Form & Function

Optimal space for science

The comments below by researchers regarding the benefits of open-space scientific labs like those in Dartmouth's Cancer Center addition were excerpted from interviews conducted by Dartmouth Medicine Associate Editor Laura Carter.

Charles Brenner, Ph.D.

Brenner, codirector of the Cancer Mechanisms Research Program, uses genetics, protein biochemistry, and x-ray crystallography to dissect the cellular functions of enzymes that play a role in cancer.

The room where I did my graduate work had six benches and six individuals from six different laboratories, so there was a lot of cross-pollination.

Medicine is such a complicated problem. I might identify a molecular target for genotype-specific treatment of a particular type of tumor, and work on the enzymology of that molecule and potentially obtain some lead compounds to inhibit a particular enzyme. But if I don't consider the cellular, organ, and physiological effects of inhibiting that target in a living animal, in a living cancer patient, then ultimately that drug would fail at some point before it gets to the clinic. The benefit of having researchers in the Cancer Mechanisms Program, the Immunology Program, the Molecular Therapeutics Program, and other programs in this building is that we talk to each other about our research interests and we try to consider in advance the rate-limiting steps to improve cancer care.

Randolph Noelle, Ph.D.

Codirector of the Immunology and Cancer Immunotherapy Research Program, Noelle does research on CD40 cell-signaling.

I see tremendous advantages to the open labs. The architectural design and engineering is superb. It's bright, it's cheery, it's lively. That has a very significant impact on doing science. Science is a chore if you're in unattractive sur-roundings. Everything you can do to improve your environment is very worthwhile.

And I don't see any disadvantages. The disadvantage I had perceived is not one. Each lab has its own personality. We have a rather chaotic, loud, obnoxious personality as a lab, and I thought the open space would dampen individualism. It doesn't. It's so well-engineered that one group can express their personalities without interfering with other groups.

We are already talking about brain tumor models with Mark Israel. My postdocs talk to his postdocs about applying our immunology expertise to his brain tumor expertise. That wouldn't have happened as quickly if our people weren't talking to one another. It's not just me. Actually, I'm probably the least important. It's our people—our postdocs and graduate students—talking to one another. It's sitting in the coffee room. It's people getting to know one another—having casual contact—that leads to really important scientific relationships.

Michael Cole, Ph.D.

Cole, a member of the Cancer Mechanisms Research Program, studies genetic events leading to cell proliferation and cancer. Among his collaborators is geneticist Steven Fiering, Ph.D.

The person I've had more contact with so far is Steve Fiering, who is a mouse geneticist mainly. I'm interested in chromosomes in gene regulation, in oncogenesis. Steve has been working for a long time on bigger questions of chromatin structure and how long-range interactions can control gene regulation. That's exactly the kind of thing that I've been working on for a long time. We all put in our dibs for who we wanted to be next to, and he ended up being the one who was a good pairing.

Christopher Lowrey, M.D.

Codirector of the Cancer Mechanisms Research Program, Lowrey studies how cancer subverts normal cell growth and behavior.

I just happened to bump into Steve Fiering in the hall, and we started talking about a project that we're doing together. We're studying how genes get turned on and off in blood cells. We're working on a brand new system that no one else is using, so we have to work out some things from the ground level. For the first time, our offices are right next to each other, our labs are right next to each other. Even in the week that we've been together it's made a difference already.

Kenneth Meehan, M.D.

Meehan, director of the Bone Marrow Transplant Program and a member of the Immunology and Cancer Immunotherapy Research Program, works on Interleukin-2 therapy for myeloma.

I like the open-air atmosphere. It lends itself to creativity. We are finding that there's a lot of molecular similarity between tumors— that you might be able to use the same drug to treat different tumors based on cell mechanisms. In an environment like this, hopefully a lot of clinicians will be in tune to opening up their horizons and saying, "Let's not use just the old standard chemotherapy, let's try some of these new drugs and see if they work, based on molecular mechanisms."

William Kinlaw III, M.D.

A member of the Cancer Mechanisms Research Program, Kinlaw does research on a protein called S14.

I really liked the group that was in my immediate vicinity up in Borwell. But over the years, my research changed so that slowly I morphed into somebody who had very little in common in terms of research with the folks that I was in the midst of.

Everybody is showing a really good heart with this move. For people who are used to having their own little bailiwick, their own lab space, it's a change to be sharing everything. It raises some obvious possibilities for friction and territorialism. But I haven't seen any of that—not any—which surprised me. I was even worried that I might start showing it, especially with sharing my tissue culture. But this obviously seems a more efficient way to do things. It seems like it's really going to offer a lot more possibilities for informal interactions that are productive.

E. Robert Greenberg, M.D.

A member of the Epidemiology and Chemoprevention Research Program, Greenberg is also former director of the Cancer Center. He works on the national cancer registry program of the Centers for Disease Control.

You don't want people going off into their offices like turtles. When you have nice open spaces, people will take the opportunity to sit down and discuss ideas. It adds to the interconnectedness, and the Cancer Center is an organization that requires interconnectedness— it's at the heart of what the center is. Form follows function, if you will.

Tim Ahles, Ph.D.

A member of the Cancer Control Research Program, Ahles studies the cognitive effects of chemotherapy and works on improving palliative care and the care of chronic illnesses.

When we were back in Hanover, basic science people were in labs that were in different buildings; paths did not cross that often. I think by moving out here, and with the new Cancer Center space, people are brought into closer proximity. It's become much easier to collaborate.

|

|

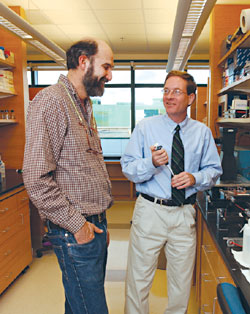

Above: Charles Brenner, right; Pawel Bieganowski,

center; and Huan Liu, left, strategize at

a whiteboard. Below: Steve Fiering, left, and

Chris Lowrey, right, now have adjacent labs. |

|

Alan Eastman, Ph.D.

Eastman is codirector of the Molecular Therapeutics Research Program. He studies novel molecular targets and collaborates with oncologist Raymond Perez, M.D., on developing new drug strategies to treat cancer.

Ray Perez and I are actually going to integrate our research meetings. We're going to be sharing a tremendous amount of equipment and an office complex as well. The work that we do is completely different on a scientific basis. I'm doing preclinical development, looking for novel molecular targets— strategies for therapies. But that's meaningless if I can't put them into a patient.

I see the new space as facilitating far more interaction with everybody. You talk to people you meet in the corridor. You talk to people you meet at the coffeepot. Science is communication. You have to learn to communicate it with other people. You have to listen to them as well. If you're put in a corner to do your own experiment, and are not reading any of the literature, you could answer your question in about four or five years' time maybe, but was it worth doing? By then, maybe somebody scooped you four years ago and you didn't know it. So communication is absolutely critical.

Nathan Watson

The manager of Cancer Center Director Mark Israel's lab, Watson oversees research involving pediatric brain tumors.

Your average researcher is very focused. It's wonderful—you turn out great research. But with people who are innately like that, how do you get them to share ideas? I'm a fairly outgoing person—what about somebody who's not? They're not going to feel comfortable knocking on somebody's door and going into a room.