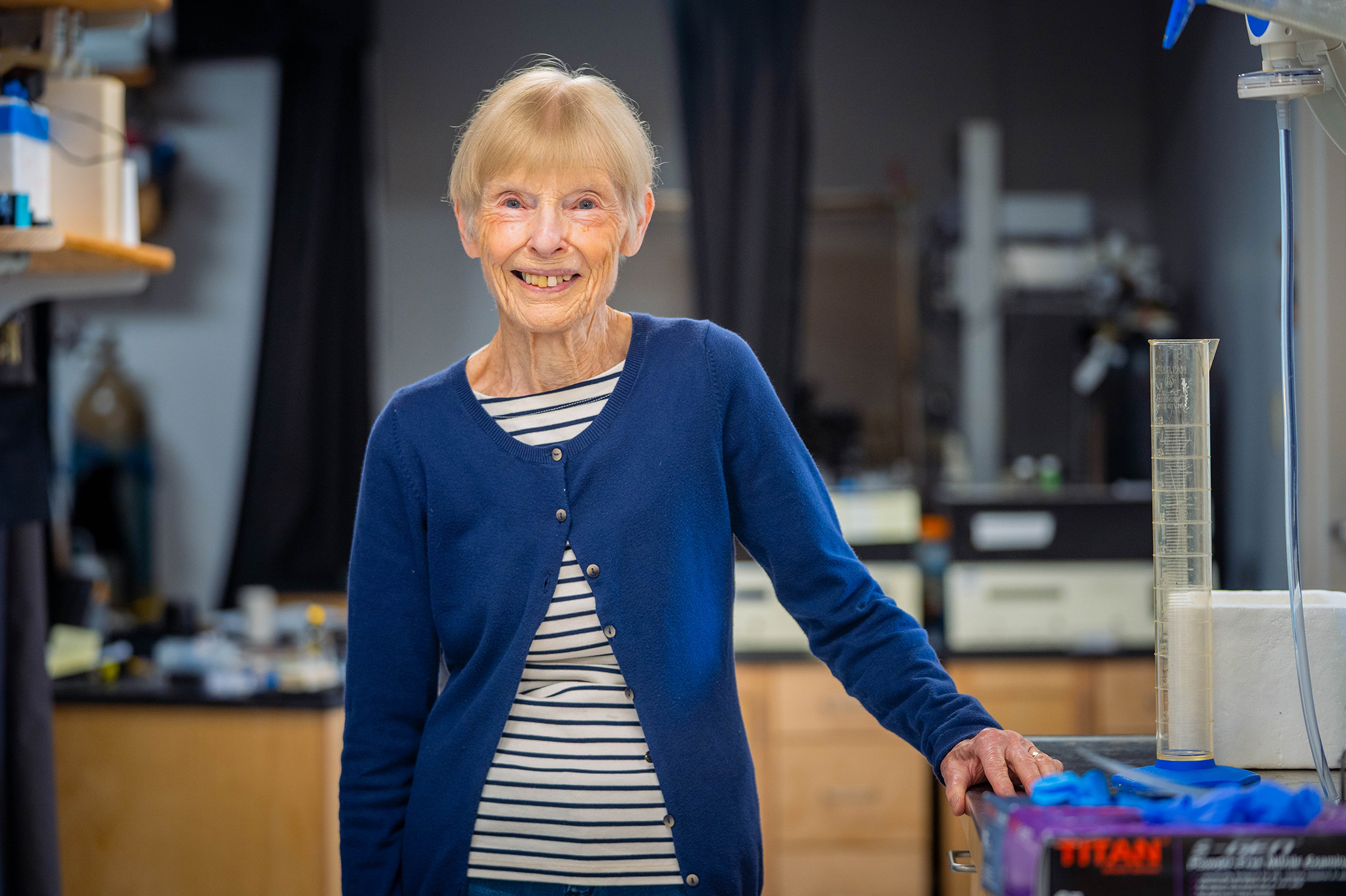

Valerie Anne Galton, PhD, Professor Emerita of Physiology and Neurobiology at the Geisel School of Medicine, has made significant contributions to the advancement of our understanding of thyroid physiology and hormone economy, including the roles of the iodothyronine deiodinases in the regulation of intracellular thyroid hormone content and thyroid hormone action during development.

A member of the medical school’s faculty for 60 years, Galton has been, and remains, a renowned leader in research related to thyroid hormone metabolism. Her recent work centers on testing the hypothesis that T4, the major circulating thyroid hormone, is more than a pro-hormone.

In 1960 when Geisel, then Dartmouth Medical School, offered a two-year program in the basic medical sciences, Dean S. Marsh Tenney, MD, was in the early stage of “re-founding” the school—expanding facilities, seeking faculty, and establishing a physiology department.

At that time, Galton, and her husband Michael, were in Boston for what they thought would be two years before returning to England. Galton was a post-doc with the late Sidney Ingbar, MD, a well-known authority on the thyroid gland and its diseases, and her husband, an obstetrician, worked at the Boston Lying-in Hospital (now part of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital).

A surprising invitation changed the course of their lives.

Kurt Benirschke, MD, the late pathologist and expert on the placenta and human reproduction, with whom Michael had been collaborating in a research project, at the Lying-in Hospital, left Boston in 1960 for Hanover to become chair of pathology at Dartmouth. He invited Michael to join his lab. When the Galtons traveled to the Upper Valley to discuss the prospective job with Benirschke, Michael was prepared to accept the offer, but only “if there was a position for Val as well.”

Benirschke was sure there would be and urged her to meet with Tenney, who also chaired the physiology department. At their meeting, Tenney was very open to Galton joining the department.

Later, when Galton and Tenney met to talk about her research interests, he mentioned that the physiology department would welcome an endocrinologist who could participate in teaching the endocrine course—the late Allan Munck PhD, a biophysicist, was teaching the course by himself. Was she interested? Yes. Tenney said he could offer her a small salary, but she would need to secure research funds.

“We talked about my current research and applying for funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). He asked me to write out a description of my project so his secretary could type it on the grant application that I would sign, and she would then submit it to NIH,” Galton recalls. “I did it in one afternoon and the project was funded. Clearly it was a very different time—the last grant application I submitted to NIH took me six months to complete.”

In mid-1961 when Galton and her husband officially arrived at Dartmouth, the medical sciences building, now known as Remsen, was newly completed. Galton happily established her lab in the new building near the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital.

She and Munck, a Professor Emeritus of Physiology and Neurobiology until his death in 2016, further developed the medical school’s endocrine course and eventually Galton became the course director. She also helped the Graduate Program in Physiology get off the ground and was very involved in the PhD and MD-PhD programs throughout her time at the medical school.

Immersed in her work, enjoying the comradery and respect of her colleagues, she and her husband left for a sabbatical in Mexico in late 1967. Her objective was to study thyroid hormone economy in patients with a Hydatidiform mole, a product of conception that is not a fetus but a benign tumor. These patients have exceptionally high circulating levels of thyroid hormone but exhibit few if any symptoms of hyperthyroidism. Unlike the U.S., Mexico sees several such patients per year. Galton’s husband, who was interested in becoming board certified in the U.S. so he could carry out both research and clinical practice as a physician-scientist, had arranged for a position at the Cleveland Clinic that would allow him to work and prepare for the boards when he returned from Mexico. Galton had accepted a job at Case Western Reserve Medical School in Cleveland.

Tragedy struck. During their trip home from Mexico, Michael was hit by a speeding car in Texas and died from his injuries.

She returned to Hanover as a single parent of two young boys. “Everyone was very helpful and supportive when I returned,” she says. Soon thereafter, Tenney approached Galton with an offer to remain in the physiology department—consensus among the faculty was unanimous. “He wanted me to think about it, but I looked at him and said, ‘I don’t have to think about it. I’m very happy here and want to stay.’”

She furthered her research and continued teaching and in 1975 she was promoted to full professor with tenure.

William C. Torrey, MD, D ’80, the Raymond Sobel Professor of Psychiatry and interim chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Dartmouth-Hitchcock and Geisel, worked in Galton’s lab during his senior year at Dartmouth College.

“While Dr. Galton advanced science, she also advanced the careers of generations of student learners,” Torrey recalls. “She took me under her wing to work in her lab when I was an undergrad in 1980. Her generous and respectful approach toward me reinforced my interest in pursuing a career in medicine. Now after more than 40 years, she is still working alongside me here at Geisel!”

Galton has witnessed many changes during her 60 years at the medical school, including the implementation of a three- then four-year medical education program, recruitment of additional endocrinologists, the increasing enrollment of women, and the physical expansion of the medical school’s campus. In the early 2000s, changes in the medical curriculum and how courses were taught were implemented, including a shift to fewer lectures and more small group learning exercises, a switch that she and her fellow endocrinologists, with the help of Donald St. Germain, MD, had already made in the early 1980s.

While these changes were gradual, for Galton the most striking was the rate at which women were, and are, being admitted to the medical school. When she arrived at Dartmouth in 1961 there were a few female students enrolled in the medical school. Today, the ratio of women to men is more than fifty percent.

It may be tempting to judge the past through a contemporary lens, but Galton says, “There should be no judgements—I have no regrets. It’s important to be open to change and to stop always being critical. Dartmouth is a close, supportive community and I’ve enjoyed my entire time here. I’ve been treated extremely well throughout my career.”

Though Galton retired from teaching in 2017, she still has lab space through the generosity of Hermes Yeh, PhD, the William W. Brown Professor of Physiology and Neurobiology, and remains an active researcher. Earlier this year, the American Thyroid Association established the Valerie Anne Galton Distinguished Lectureship Award recognizing her remarkable scientific accomplishments and significant contributions to the advancement of clinical knowledge of thyroid conditions.

It’s the organization’s first lectureship named in honor of a woman.