Telling Johnny's Story

The phone woke me from a deep sleep. It was a nurse with some questions about chemotherapy for Juan "Johnny" Pardo. But Johnny was dead. Wasn't he? I rolled over and opened my eyes. The phone was still resting in its cradle. It was only a dream.

By then fully awake, I remembered Johnny, lying motionless in his coffin, dressed in his Sunday best, his bald head covered by a baseball cap. I had seen that cap so many times (more times than I had actually seen hair on his head), but his face had never been that doughy and gray. Yes, Johnny was dead.

I am a pediatric oncologist-I take care of kids with cancer and blood diseases. When people learn of my occupation, their first response is usually, "Oh, that must be so hard."

That's true, though I am usually able to keep my work from interfering with my family and home life. I can count on two fingers the number of times I've dreamt about my patients. But in death as in life, Johnny had a special grip on me.

I first met him in the intensive care unit at Children's Hospital in San Diego, where he was admitted because his white blood cell count was dangerously high. The admitting ICU nurse quickly and efficiently started an intravenous line and placed leads for the cardiac monitor on his chest. He was the most alert and healthy-looking patient that came through the ICU doors that day. After examining his blood smear under a microscope, I knew that he had acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Then only 15 years old- with a Spanish-speaking mother from Mexico, two sisters, and a father who was no longer in the picture-Johnny was the man of the family. He was shy, reticent, and scared; he spoke with his eyes.

His subsequent course was rocky at best, with many relapses of the leukemia, especially in his spinal fluid and left eye. His tedious and taxing chemotherapy schedule was interrupted on occasion by blood infections and transient episodes of weakness, tingling, and garbled speech.

One time, his whole right side went numb. "Dr. Schiff, it's Johnny. My right side feels funny, and I can't really move it very well," he told me over the phone that day. "Johnny, where are you?" "I'm calling from my cell phone. I'm in my car. I was driving when it happened, so I pulled over to the side of the road." "Johnny, hang up and call 911 right away. When they come, have them bring you to the hospital immediately."

But as quickly as it had come on, the weakness went away, so he ended up driving himself to the clinic. He was admitted for evaluation. His spinal fluid did not show any leukemia or infection, and an electroencephalogram ruled out a seizure. An MRI of his brain revealed the most likely cause of his brief weak spell-there were some whitematter changes that suggested damage from chemotherapy and radiation.

Another time his mother brought Johnny to the clinic because he wasn't able to speak. He seemed to understand what people were saying, but when he opened his mouth to talk, gibberish came out. I questioned and examined him.

"Johnny, does your head hurt?"

He shook his head no.

"Does the light bother your eyes?"

No again.

"Any fever? Vomiting?"

No and no.

"When did this start? Cuando lo empezo?"

"Nordacked evha selp," he said, pleading but incomprehensible.

His mother explained, in Spanish, that he had been in Mexico over the weekend. He'd returned early the night before because he wasn't feeling good. Then in the morning he had woken up unable to speak.

"Did you have anything to drink or use any kind of recreational drugs?" I asked next.

No.

"El no bebe o toca drogas," his mother corroborated.

I observed that the left side of Johnny's face was drooping. This was new.

"Put out your arms and pretend that you're holding a pizza. Now close your eyes."

Johnny followed my command. Slowly his right arm drifted inward and downward.

"Okay. You can open your eyes. We're going to get a CT scan of your head."

"Nordacked," Johnny answered. Then he scrunched his eyes and shook his head. I sensed that his mind was still sharp. He knew that something was wrong. He clearly had something that he wanted to tell me. But his thoughts and words were shuffled and swirled. Expressive aphasia-that was the medical term for it.

The clinic nurses knew that Johnny "wasn't himself." That much was obvious. They hovered and fretted, waiting for an explanation and a plan. After I finished examining Johnny, I updated Amy Clark-an experienced clinic nurse who had known Johnny for years. Amy had always been there for him with an encouraging word or a welltimed joke.

"I'm going to admit Johnny," I told her. "I want to get an emergency CT of his head to rule out a bleed. A stroke is also possible, but less likely."

"I'll go with him to radiology and stay with him until the scan is finished," Amy said. She was clearly frightened, too, but she put on a brave face for Johnny's sake.

The head CT was negative. Johnny was admitted and started on Decadron to keep his brain from swelling. The following morning he was much improved and was again able to speak. He had a spinal tap that morning that showed leukemia cells. This was his third relapse in his spinal fluid. I met with him to share the results of the tests.

"Johnny, I think that your symptoms were from leukemia in your spinal fluid. You're going to need chemotherapy into your spinal fluid once a week for at least a month. You'll also need stronger IV chemo, and you'll need to stay on Decadron, too."

"That's what I was trying to say yesterday," Johnny said. "I wanted Decadron. That always makes me feel better."

I was shocked both by his rapid improvement and by his remarkable cognizance of his body and his disease.

Despite a demanding chemotherapy schedule, Johnny balanced his treatment with a full life outside of the hospital. He graduated from high school, then started college as a full-time student, and had two (or was it three?) sequential "serious" girlfriends. Sometimes he rescheduled or simply missed medical appointments. Once, the nurse case manager informed me that he had delayed a chemotherapy admission to take a well-deserved vacation.

"How was your vacation?" I asked him when he returned.

"I went to Juarez on a church retreat." I had read in the San Diego paper about Juarez-a Mexican city, just across the border from El Paso, that has one of the highest crime rates in North America. Over the course of a decade, hundreds of young women-most of them underpaid factory workers-had been abducted, raped, and murdered there. In the newspaper article, a Mexican feminist was quoted as saying, "If Juarez is a city of God, it's only because the Devil is scared to go there."

"How did you get there?" I asked Johnny.

"I split the driving with another guy. We drove our church van. . . . Unfortunately, it didn't have air conditioning. . . . It took about 14 hours. It would've been faster but we got stuck in traffic for about two hours. We had to pass a four-car accident. It was like a parking lot."

"That sounds terrible," I said sympathetically.

"No, it was good. We helped fix the roof of a church and organized a baseball tournament for the kids. It was great-I met some really nice people." Johnny was passionate about his faith in God.

In my Introduction to Psychology course in college, I had learned that a strong bond is formed between two people when they look into each other's eyes. I always had a special place in my heart for Johnny, perhaps because of all the times I had looked deep into his eyes to check for leukemia there. But that's not the only reason. He was such a fine young man and an inspiration to everyone who knew him.

He was invited to attend a ski camp in Aspen, Colo., for teens with cancer. (I sent him with a prescription for Decadron, "just in case you need it.") The organizers of the trip enjoyed Johnny so much that they specifically asked for him to come back the next year. He participated in other activities for teens with cancer, too: he went on an annual fishing trip and an annual trip to Magic Mountain amusement park.

Unfortunately, some of his best friends from the hospital who went with him on these trips fought hard but could not beat their cancer.

After the second time the leukemia reappeared in Johnny's spinal fluid, I tried to talk him into undergoing placement of a reservoir to make it safer and more efficient to deliver chemotherapy into his cerebrospinal fluid. The reservoir was called an Omaya. I explained its benefits and how it worked.

"I'll think about it and talk to Roberto about it because he has one," Johnny replied.

"Oh, honey. I'm so sorry. Roberto passed away. I thought you knew."

"No, that was Julio."

"I'm really sorry. They both died. I'm sorry to be the one to tell you."

Johnny never got an Omaya.

Iheard Johnny speak ill of another person only once. While I was on vacation with my children, visiting my family in New York, another Children's Hospital oncologist, Dr. Simon Kaye, saw Johnny. According to the clinic schedule, Johnny was due to be admitted for chemotherapy. But he felt sick. He was tired and weak, and he had a lowgrade fever. He told Amy that he wasn't feeling good. She could tell by looking at him that something was wrong. She drew a blood culture from his central venous line, along with the usual blood work.

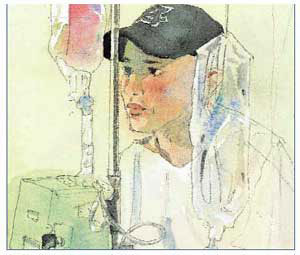

Illustration by Bert Dodson "That's what I was trying to say yesterday," Johnny said. "I wanted Decadron. That always makes me feel better." I was shocked both by his rapid improvement and by his remarkable cognizance of his body and his disease. |

When the doctor went in to examine Johnny in preparation for admission, he scanned Johnny's chart and said, "It looks like you're due for admission for ARA-C." ARA-C is strong chemotherapy that would knock down Johnny's blood counts, give him a fever, and make him feel achy all over.

"I don't really feel up to it. I was hoping that I could put it off until next week because I've been feeling sick."

"You look fine to me."

"I've had a fever."

"How high?"

"A hundred."

"That's just a low-grade fever. You probably had a virus or something. . . . What happened to your elbow?"

"I scraped it in a bicycle accident." The doctor poked at the large abrasion on Johnny's elbow. "Does this hurt?"

"What do you think? Of course that hurts."

"I don't have the results of your blood counts yet, but if they're good, I'm admitting you for chemotherapy." It turned out that Johnny's counts were not good enough for admission.

I returned to work the following day. Early that morning, I received a call from the microbiology lab. The blood culture that Amy had drawn from Johnny's catheter was growing bacteria: Gram-positive cocci in clusters. Johnny would need a repeat blood culture and admission for a course of intravenous antibiotics.

I called Johnny to tell him to come back to the clinic because of his positive blood culture. He gave me an earful. He said he was appalled that Dr. Kaye had poked at his scraped elbow and had thought Johnny was faking an illness to avoid hospitalization- or, worse, had thought Johnny was a wimp who couldn't tolerate a little discomfort.

"Dr. Kaye is a punk doctor," he pronounced. Later that day, when I visited Johnny in his room on the hematology-oncology unit, Diana Rodriguez, the heme-onc social worker, was already there chatting with him. Because she is bilingual, she works with many of the Spanish-speaking heme-onc families. At times she had been asked to translate heartbreaking news: to tell parents that their child had cancer, or that the cancer had spread, or that there was no cure. Diana has a calm and professional manner. She always wears her thick, dark hair pulled back in a loose ponytail with gentle curls. Her voice, too, is undulating and gentle. Her eyes are big and dark and her gaze nonthreatening but direct.

"Dr. Schiff," Diana said, "Johnny was telling me that he had to park three blocks away from the hospital because he didn't have the four dollars for parking. I think we can get him a parking pass if I write a letter to the hospital administrators explaining his situation."

"That would be great."

"Johnny, when were you diagnosed?" Diana asked him.

"Six years ago."

"And when did you relapse?"

"Which time? I've had seven relapses."

"Seven? Really?" She had been a hemeonc social worker for 15 years and had never heard of anyone with ALL relapsing seven times. Most ALL patients either were cured or had died after the second, third, or, at most, fourth relapse. She turned to me to get the truth.

"Is that right, Dr. Schiff? Seven relapses?"

"Yep, that's right."

Before going home from work that day, I checked my e-mail. In my in-box was a copy of a message from Diana to Dr. Arnold Kaplan, the medical director of the hospital:

Dear Dr. Kaplan, I am writing to you concerning Juan "Johnny" Pardo, a 21-year-old with ALL who was diagnosed at age 15. He has had seven relapses and has remained on chemotherapy since he was diagnosed six years ago.

Johnny recently had to park three blocks away from the hospital because he didn't have enough money to pay for parking. Johnny receives $450 per month in the form of state disability. He pays his mother $150 per month for rent. He pays another $150 per month for car insurance. That leaves only $150 per month for all his living expenses. He is a full-time college student who hopes one day to become a general pediatrician. He wants to be able to help children stay healthy.

It would be of great assistance if Johnny were able to obtain a permanent parking pass. He is seen in the hematology clinic on a weekly basis. Sometimes he has to be admitted to the hospital for up to one week at a time. The $4.00-a-day parking fee adds up very quickly. Thank you in advance for your assistance in this matter.

Sincerely,

Diana Rodriguez

Hematology-Oncology Social Worker

Johnny got approval for a permanent parking pass the next day.

Miraculously, Johnny recovered from his infections and neurological spells. His blood cultures cleared up and his brain MRI even improved somewhat. However, his left eye continued to be his Achilles heel, and his refusal to have surgery to remove that eye haunted me. In my heart I felt that enucleation-removal of the eye-followed by bone marrow transplantation was his only chance for a cure. I felt like a broken record as I told him this again and again.

"You don't want that eye. You can't see with it. It just causes problems. Why don't we arrange to have it removed? Lots of people have false eyes. If you're worried about how it'll look, we can arrange for a plastic surgeon to be involved. It won't even be noticeable."

"I'll think about it."

"Johnny, I know you," I responded. "'I'll think about it' means that you don't want to do it and that you don't want to talk about it. You've been 'thinking about it' for three years now. Your leukemia has come back seven times. There are still leukemia cells in your eye. If we don't get rid of the leukemia there, it will keep coming back. And if it comes back in your bone marrow, I don't know what I'll do. I don't know of any chemotherapy that can work in that setting- and I will be very sad."

Tears pooled in my eyes as I spoke but did not fall. I had a point to make. "Your best chance of cure is a bone marrow transplant. Your sister is a perfect match. But I don't think it would be right to make you suffer through a bone marrow transplant if you still have leukemia in your eye. The leukemia will just come back. And it wouldn't be fair to your sister, either."

"I know. I understand what you're saying. I listen to what you say, and I'm thankful for what you have done. But I have to listen to God. It's in God's hands."

"Johnny, you can't see with your left eye. You've already had seven relapses. Maybe that's God's way of telling you that you need to get rid of that eye."

"I have faith. It's a miracle that I'm still alive. I've relapsed seven times but I'm still here. . . . I think that I must be here for a reason. . . . I want people to see that miracles can happen."

I paused for a moment, trying to think of a better approach, a way to win this argument. Let me talk in words that he can relate to. "Isn't there a part of the Bible that says, 'If your eye offends you, pluck it out'?" This was the first time I had ever quoted the Bible to anyone. In fact, one of the more pious anesthesiologists had provided me with that quotation.

"That's not what that means," Johnny responded. "That part of the Bible means that if your eye causes you to sin, then you should get rid of it." He smiled, knowing that I was out of my realm.

"Well, just think some more about what I've said. Okay?" I knew the conversation was over and that once again Johnny would not be swayed by facts, reason, or even the prospect of his own death. Daunted by his faith, I realized that Johnny lived each day of his life the way he wanted to live it. He had no regrets and he had no fear of death. I had done my best as his physician, and he knew how much I cared about him.

"Thank you. God bless you," he said.

I felt blessed.

Johnny's 10th relapse was the fateful one. At 22 years of age, he had a relapse in his spinal fluid and bone marrow. I myself calculated the number of blasts in his bone marrow: 45 percent. I knew what this meant-he would need a miracle to be cured of his leukemia. I knew that he, too, would be aware of the implications of this awful information. He took the news well.

"It's in God's hands," he said. He didn't cry.

He received more chemotherapy, which lowered his blood counts and drained him of energy. Yet he still went fishing with his uncle almost every day. And he kept his clinic appointments as scheduled.

"Your infection-fighting cells are very low," I warned him. "You need to call immediately if you have a fever."

"Have a little faith," Johnny admonished me.

"I have faith in you," I told him.

"Dr. Schiff," he replied simply, "I know you believe."

The fever did come, and with it chills and lightheadedness. Johnny drove himself to the emergency room. His blood pressure was very low. He was resuscitated with IV fluids, but that wasn't enough. He was transferred to the ICU, where they started drips to raise his blood pressure. Before morning, he was intubated and placed on a respirator.

I visited him in the ICU. His body was motionless except for the rise and fall of his chest as the ventilator forced air into his lungs in a steady, harsh rhythm. This is it. There won't be any more miracles.

Johnny's care was no longer within my domain. The ICU team took over. They managed the ventilator settings and the blood pressure drips. When an abnormal heart rhythm showed up on his monitor, they started another drip to alleviate it. They were far more aggressive than I would have been, and I was somewhat relieved that I wasn't making the life-or-death decisions at this point.

I continued to visit Johnny, mostly to support his mother. Diana often helped to translate. It was hard for me to see Johnny in that state, unable to move or speak. That's not Johnny. His soul has already left his body. After one of my visits, Diana commented to me, "Did you notice that Johnny's heart rate slowed whenever you spoke? You had a calming influence on him."

"Noooo," I responded in disbelief.

"It's true," she said.

After a week of high ventilator settings and even higher pressor drips (using Levophed- a drug so powerful that it's referred to as "leave 'em dead"), Johnny turned the corner. His lungs improved, his blood counts rose, and his blood pressure stabilized. The ICU team weaned him from the pressors and pulled out the breathing tube. The next few days for Johnny were like a dream. A steady stream of visitors poured into his room, all with good wishes, encouraging smiles, and congratulations on his remarkable comeback.

Even the jaded ICU staff allowed themselves to celebrate his recovery as a grand victory. One seasoned nurse, who remembered Johnny from his diagnosis seven years earlier, told me that he amazed her-she said that she had never seen anyone survive after being on such high doses of Levophed.

Illustration by Bert Dodson After a week of high ventilator settings and even higher pressor drips, Johnny turned the corner. His lungs improved, his blood counts rose, and his blood pressure stabilized. The ICU team pulled out the breathing tube. |

Within a few days, Johnny was too stable for the ICU. He was transferred to the hemeonc unit, where his rehabilitation started. He was so weak he had to relearn the basics like how to eat and walk. But Johnny was riding a natural high and was prepared for the hard work of physical therapy-PT, referred to by some patients as "pain and torture."

His first day back on the heme-onc unit, I watched him sip some soup his mother had brought from home. Then I got my first good look at his left eye. It was swollen, gray, and bloody. It's a ball of leukemia!

"It's great to see you up and around. You were very, very sick. You'll have to eat more and get stronger before you'll be ready to go home."

"I know. I'm eating soup, and I took a short walk yesterday."

We kept it simple-just eating and walking. Neither of us mentioned the elephant in the room.

Outside in the hallway, Diana read the look on my face. "What's wrong?" she asked. "Did you see that eye? My God!" "He's in for a big letdown," she agreed. "He's so high right now and his faith is so strong . . ."

A few days later, Diana and I met with Johnny and his mother. It was time to have a talk. We had heard through the grapevine that they did not want any more chemotherapy. Johnny's mother was certain that it was the chemotherapy that had almost killed him. Relapsed leukemia is a bad disease. Without treatment, it is a fatal disease.

"We don't want any chemo now. When he is stronger, we would like for him to have the bone marrow transplant," his mother explained.

This was magical thinking, I knew. First, he would need very strong chemotherapy to rid that eye of leukemia. Second, bone marrow transplantation includes giving the patient ultra-high doses of chemotherapy and sometimes radiation therapy to wipe out the diseased bone marrow cells; you cannot undergo a bone marrow transplant without having chemo. I explained this (again). We discussed other options-milder chemotherapy by mouth at home, or no more chemotherapy and comfort measures only. We agreed to let Johnny and his mother "think about it" some more.

They were forced to make a decision a few days later when the lab reported blasts in his peripheral blood and a white cell count that was doubling every day. They chose the daily oral chemotherapy. They also agreed to intrathecal chemotherapy-delivering chemo directly into his spinal fluid.

My last talk with Johnny occurred after the spinal tap. He was happy and at ease. Words flowed from him. They must have been bottled up inside him during those weeks in the ICU. We chatted like dear friends. I felt I could ask him anything, as if we were playing that old game "Truth or Dare."

"Johnny, you know that you have blasts in your blood. Is there anything you want to accomplish while you're still able-any family or friends whom you would like to see? Can we help you set something up?" I knew that Johnny was too old to qualify for the Make- A-Wish program, which grants special requests to children with life-threatening illnesses, but perhaps we could come up with something.

"My mom and I and some friends are planning a trip to Cancun next month," he said.

Now that would be a miracle if he makes it to next month. Even if he is still alive, he'll be as sick as a dog. "I don't know if you'll be well enough to make that trip. Maybe we can find you a beach house here in San Diego." I knew of some wealthy families who might be willing to loan out their beach house for such a worthy cause. "I'll see what I can do about setting that up. Then if you're well enough a month from now, you can still go to Cancún. . . . Johnny, do you remember anything about your time in the ICU?"

"I had some weird dreams," he said. "I dreamt that I was on a yacht and it was being pulled by an ambulance. I think my mother was driving the ambulance."

"I wonder what that dream means. Maybe the yacht was taking you to heaven but the ambulance pulled you away from there. Did you hear God's voice?" I asked him.

"I may have but I don't remember."

"Did you see a bright light?" I felt compelled to ask about all the cliches, and he proved willing to humor me.

"No."

"Did you talk to anyone who's already dead?"

"Well, my sister told me that my grandmother died. So when my grandmother came to see me, I set off all the alarms on the monitors."

"Your dead grandmother came to see you in the ICU?"

"No, my sister told me that my grandmother died, but she really didn't. She's alive.

My sister was just testing me to see if I understood what she was saying. So when my grandmother came to visit me a few days later, the alarms went wild."

"Do you remember that?"

"Not really. My sister told my mother what she'd done, and, boy, was my mom mad at her!"

We laughed.

Afew days later, Johnny developed a serious blood infection, even worse than the one before. He took the familiar trip to the ICU, was put on a respirator and blood pressure drips, and died a few hours later.

Just before the end, Diana and I met with his mother. "Johnny is not going to make it," I told her. "We don't have any medicines that will cure his leukemia, and his organs are severely damaged."

She stared ahead with a glazed look- making no eye contact with either of us- but did not cry. I need to be sure that she gets it. I need to see tears.

"If there's someone you need to call before he dies, I think you should do it now."

"Okay."

Without shedding a single tear or saying another word, she got up to make her phone calls. She called her pastor and friends from her church. It was this church, this faith, that was allowing her to face this unthinkable grief without a tear.

I'm not sure if I believe in Johnny's God, but I believe in Johnny and his miracles. That's why I honor his life and his faith by telling his story. That's all I can do now.

If you would like to offer any feedback about this article, we would welcome getting your comments at DartMed@Dartmouth.edu.