Between the Front and Doctor Bowler

By Constance E. Putnam

During World War II, although DMS graduates and Hitchcock staff members were scattered far and wide in the service, they kept in remarkably close touch with Hanover. A stream of letters, notes, and cards flowed from barracks and battleships around the globe back to the desk of Dr. John Bowler—and vice versa.

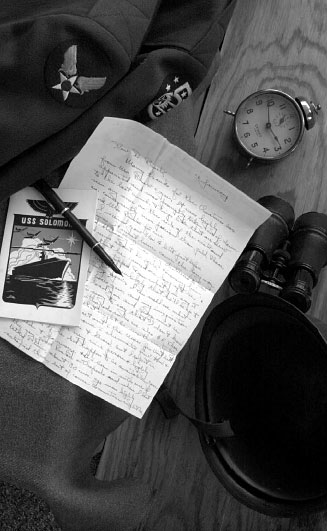

The photographs on these and the following

two pages depict some of the actual letters

sent to Dr. Bowler; the scenes are re-creations

using period and reproduction artifacts.

All photos: Jon Gilbert Fox

'I really appreciated your card and thought that Paul Sample did a very nice job on the winter scene at Dartmouth." So wrote Santino "Tino" Lando, DMS '38, in mid-January of 1943 from a U.S. Navy mobile hospital somewhere south of the equator. What had turned Lando's thoughts from the battle front to the home front was a holiday card picturing snowy New England that he'd received from Dr. John Bowler, who headed both the Hitchcock Clinic and Dartmouth Medical School during the war years.

"Dear Doctor Bowler," wrote housestaff alumnus Roland Lapointe that same month. "Was very happy to receive a Christmas card from you . . . with all the interesting news. I am now in North Africa and am getting along nicely."

These two notes are among numerous letters written to Bowler by former Dartmouth students and Hitchcock interns and staff members. The geographic range of Bowler's correspondents is impressive. "I suspect you hear from everyone everyplace, these days, but India claims my talents for the time being," was the way Ralph Keyes, DMS '34, began a long letter in August of 1944.

The volume of the correspondence is also astonishing —a testament to the culture of letter-writing that prevailed 60 years ago, before today's easy e-mail communications and global phone connections. Not only did legions of soldiers and sailors care about keeping in touch with Bowler, but Bowler clearly responded in kind, while sustaining Hanover's war-depleted medical enterprise. Only the letters written to Bowler have survived, but it is apparent that many also went out from his pen. [For more about Bowler, see page 28.]

Bowler obviously appreciated hearing from his former charges and colleagues, as evidenced by the fact that he saved this touching cache of communications. Likewise, his letters clearly meant a lot to the men (and a few women) who received them, even when they did not respond promptly. Tino Lando began a September 1942 missive thus: "The prodigal finally buckles down to write you after having had it planned for such a long time." And Ralph Hunter, DMS '32 and a longtime Clinic colleague of Bowler's, wrote in late March of 1943 from a hospital in Northern Ireland: "I hope you haven't thought from my long and unpardonable silence that I have forgotten you and all that I left behind, or that I'm unmindful or ungrateful for all that you have done for me. That includes your letters [and] your very thoughtful remembrance at Christmastime, now well alight in my favorite pipe."

The theme of gratitude for holiday remembrances occurs with considerable frequency, making one wonder how Bowler and his wife managed to send off so many packages, notes, and cards. Roland Lapointe, still in North Africa in late 1943, celebrated Christmas early: "Dear Dr. and Mrs. Bowler," he wrote on November 28. "Received your Christmas package and it was a very happy and pleasant surprise. . . . It was very delicious and also a rare treat here in North Africa." Frank Connell, a DMS faculty member from 1935 to 1954, also got an early package that December (though it took him until mid-January to send thanks). "Dear Jack and Dolly," he began, attesting to a closer relationship with the Bowlers than some others had. "Your nice Christmas box arrived safely and early. I was one of the few who held his few packages until Christmas. I broke yours out Christmas Eve, and the other two boys I was living with at the time joined me in fruitcake and brandy before we turned in for the night. That was probably a bad combination for the stomach, but it tasted mighty good and helped for a minute to make us feel a little nearer home and the Xmas trees we would have been trimming had it been ordinary times."

Even packages that didn't arrive until after Christmas were welcome. On December 27, 1943, Evelyn Vadney—a Hitchcock nurse serving with the Army in India—received a "lovely box of goodies . . . in good condition. It was enjoyed by us all, as food from home tastes so much better than our 'lend-lease' rations." That New Year's Eve, 1939 DMS alumnus John Godfrey wrote in a similar vein: "I just got your Christmas gift and card yesterday —it was swell of you to think of me. The cake and other delicacies struck right home, because, while our rations have plenty of calories and vitamins, no one would call it a varied diet. I figure I've eaten between one and a half and two long tons of Spam since I've been here."

But holiday packages were not the only things for which Bowler's correspondents were grateful. "For some weeks now," wrote housestaff alumnus Robert Foley from Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania in August 1943, "I have intended to write you expressing my appreciation of the part you played in making possible my pleasant postgraduate year in Hanover." Walter Chase, DMS '37, wrote in May 1944 from England, asking for details of his mother's treatment at Mary Hitchcock Hospital. Two months later he wrote again, from France: "Thank you very much for your prompt letter about my mother. . . . Am very much relieved that you found nothing seriously wrong with her."

The letters indicate that the men and women who had gone out from Hanover were confident Bowler was an interested recipient of their news, personal and otherwise. John Hardham, DMS '37, wrote in May 1943 from Fort Benning, Ga.: "I must explain, before I go further, that these snapshots show my wife and our almost-six-month-old daughter, Ann. The latter is now an accomplished wiggleworm and zwieback-buster, a source of great amusement and pride to her parents." In February 1944, Jesse Galt, DMS '37, cheerfully reported to Bowler: "As you probably know by now, Anne is pregnant . . . . We are both happy."

|

Letters often mentioned the constraints imposed by censors. Housestaff alumnus A.E. "Mac" Mac- Neill, a surgeon with the 72nd Fighter Wing, wrote just before Christmas 1943: "Some day I hope that I can . . . tell you some of the experiences which I have had in the psychiatric field—when they are no longer military secrets." And F.C. "Corb" Moister, DMS '38, penned the following note in July of 1945: "I . . . am sincerely looking forward to relating a few of the numerous happenings that have occurred, in person, sometime in the future."

The longing for home is palpable in many of the letters. "Good old Dartmouth," mused John Feltner, DMS '33, from North Africa in December 1942. "How I'll miss New Hampshire this winter." That same month, Radford Tanzer, a 1925 College graduate and a longtime Clinic staff member, wrote plaintively from Utah: "Thanks a lot for your recent letter, with the aroma of home." Hitchcock nurse Pauline Murphy, a lieutenant at the 9th General Hospital, lamented in December 1944: "I surely do miss the good and interesting surgery of Hanover, and I hope the offer to return when I come home still holds. Truly, we get tired of secondary closures, hernias, etc." Clinic member Henry Heyl, who did indeed return to Hanover, wrote likewise in June 1943: "You can't know, or maybe you do, how constantly my thoughts wander back to Hanover and the Clinic. That's my home, and I hope nothing will ever happen to prevent my being there, living and working with you all."

No doubt the nostalgia was sparked in part by circumstances that would have made almost any former life seem idyllic. Richard Storrs, DMS '40, wrote from aboard the U.S.S. Ross in July 1944: "This isolated medical practice is probably very good for me—having to make all my own decisions without advice—but seems pretty rough at times. I've recently had two psychiatric cases whom it was a great relief to transfer. One walked in his sleep and went overboard around 2:00 a.m.—but luckily was picked up all right. The other I never could make a definite diagnosis, beyond probable hysteria, but it took five men, a canvas restraint, and so[dium] pent[obarbital] to keep him quiet during the great part of two days. . . . I'd give most anything to be back at MHMH now—but realize I was very lucky to be there as long as I was."

Other postings apparently offered less excitement. In October of 1943, Dwight Parkinson, DMS '39, professed to being bored at Camp Adair in Oregon. He also fretted over lost opportunities in Hanover. "How I appreciate those precious few weeks of surgery I had with Dr. Gile. . . . Unless I'm an old man after this is all over, I certainly hope I can come back there and finish out my internship. . . . The longer I'm here, the more I realize how darned little I know."

By February of 1945, however, Parkinson was in Germany and no longer complaining of boredom: "All my men are heroes for my money," he wrote. "Most of them have been decorated, many of them twice or more. According to the book, the wounded are brought to the battalion aid station, bandaged, given morphine and plasma, and sent right back to the clearing stations and hospitals. . . . No situation is similar to any previous one. We are constantly confronted with something for which there is no precedent. . . . My sincere wish that I had in- finitely more training mounts each day. There is no wound or combination of wounds, I believe, that has not passed through our aid station."

Others had it even worse. Some of the most harrowing tales were told by housestaff alumnus John Grindlay, who figured in a July 20, 1942, article in Time magazine—Gordon Seagrave's "Surgeon in Burma." A few weeks prior to that, in June, Grindlay had detailed for Bowler his experiences both before and after being assigned to General Joseph Stilwell's staff as an assistant surgeon. Traveling in free China during the winter by jeep and truck on the Burma Road and "operating sometimes in bare hospitals," Grindlay "never did get used to operating in freezing, raw cold."

Soon after he joined Stilwell, "the war in Burma opened up. The wounds we saw were horrible," he wrote, "usually multiple and usually with at least one compound fracture. About 75% were extremity wounds, 10% each head and abdomen, and 5% penetrating chest wounds. We had 80 to 160 of these seriously wounded cases a day, most of them coming in at night (due to enemy air activity). I did a good half of the cases and for five days all of them. We had six operating tables. And we not only brought the cases in from the front but got them to hospital ship or evacuation hospital after operation and a one- to two-day recovery period. The answer to your amazement is that we had a marvelous group of workers—the 19 hill-tribe Burmese nurses that Seagrave had trained, the seven Friends Ambulance Unit English lads, and six other Burmese and Indian lads who did everything. We had also to get our own supplies, do our cooking and laundry, etc. And to these difficulties was added the daily bombing and strafing all about us. I'll leave descriptions of this, of destruction and misery, to those who write better than I. . . .

|

"You will be more interested in hearing of how the cases came along. We seldom lost any of the compound fractures—using entirely the debridement, vaseline gauze pack, powder sulfanilamide, plaster method. We lost about half the amputations and abdominal cases [but] almost no chest cases (the really bad ones died before they got to us and all we ever did was aspirate blood and debride the surface wound) and almost no head cases. The trouble with the amputations and abdomens was that we never got our cases under 12 hours, and some were 48 hours old; also that we had no way to combat shock—no blood or plasma. We just didn't have it—there wasn't time and there were no donors or refrigerators, and the temperature was usually close to 120*. Our head cases were all shell and bullet wounds, and all we did was debride scalp and bone—in effect a decompression—and drain; we seldom got the foreign body."

Many of Bowler's correspondents expressed appreciation for their training in Hanover. Tino Lando wrote in November 1942 that he felt "very lucky to have such a well-rounded service, to work with such a swell group of men. . . . I had a grand two years there. . . . I can say that the deepest and fondest friendships I possess are found in Hanover and the Hitchcock." Franklin "Bud" Lynch, DMS '41, struck a similar note from "somewhere in England" in April 1944: "I want to express my appreciation for the opportunity I had to intern at MHMH. I am very sorry I could not stay longer."

Bowler must have been gratified by such remarks. He must also have been pleased by how frequently his correspondents prefaced observations about their own wartime service by saying they knew how hard he and others still in Hanover were working. The chief basis for such knowledge was the "Hitchcock Highlights" newsletter, sent out to all former interns and residents. The first issue, in June 1943, began: "Herewith, the 'Hitchcock Highlights' makes its modest bow before a surprised and pleased (we hope) audience." Readers also got an idea what life back in Hanover was like when - with an affectionate personification of the Hospital - they were informed that "Mary has been having a very active time of it and has been bulging at all her seams like an overstuffed dowager, the problem being to squeeze into our 164 beds the 200 or so patients who are clamoring for admission most of the time."

Those in the service loved the news from home. Dwight Parkinson enthused from Oregon: "'Hitchcock Highlights' is extremely interesting to me out here, as I imagine it is to all the others who are scattered around at various out-of-the-way locations." Housestaff alumnus Madison "Joe" Brown wrote in June 1944, "I have enjoyed the 'Hitchcock Highlights' very much and want to thank you folks for keeping me on the mailing list!" Another former resident, Renwick Caldwell, reported in February of that year that the "latest issue of the 'Highlights' arrived last Saturday, and I sat down after supper and read it from start to finish." And from England, DMS grad Walter Chase pleaded in May 1944, "Do not forget me when the next issue of 'Highlights' is printed."

Given the intensity of the work at Hitchcock, and the long hours that the stretched-thin staff had to work, Bowler's efforts to stay in touch were quite amazing. In January 1944, John Feltner poignantly summed up, as well as anyone could have, the impact Bowler had on the spirits of those in the service: "Your welcome Christmas card was very appreciated. To be frank, I do receive a definite boost of morale and an incentive to do my best professionally from contacts with and attention of men whom I have admired for their professional standards . . .

"January in Africa," he went on, "[has] many clear days - comfortable when the sun is out. Still, I've a great nostalgia for snow and ice and would like to glide around Occom Pond on skates or see Hanover chimneys smoking peacefully in the winter air from the high slopes of Balch Hill. Thank you again for your Christmas note - and please give my sincerest regards to all those who are carrying on the heavier home front burdens."

Medical historian Constance Putnam's work has appeared in Dartmouth Medicine many times. In fact, she made another contribution to this issue—a feature about the history of the Hitchcock Clinic (see page 28). She also wrote in the Summer 2002 issue about the medicolegal activities of DMS's founder, Nathan Smith. She holds a Ph.D. from Tufts University and is the coauthor (with Dr. Oliver Hayward, DMS '32) of Improve, Perfect, and Perpetuate: Dr. Nathan Smith and Early American Medical Education. She is greatly indebted to Dr. Bowler's daughters —Patsy Bowler Leggat and Janet Bowler Fitzgibbons—for the generous loan of two boxes filled with their father's papers, including the letters that are quoted in this article. Some of the punctuation and capitalization in the passages excerpted here from those letters have been modified for ease of comprehension.