Viewpoint

A link to the living

By Patsy Garlan

You can imagine how startling it was when my daughter the medical student inquired, "Would you like to see my cadaver?" A glance at her eager young face filled with cheerful expectancy made me soften the fervor of my denial to "Oh, no, darling, no—I don't think so. No. No."

Ye gods. But then I thought better of my negative reaction. How often does a person, a layperson, have an opportunity like this— to look inside the body of another human being? You'll be forever sorry if you pass up this chance, I thought to myself.

|

|

She had been working on a section of colon, I think it was.

I was astonished to see that our bodies' essential parts are all

neatly organized, many in their own little membranes—like

plastic-wrapped leftovers in a well-maintained refrigerator. |

I glanced at her again. She was waiting for me to come round. As she always did—the way all kids do. "Well," I said, "what would it be like?"

Queasiness: So off we went, into the warm dusk of the New Hampshire evening. I found myself fighting my apprehension and hoping that I would be able to control my queasiness.

As we descended the stairs heading deep, deep into the cavernous basement of the medical-school building where the anatomy lab was housed, she began to prepare me. "It will be cold," she explained, "because . . . you know. And there will be a smell of formaldehyde," she added. "Don't mind it," she said, "you'll get used to it."

We entered the dimly lit lab. I want to say that we crossed a threshold, like Dante following his guide and mentor Virgil into the underworld —although no sign above the entrance warned "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here." And although she never took my hand, I felt as if she had.

We wound our way among the sleek gurneys with their sheetshrouded burdens. Not another soul breathed in that vast space. The smell of formaldehyde was an assault. The silence was thick—as if the bodies had absorbed all the sound, like flannel. Like blankets. Like snow.

Body parts: She showed me first the trays of body parts: stainlesssteel basins of raw things—one full of kidneys, another of livers—like offerings in a meat market. She spoke in hushed tones, as if we were in an intensive-care room or a nursery.

Then we approached the gurney that bore the cadaver she had been dissecting for many weeks. Slowly, gently, she turned back the cover—first from the thin, white feet and legs. "We'll start here," she said. "The head is so very personal." I knew she was allowing me time to prepare for the intimacy of that encounter.

She pointed to a clipboard on a nearby low wall, where the history of her cadaver was detailed. He was an old man—and an old cadaver, it seemed, having been in storage for many months. I don't remember what it said he had died of.

In some medical schools' anatomy labs, she explained, the students make dark jokes about death and horse around, probably in an effort to handle their feelings. She was grateful that the attitude here at Dartmouth was different—one of respect for this, a human presence.

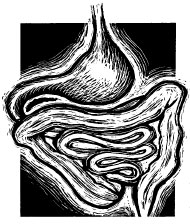

She raised the sheet from the lower torso, which was laid open like a display package. She had been working on a section of colon, I think it was. I was astonished to see that our bodies' essential parts are all neatly organized, many in their own little membranes—like plasticwrapped leftovers in a well-maintained refrigerator. I had always assumed, I guess, that the coils of the intestines, the stomach, the liver, the spleen, would be all jumbled up together—resembling more the inner workings of a radio. The tidiness of the reality before me was strangely satisfying.

Awe: By now my curiosity and, yes, my awed fascination with everything in that room had fully taken hold. "It is so important to us as students to have this experience of dissecting an actual body," she said. "And if people are willing to donate their bodies so we can do this, we must . . . must give them due respect." I felt very strong as she carefully removed the covering from the head.

I gazed down upon the small face of an old man, an old man who somehow linked my daughter and me and all human flesh together, in the semidarkness, in this timeless moment. He was nothing and yet everything to me.

Then up we went into the freshness of the evening—where green, growing leaves gleamed softly under a star-studded sky—full of a sense of the enduring connectedness of all living things, and of the child who becomes the parent and the parent the child.

Patsy Garlan is a much-published author who has written poetry, memoirs, stories, college texts, and a musical play. She is the mother of Sarah Garlan Johansen, a 1990 graduate of Dartmouth Medical School. Johansen—who also did her residency training at Dartmouth, from 1990 to 1993, and is now the medical director for emergency services at New London, N.H., Hospital—points out that the rules as to whom students were permitted to bring into the anatomy lab were much looser when she was a student at Dartmouth than they are today. This essay is copyright 2000 by Patsy Garlan; it was first published in the May 2000 issue of the Atlantic Monthly magazine.