DHMC discovers that recycling makes good sense and good cents

The logic is inescapable, according to James Varnum, president of Mary Hitchcock Hospital: "Hospitals across the country each day work hard at improving health in their communities, yet they generate two million tons of waste a year, some of it very toxic. If we pollute our neighborhoods with poor waste-management practices, we contribute to the very health problems we're committed to curing."

Awards: Back in 1990, the focus of DHMC's environmental programs was on regulatory compliance. Since then, it's expanded from meeting minimum standards to being one of the best hospital waste-management and recycling programs in the country. Proof lies in three major awards in less than two years:

- A few months ago, in Concord, N.H., DHMC was presented with the 1999 Governor's Award for Pollution Prevention, for a yard-long list of "pollution prevention successes."

- In May of 1999, at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., DHMC was given the "Making Medicine Mercury- Free" Award by Health Care Without Harm, which calls itself "the campaign for environmentally responsible health care."

- And on Earth Day 1998, in Boston, DHMC was the only hospital to receive the EPA's annual Regional Environmental Award, for being "an outstanding environmental advocate" and applying what the EPA's John DeVillars called "good old Yankee ingenuity in addressing many of New England's most pressing and complex problems."

All new: Things were different before DHMC's 1991 move to the Lebanon campus, says environmental programs coordinator Laura Brannen. At the old Hanover site, with each department managing its own hazardous materials, "all sorts of nightmarish things could accumulate under sinks, in closets, in cabinets. Moving to the new Medical Center presented us with a wonderful opportunity to start fresh, and design and install all new systems."

For example, construction plans called for a new medical waste incinerator, but "no one knew how much waste we generated: how much hazardous chemical waste, infectious waste, waste to be sterilized, or even how much solid waste went to the landfill." Enter consultant Victoria Jas, hired to do a detailed waste audit. Today, Jas is still at DHMC, as manager of biosafety and environmental programs, joining Brannen, who handles DHMC's hugely successful recycling program and pollution-prevention initiatives, and Mike Brown, a hazardous materials technician. Collectively, the three deserve much of the credit for DHMC's awardwinning performance.

|

|

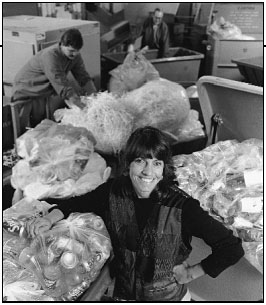

Laura Brannen's job involves making sure that as much of DHMC's waste

stream as possible ends up in recycling bags and bins—not in the landfill. |

Most hospitals incinerate their solid waste. Yet despite the clean-air legislation of the past two decades, almost 70% of hospital incinerators have no pollution- control devices. In an era when nonreusable plastic instruments constitute a large part of hospital waste, incineration poses a potential public health hazard because it releases two major toxins: dioxin, the world's deadliest known carcinogen, from plastics containing polyvinyl chloride (PVC); and mercury from instruments like thermometers and blood-pressure devices. Although one thermometer contains only 0.003 pounds of mercury, that's sufficient to necessitate public warnings about consumption of fish in a 30-acre lake. Federal studies have con- firmed that incineration is a major reason these highly toxic contaminants find their way into the nation's food supply, ending up in startling amounts even in processed baby food.

A survey of the nation's hospitals done by the nonprofit, Washington-based Environmental Working Group (EWG) showed that over 40% of the top 50 hospitals polled were still incinerating waste that could be disposed of by a safer method. Only one in five had programs to reduce purchases of plastic goods containing PVC.

Irony: And ironically, even though the EWG survey found that four of five hospitals surveyed had mercury reduction programs, nearly half were still buying mercury thermometers and over half were still purchasing mercury blood-pressure monitors. DHMC, however, has replaced nearly all mercury-containing devices—thermometers, blood-pressure devices, electrical switches, and thermostats—with non-mercury alternatives.

In addition, DHMC now has two large autoclaves that sterilize medical waste with superheated steam before it's incinerated. (Chemotherapy and pathology waste—a small percentage of the total—is sent to a commercial incinerator employing even more sophisticated pollutioncontrol measures.)

Since 1996, through intensive employee-education, DHMC has reduced the amount of trash sent to the autoclaves from 35% to 12% of total waste. DHMC now recycles 30% of its trash, including materials like grease, linens, shrink-wrap, fluorescent bulbs, x-ray film, and silver. Infectious waste—whose disposal is both costly and labor-intensive —has been reduced from 36% to 14% of the total. In addition, Jas is overseeing a threeyear effort to significantly reduce —and to ultimately eliminate —the use of ethylene oxide, a hazardous gas used widely in the sterilization of instruments. "It's all," says Brannen, "a matter of changing the culture.

"Environmental programs pay for themselves," she adds. "But although any hospital can hire somebody to look at their waste-handling situation, a thorough job can't be done without top-down commitment to the enterprise. Our waste costs have gone down because of the statement of environmental principles approved by the board of trustees and senior leadership."

Implications: "Every time a hospital employee makes a decision about where to throw trash, there are cost implications," Brannen explains. "A 30% recycling rate means well over 3,000 pounds of material a day doesn't go to the landfill. Naturally, when recycling markets are strong, there are stronger financial incentives to recycle. But even when they're sluggish, recycling is still landfill cost-avoidance." Similarly, minimizing infectious waste (which is six times as costly to dispose of as ordinary waste) saves hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.

Evangelism: "It's our job to create a general awareness of how really easy these principles are to put into practice," she says. "Doctors aren't taught a thing about environmental health in medical school; neither are nurses. For the past two years, we've been meeting with incoming residents during their June orientation, briefing them on our programs, their role, and how this all ties in with environmental and human health. Regardless if they stay here or go on someplace else later, we hope they'll take this philosophy with them. . . . It's evangelism, really."

Brannen preaches this gospel all over the country, as does MHMH President Varnum. In a recent EPA-funded videotape, he encourages hospitals to follow DHMC's lead and "be real environmental stewards in their communities . . . meeting the highest environmental standards of all, while still providing the highest-quality health care."

"That's not to say we've figured it all out yet," Brannen cautions. "If you followed our dump truck to the landfill . . . you'd still see newspaper in there and glass and aluminum. But we're making a difference."

Mary Daubenspeck

If you would like to offer any feedback about this article, we would welcome getting your comments at DartMed@Dartmouth.edu.