In Schweitzer's Shadow

Three months of working at the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Africa. Three months of contemplating the legacy of the fabled French humanist. Three months of pondering his own future in medicine: A Dartmouth medical student reflects on his time in the shadow of the late great medical missionary.

By William Anninger (email)

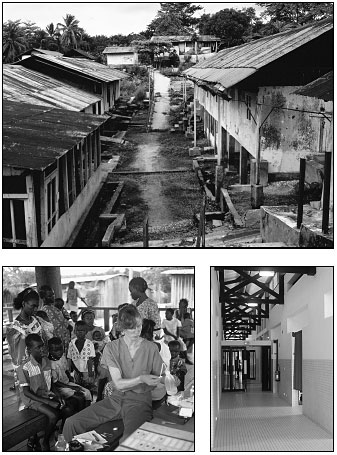

The author is pictured here tending a patient's leprous foot. The complex where he worked includes a separate lepers' village that Schweitzer established with his Nobel Prize proceeds.

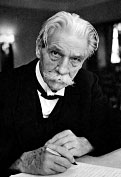

Albert Schweitzer: The name is certainly well-known. But who was this pensive, tired-looking man, always pictured wearing colonialist khaki and a safari helmet? And why was he so revered?

As I applied to spend three months at the famed Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Lambarene, Gabon, I couldn't help pondering these questions. At times I found myself cynically questioning whether le grand docteur was as great a man as his Nobel Prize suggests. Perhaps, I wondered, he was honored not for what he did but for what he gave up: European prestige, fame, and scholarship. Would a young man who had established a hospital in central Africa but was simply a doctor—not also a world-renowned theologian, philosopher, and organist—have been similarly honored? Or would an African who had followed a similar path have been so lionized?

But on my less cynical days, I imagined that Schweitzer's deeds were legendary because people understood his wisdom in applying his skills and good fortune where they were most needed.

Despite my intermittent skepticism, I felt a connection to Schweitzer's philosophies and mission. I understood his desire to "be able to work without having to talk," to immerse himself in his work. I even shared his frustration at being an older medical student. He wrote in 1933: "All my interest in the subject matter could not help me overcome the fact that the memory of a man over 30 no longer has the capacity of a 20-year-old student's."

Le debut

Now here I was, a 33-year-old medical student, waiting apprehensively at Boston's Logan Airport. In one hour I would board a plane and head off for three long months to the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Gabon. I asked myself why I was going to Africa—actually, going back to Africa, for I had spent two years in the Republic of Niger after college, working as an agroforester. Was I going back for the work, for the cultural experience, or to discover something new? Or was my motivation just to postpone a while longer the difficult decision of what medical specialty to enter after graduation? Throughout the series of long flights to Gabon I had ample time to contemplate my now irreversible decision to escape for a few months to Africa.

When I stepped off the plane in Libreville, the capital of Gabon, the sticky night air enveloped me. It all felt familiar: the heat, the rhythm, the laughter, the relaxed way everyone moved, the dimly lit streets, the eyes peering out of shadows, the inviting and putrid smells swirling everywhere. The functional disorder of this capital city was hypnotizing. The stresses of the developed world faded away, only to be replaced by more fundamental concerns: What am I going to eat and drink? Am I going to survive this car ride?

A few hours later, I was sitting on a well-worn wooden bench in downtown Libreville. A plastic plate piled with sizzling carp and fried bananas in a scorching red pepper paste was placed before me; then a large bottle of Orangina appeared. Diesel fumes mingled with the spicy piment (red pepper). I was starting to feel at home; maybe things were going to be okay after all. I began to look forward to the trip the next day to Lambarene, home of the Schweitzer Hospital.

Qui etait Albert Schweitzer?

So who was Albert Schweitzer? He was born on January 14, 1875, in a rural village in Alsace—then a part of Germany, though previously and now once again a part of France. His father was a Lutheran pastor. Young Albert was gifted musically and, after showing particular talent on the organ, studied with several of Europe's preeminent organists. In 1893, he entered the University of Strasbourg and, following stints at the Sorbonne and the University of Berlin, received a doctorate in philosophy in 1899. Already, he felt a strong desire to teach and share his thoughts with others.

He started his professional life with an appointment on the pastoral staff of St. Nicholai's Church in Strasbourg. By 1900 he had completed an advanced degree in theology and by 1902 was a professor of theology and philosophy at the University of Strasbourg, principal of St. Thomas College in Strasbourg, and curate of St. Nicholai's. At the same time, he became the world's leading expert on organ-building and published several books on theology and music.

Although his achievements were already great, Schweitzer wanted his life's work to involve direct service to humanity. He agonized about his place in the elite world of European academia.

|

Although his achievements in academia were already great, Schweitzer wanted his life's work to involve direct service to humanity. |

Then, in 1904, he read in a missionary journal that doctors were desperately needed in the French Congo—now the independent country of Gabon, but then a French colony. The article struck a deep chord, and within two years he was a 30-year-old medical student. This dismayed his family, friends, and colleagues, who felt he was making a great mistake in leaving behind his well-established career. Nonetheless he persevered and finished his training at age 38, having specialized in infectious diseases and surgery.

Schweitzer and his wife, Helene, raised funds for their intended missionary work, bought a supply of medical goods, and left for Africa in March of 1913. They planned ultimately to build a hospital in Lambarene but started treating patients right away in a small chicken coop that still stands today.

|

|

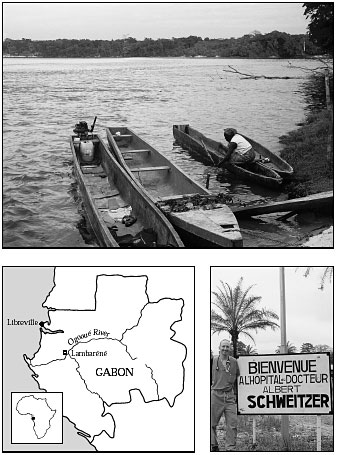

The Ogooue River (top) and the surrounding rainforest are the dominating features of Lambarene, Gabon, home of the Schweitzer Hospital. At right, the author is pictured at the entrance to the hospital's grounds. |

Voici Lambarene

The road between Libreville and Lambarene was hemmed in on both sides by rainforest—a dense, aggressively green tangle. The jungle looked totally impenetrable and even slightly menacing.

By the time I arrived at the hospital, I was tired and disoriented. With my American eyes, I found it hard not to be dismissive of the haphazard layout of the hospital grounds, the run-down buildings, and the rutted roads.

The Ogooue River, however, made an instant impression on me. The wide, powerful river, which borders the eastern side of the hospital grounds, teems with life. Above its banks, trees drape their heavy limbs down to the water's surface. And what at first glance appears to be simply a leafy tree often turns out to be a canopy full of monkeys, plucking fruit from the branches. Down below, the ripples part as a massive hippo surfaces, expels a steamy breath, and then slips mysteriously back into its wet, muddy world. Inhabiting the river's depths are an abundance of ilomba, a mid-sized carp that is a staple of the local diet. And skimming across the water's surface are fishermen and merchants traveling in carved-out logs with 15-horsepower outboards clamped to the back: an ancient design with a modern wrinkle.

During Schweitzer's time, I learned, the river had served as the region's major thoroughfare, and most hospital supplies and patients had arrived by boat. The original, now-vacant hospital buildings, mostly defunct and in disrepair, lie along the riverbank. Today, the main hospital buildings are far from the Ogooue, and the river's central role has been supplanted by the ribbon of pavement running between Libreville and Lambarene.

I also soon became entranced by the rainforest. Excursions into its depths could be frightening. I saw huge snakes baking on dirt paths and elephant footprints the size of dinner plates. Locals described dangerous encounters with gorillas, wild boars, and crocodiles. But the jungle also cast a mystical aura, with trees and plants constantly in all stages of growth, death, and awakening—some blossoming with spring-like lushness, others dropping dry leaves or shedding chestnut-like seeds.

As in most rainforest regions, the topsoil is thin and fragile. Deforested areas can become quickly denuded, leaving a dense, rocky, red clay surface. Gabonese farmers, primarily women, practice slashand- burn agriculture. The cycle begins in the dry season, when a piece of jungle is chosen and all living trees, plants, and vines are felled. Then, rather than clearing the plot, the women light a fire that burns out the dry leaves and undergrowth. What remains is a jumble of charred, criss-crossed trunks, through which the edible plants are grown. Because of the weakness of the soil, farmers are only able to grow their bananas, manioc, and sweet potatoes at a given site for one year, after which the land must lie fallow for many years before it can be used again. Fortunately, there is still much unused land, though I wondered how long this would be the case.

I found myself troubled as well by the sight of huge logging trucks struggling out of the jungle, loaded with gigantic tree trunks bound for timberhungry nations.

Le respect de la vie

It was soon after he arrived in Africa that Schweitzer developed his now-famous ethical philosophy, "reverence for life." In a 1964 essay, he wrote about his feelings during those early years: "I continuously pondered the question: does our civilization truly possess the ethical character and energy essential to its complete fulfillment? This led me further and further into studies of civilization and ethics as they appeared in philosophical writings. . . . The most important philosophical writings of the time, I discovered, looked upon civilization and ethics as things we had received, things left to us, to be taken for granted and accepted as such. I could not escape the impression that an ethical system regarded as final did not demand much of people or society. It was, in fact, an ethic 'at rest.'"

Schweitzer felt that core moral and human ethics were values that needed to be worked at and practiced daily, that they were not inherent in society. He also felt that any ethical code focused only on how humans interact with humans was fatally flawed. He was convinced that a true ethical code had to include animals and the earth—all coexisting members of the global system.

While floating up the Ogooue one day in 1915, he was struck with the phrase "reverence for life," which he used as a guiding moral philosophy from then on. He described this revelation: "'Reverence for life' struck me like a flash. . . . I realized at once that it carried within itself the solution to the problem that had been torturing me. Now I knew that a system of values which concerns itself only with our relationship to other people is incomplete and therefore lacking in power for good. Only by means of reverence for life can we establish a spiritual and humane relationship with both people and all living creatures within our reach. . . . Through reverence for life, we come into a spiritual relationship with the universe. . . . The fundamental fact of human awareness is this: 'I am life that wants to live in the midst of other life that wants to live.'"

Ironically, soon after he developed this centering moral philosophy, Schweitzer and his wife were forced to leave Gabon as prisoners of war. World War I had been raging for months, and German citizens were not safe in a French colony. The Schweitzers were held in a series of POW camps until the war's end, when they returned to Alsace. In 1919, they had a daughter, Rhena, and in 1927, Schweitzer returned to Lambarene—this time without Helene, whose health was failing. As the years passed, his hospital and his fame grew. Every few years he traveled back to Europe to visit friends and family and to raise money at speaking engagements or organ recitals. Increasingly, too, Westerners visited Lambarene to see le grand docteur in action. In 1953, his commitment to humanitarian work was honored with the Nobel Peace Prize.

In his later years, Schweitzer became deeply disturbed by the development of nuclear arms and their use in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In 1957 and 1958, he made worldwide appeals against the proliferation of nuclear arms and published several antinuclear texts. He died in 1965 at the age of 90 and is buried on the hospital grounds by the banks of the Ogooue.

|

Schweitzer felt that core moral and human ethics were values that needed to be worked at and practiced daily, that they were not inherent in society. |

La medecine

As for myself, I went to Gabon hoping primarily to learn a lot of medicine. I was still agonizing about what specialty to go into, so I decided to work on the internal medicine service, where I would be exposed to the broadest variety of cases. I had just completed my third year of medical school but did not yet feel very confident about my skills or my ability to be a "good" doctor. I hoped to gain more experience and to develop inner strength about my clinical abilities during my time there.

My first month was difficult. Four weeks before my arrival, a six-year veteran of the hospital's internal medicine staff had quit to start a new life elsewhere. And the only other experienced physician on the service left for a two-month vacation just a few days after my arrival. Without these two M.D.'s, there was no one to give me any direction. Then two German physicians arrived as replacements. At first, my new colleagues were as overwhelmed as I was. In addition, they seemed to clash and were not supportive of each other. Their inef- ficiency and lack of confidence soured the mood on the whole inpatient ward, and even the nurses seemed frustrated. In such a setting, I found it dif- ficult to feel invested in my work. I even questioned the quality of care patients were getting; it appeared to be dismayingly random. But with time, as is often the case, the relationships, the mood on the service, and the quality of care improved.

I spent the majority of each day at the poly-clinique (outpatient clinic). There, I met the friendly and warm people of Gabon, had daily encounters with young and old, heard multiple dialects, and saw a great variety of pathology. The patient encounters pushed me to focus in a way I never had before; I would catch myself actually leaning forward to better absorb a patient's story. (French is the common language in Gabon, due to its history as a French colony. Most Gabonese speak some French, in addition to one or more tribal languages. Fortunately, my own French is fluent, for I was born in France, and I found it sufficient for most patient encounters.)

For the most part, I felt I provided good care— certainly the best I was capable of—but every day there were cases I did not understand. Feelings of unease and incompetence could overwhelm me as patients left my office with problems I was afraid I had misunderstood. Why was I being given so much responsibility? I had never before been asked to care for patients all by myself. Yet after several weeks, I came to believe that in Gabon, where trained caregivers were few and far between, I was actually relatively well qualified to be seeing patients.

Within the first few days, I could tell that my patients were capturing me emotionally. I would often awaken with a start, realizing that a patient had failed to return for a follow-up visit. There was the man with seizures who disappeared after I started him on phenytoin, an antiepileptic. The grandfather with polydipsia and polyuria—excessive thirst and urination—who never returned to find out that his blood sugar was off the chart. The sickly woman whose positive HIV test results sat in my bag for two months. The coughing, emaciated 30-year-old whose chest x-ray revealed the ravages of tuberculosis. I had carefully explained to him that his condition presented a significant risk to his family and his entire community. Damn, had he not sworn he was coming right back to be admitted!

|

|

The main hospital buildings from Schweitzer's time (top) now stand abandoned and in disrepair. Today, care is dispensed everywhere from open-air clinics in remote areas (above left) to the internal medicine ward—the hospital's newest and most modern—at the Lambarene facility (above right). |

La realite

There were also many patients who, despite a thorough work-up and careful deliberation, I had to send away without a solution. I remember the bewildered elderly man who complained of difficulty swallowing; when he opened his mouth, I could see an ulcerated neoplasm the size of a golf ball. I can still see the face of the 30-year-old logger who was stunned by the news that he was HIV positive; I had suggested the test after he complained of fatigue, diarrhea, and a 10-kilogram weight loss. "What will my wife and four children do?" he wondered. Then there was the 18-year-old with painful and severely disfiguring lymphedema in his legs. His shoes and pants had been customized to fit over his grossly disfigured feet and lower legs. Was the swelling filarial elephantiasis—caused by parasitic worms obstructing the lymphatic system? Or was it podoconiosis—caused by walking barefoot on soils rich in silica particles, which get lodged in the lymphatic vessels? Or was it some other illness I was failing to detect? After several days of blood tests and an ultrasound, all that the other internists and I could offer him were elastic stockings and advice to keep his legs elevated.

I grappled constantly with the reality that in the developed world many of these problems had good medical or surgical solutions. How unfair that these Gabonese should die young or live in permanent pain and disfigurement when treatment might be only a plane flight away. HIV infection offered the most dramatic example of this disparity. No therapy was available at the Schweitzer Hospital, while elsewhere revolutionary, life-prolonging drugs were achieving dramatic results.

AIDS was the most emotionally taxing part of my work. I had often considered a career working with cancer or AIDS patients, feeling that my personality might be well suited to the intimacy involved in caring for those with chronic illnesses. However, I began to have second thoughts whenever I had to break the news that patients were HIV-positive. They often took the news stoically, though they made comments like "So, I will die soon," or "How could I have gotten it? I don't fool around at all these days." I found myself falling into a reassuring monologue to explain AIDS and its repercussions: "Papa, ce n'est pas recemment que vous avez eu cette infection . . ." (Father [a respectful greeting in Gabon], it was not recently that you got this infection; it could have been five or ten years ago that you were exposed to the virus. You must be very careful of infections now; if you have a fever, you must immediately go see a doctor . . .)

I began to wonder how many of the patients I was treating for all of life's other illnesses were HIVpositive. I requested an HIV test only when there was clinical suspicion, and about 70 percent of the tests came back positive. Over half the patients admitted to the hospital with tuberculosis were HIVpositive. In addition, sexually transmitted diseases appeared (in the absence of good diagnostic tests) to be rampant. Many young women presented with pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancies, or infertility.

I soon learned that my cultural response to AIDS was different from that of many Gabonese. I was once reprimanded by a lab technician for doing HIV tests at all. And one African doctor refused to tell a patient his positive result, choosing to inform only his wife. "The patient will need all his strength to fight the illness, and knowing this diagnosis will devastate him," he explained to the stunned woman. At that moment I held my judgment, since I had great respect for the doctor. Later, I wondered who was going to be there for her if she tested positive, and how her husband would know he must practice safe sex. Traditionally, the extended family is the welfare system in Africa; the sick and needy are cared for by a family member with more resources. But the social stigma surrounding AIDS often left HIV-positive patients and their spouses isolated and overwhelmed.

As the weeks passed, I grew accustomed to the difficult realities that made up my day. Encounters that had grieved me during my first weeks were no longer so disturbing. My confidence in diagnoses and treatments grew. My interactions with the German physicians became functional and amiable.

I had come expecting to learn a lot of medicine —the appropriate work-up for symptom X, the correct drugs for diagnosis Y. And I did, but I quickly realized that these diagnoses and treatments were different from those available almost anywhere in America. I lacked access to advanced diagnostic tests, a whole array of first-line drugs, and the sort of supervision I would have had in any American hospital. I thus was not learning "Western" standards of care.

However, the situation allowed me to learn and grow in different ways. I had never before encountered the advanced stages in which illnesses could present. The many daily histories and physical exams I conducted made my hands and ears more sensitive. I began to appreciate as I never had before the subtle sound of a cardiac murmur or the crackles of early heart failure. My hands became accustomed to palpating enlarged spleens and swollen lymph nodes. I learned about being in charge of my own patients, about puzzling out their problems late at night, and about not just double-checking but triple-checking their medication doses. I learned what it feels like when a sick person is sitting in front of you, and you and you alone will decide on the course of treatment. I learned the sensation of running late, of having 16 patients still waiting to see me when it was already mid-afternoon. I learned about being welcomed, accepted, and trusted with patients' intimate stories and worries. And, as when I was in Niger, I learned about being a foreigner, a stranger, a minority.

I will forget some of the ways I did things at the Schweitzer Hospital, such as making empiric diagnoses and prescribing specific drugs. What I will not forget are the fears and rewards that come with being trusted by patients and providing them care.

|

I couldn't help wondering whether the idealism that I envision as having been present in the day of le grand docteur was still being practiced in Lambarene. |

Philosophie

Toward the end of my stay, I couldn't help wondering whether the philosophy of "reverence for life" was still being practiced in Lambarene. The hospital offers sound treatment for hundreds of patients every week, and its laboratory publishes an impressive amount of tropical clinical research. And of course I had only 13 weeks in which to assess a complex situation and form an impression.

Yet I felt that the Schweitzer Hospital lacks the idealism that I envision as having been present in the day of le grand docteur. Just below the surface of the cordial and friendly interactions among the staff and administration were layers of tension and misunderstanding. Reminders of Albert Schweitzer's legacy were present everywhere in the physical layout of the hospital, yet there seemed to be few surviving traditions that brought to life or put into action his philosophies. The traditions that did exist —such as the concept of a "village-hospital," where the employees live on the hospital grounds— now seemed dated and dysfunctional. Hundreds of people have lived their entire lives at the hospital and thus rightfully consider it their home village. Yet they also feel entitled to free housing, electricity, and water, which tax the already financially strapped institution. Had this dissonance developed since Schweitzer's death? Or had it been this way in his time, too?

When I raised these questions with administrators, doctors, or local Gabonese, they agreed with me about the tension but felt unable or unempowered to bring about change. What seemed clear was that an incredible facility, with good technical and human resources, was not functioning optimally.

Yet despite my sense that all was not well at the hospital, my personal world in Lambarene was stable, structured, and full of daily pleasures. I was engrossed in the work and enjoyed my European and Gabonese colleagues. In the late afternoon, as I'd approach my small apartment, the neighbors' cries of "Bon soir, Willy!" would melt away any pangs of homesickness. I fondly recall evenings in neighbors' homes, eight-yearolds nimbly dribbling a battered soccer ball around my clumsy legs, the dense jungle, the ferocious rains, and the sun's sledgehammerlike intensity. I will also hold tightly to the many wondrous experiences I had as a student doctor. I am thankful for my time in Gabon because it allowed me to apply my skills in a setting where service to others and "reverence for life" made up my day.

Today, the name and image of Albert Schweitzer elicit mixed feelings. He is still revered by people of older generations, especially Europeans—those who grew up hearing about the great doctor and his sacrifices in Africa. Many young people, however, consider him just another colonialist troublemaker imposing Western ways on Africa.

My own sense is that he was an enlightened thinker, and that if he lived by his written philosophies he treated all people—indeed, all living creatures—well.

L'Epilogue

Since my time in Gabon, I've settled on a specialty choice. I hope to go into ophthalmology. I love the eye, I find it very beautiful, and treatments for diseases of the eye are quite successful. In addition, there is important and interesting public health work in the field that can be done throughout the United States and around the world.

The author, now a fourth-year student at DMS, was a 1999 Lambarene Schweitzer Fellow. The program is funded by the Albert Schweitzer Fellowship of Boston, which also underwrites public service internships based in New Hampshire or Vermont for students at Dartmouth Medical School and Vermont Law School. The photographs of Schweitzer are courtesy of the Fellowship.