Doing Battle

The Veterans Affairs medical system has long been doing battle against the special health problems of veterans. And of late, the VA has been engaged in fiscal battle. Starting on the facing page is a short story about a disabled veteran that offers insights into the patient population the VA system serves. And on the next page is an exploration of what distinguishes the DHMC-affiliated White River Junction VA and of how Dartmouth benefits from its continued vitality.

|

Kunai Grass

A psychiatric nurse at DHMC tells the tale of a WWII veteran—an archetype of the VA patient population. Although the story is fictional, the medical complications of war that it represents are all too real.

By Sybil Smith

Paul dreams he is in the kunai grass again. He's looking for his lost leg. He's not a young marine, he's an old man, but he remembers the kunai grass as if he'd never left the South Pacific. He remembers how he hated it—dense and tall and sharp, grabbing at his boots and gun—and how he loved it for the thick arms that opened up and closed behind him.

In the dream, he can't remember where he lost his leg, but he's determined to find it. His eyes are stinging from sweat. The sun is God's flamethrower. A large bird calls out in alarm. He readies his gun and wonders if the kunai grass is the last thing his eyes will rest on—this primitive, fibrous plant whose green seems malevolent, though far better than red.

He wakes, and his stump is burning. He wants some of his pain pills, but he sees that the boy is there beside his bed, his feet hanging over the end of the cot. He's not a boy, really, he's 19, the same age Paul was when he hit Guadalcanal. But kids are soft now, literally. His grandson is fat and useless, as far as Paul can tell. But his son, David, came up with this plan to have Jeremy stay with him. Paul's wife, Dot, is getting too old to take care of him alone. He's developed an ulcer on the stump of his right leg and can't wear his prosthesis any more. The ulcer has now become infected and refuses to heal. The doctors at the VA have told him he has to stop drinking and cut down on the pills. His family is all in a lather about it. Paul is 77. He feels that youth and good resolutions are so far behind him as to be irrelevant.

|

Paul readies his gun and wonders if the kunai grass is the last thing his eyes will rest on—this primitive, fibrous plant whose green seems malevolent. |

"So sue me," Paul says and laughs out loud. Jeremy stirs but doesn't wake. He's a heavy sleeper. All his life he's had the luxury of safe sleep. Paul pokes him roughly. Jeremy grumbles and snorts and comes awake. "Pops?" he says, quietly.

"I need a pill, kid." He always calls him "kid."

The boy looks at his watch, and the green wands flash in the darkness.

"It's not time," he says.

Paul can still move fast. He sits up and swings his one good leg over the bed before Jeremy can even twitch a toe. He grabs Jeremy's arm with one hand and makes a fist with the other. "Get me a flippin' pill," he hisses.

"Jesus, Pops," Jeremy says, in an aggrieved voice. "You know I'm s'posed to make you wait."

Paul lets go of him and grabs a crutch. He whacks Jeremy a good one and the kid rolls off the cot and thumps onto the floor. Jeremy stands up slowly, and Paul can see his gut silhouetted in the streetlight as he walks off to the kitchen to get the pill bottle.

When he comes back he turns the light on and moves tentatively over to where his grandfather sits. His face is all stark and trembly; he looks like a child about to cry. Paul feels a moment of remorse. He takes the bottle and shakes out two pills. He won't push it by taking three. It wouldn't do to wreck this little arrangement and get slammed in the psych ward at the VA. He gives the container back and swallows the pills with stale water. "This water tastes like it came straight out of the friggin' Connecticut," he says.

"I'll get you some fresh," Jeremy replies. His head is bowed, and his voice doesn't seem angry, just tired and resigned. Paul wants to make him mad. He's worried about the boy. Where is his core, goddammit? Where is that hot, hungry center, greedy for life?

|

|

Paul lies back down. "Don't bother," he says. "I've drank worse." There is a pause, and a bloated corpse floats into Paul's peripheral vision. He remembers being bent at a jungle pool, sucking up water after hours of tormenting thirst. He then heard a long, rising squeak and looked up to see a swollen Jap rising up through the algae, releasing a pocket of gas.

"Screw you," he says to the memory. Paul hopes Jeremy will notice this remark and follow it like spoor into a darker, more dangerous place. Paul will tell him about it, if he asks.

True, Paul has never talked much about the war. He hasn't wanted to. But now that his health is going, there might come a time when he doesn't talk about it simply because he can't. What is in his head might disappear as if it had never been. Besides, Clara, the visiting nurse, has been picking at his brain as if his skull is nothing more than a large scab. She comes every day, and at this rate she'll hit the secrets soon.

Jeremy doesn't ask, but neither does he lie down. He sits in one of the two overstuffed chairs parked against the wall. "Will it keep you up if I read?" he asks.

"Hell no," Paul says. "But I will take that water." If the kid is going to read, then Paul needs a slug of whiskey.

He reaches under his bed as soon as Jeremy leaves the room, groping for his bottle and then pulling in a couple of big swallows. He swishes the whiskey around his mouth, remembering the taste that used to bedevil him. It came after he drank the tainted water. He was convinced his tongue was rotting. He scrubbed his teeth till his gums bled. He gargled with kerosene. He couldn't swallow his food for the smell. It was not till he lost his leg that the taste departed, as suddenly as it had come. It had seemed a fair exchange at the time.

He lies back and pretends to be asleep when the kid comes back with the water. He hears Jeremy sit in the chair and open his book. Paul has seen what he is reading. It is an old paperback called Combat, Pacific Theater, World War II. It's not one of those politically correct, scholarly works that irritates Paul. Rather it's a collection of unabashedly pro-American memoirs by war correspondents and soldiers, people who were there. It is one of the books Paul keeps in the bookcase by his bed.

It was Clara who'd noticed it and plucked it out. "This looks good," she remarked. "I love reading about war. I think I must have been a soldier in my last incarnation."

Paul had gotten used to her coming out with cockamamie statements like that, and had even begun to look forward to them. Clara was a nosy, busy, refreshingly vulgar woman, which suited Paul just fine. He had never been able to stand the sweet and earnest types.

Paul looked forward to her daily visits. She clomped in, huffing and dropping several bags from each shoulder. Paul had noticed she had a grassy, milky odor that was not unpleasant. The first time she'd come she'd undone the dressing, looked at the oozing crater, and exclaimed, "Jumpin' Jesus! That's nasty!"

Paul had known then that they'd get along fine. He watched her carefully as she cleaned and rebandaged the stump. She wasn't one of those who surreptitiously held her breath. She just acted like she was peeling carrots or something equally mundane. She snapped on her gloves, laid out her gear, and got down to business. This involved scolding the wound, as if it could hear.

|

|

"What's your problem?" she muttered, wiping the pus away.

"Yuck," she exclaimed, cutting off a snippet of dead skin.

"Take that," she gloated, applying her solution of peroxide and water.

"And that!" she concluded, spanking silvadene on with a tongue blade.

Jeremy and Paul would both watch the whole thing with rapt attention. Only when she was done would she turn her attention to them. "You still popping pills like M&Ms?" she asked Paul.

"What am I supposed to do? It hurts," answered Paul.

"Hurts smurts," she said. "You're using the pills and booze for more than just the pain in your knee. And believe me when I tell you that's not the recommended treatment for depression."

"I ain't depressed," Paul said, stoutly. Clara wiggled her eyebrows and swiveled her gaze on Jeremy. "He isn't depressed," she said to Jeremy. "It's just that he can't sleep, he has no appetite, he doesn't want to do anything, and he's evil as a wet hen." Jeremy laughed at that one.

"Can I borrow this?" she asked, holding the book up.

"Sure," said Paul.

And then, no doubt purposely, she'd crammed all her equipment back in her bag and left the book where she'd dropped it. It was Jeremy who'd begun reading it.

Paul pretended not to notice, but he was pleased. The kid needed to learn a little bit more about real life. Until he began to stay with Paul, he had spent 12 hours a day on his computer. He didn't go to college. He didn't work. He didn't have a girlfriend. He seemed gripped by a strange paralysis. Paul's son, David, was worried about Jeremy. He told Paul that it had to be unhealthy, to be so close to a machine. He seemed embarrassed, admitting this to Paul. Paul had a feeling David was relieved to have Jeremy come stay with him. In this way David had lumped two of his problems together, which made each easier to ignore.

The pills make Paul sleepy and he dozes off. When he wakes he isn't sure how much time has passed. The light is still on and the kid is in the chair, but he's fallen asleep. The book has slipped to the floor.

Paul lies there quietly for a moment. Then he inches sideways till he is on the edge of the bed. His arms are strong from years of making up for the lost leg. He uses them to lower himself to the floor, in the space between the kid's cot and his bed. He lies there for a moment, listening. Then he crawls under the cot and out the other side. He looks to his left. The kid's still dead to the world. Now he must cross the open space between the cot and the door.

There was a time, on Iwo Jima, when he'd crawled towards a cave where several Japs were holed up. There was a volcanic ridge on the island that was full of caves and littered with sharp stones and boulders. There was a tunnel system connecting many of the caves. The marines hadn't known this at first. They'd systematically cleaned out cave after cave and thrown explosives in to block them. They'd moved south, taking the island foot by foot. Behind them, the medics had begun to set up temporary aid stations, and jeeps had come in with supplies.

Then, suddenly, Paul and his men were attacked from the rear. The kick-ass Texan who was next to Paul had been hit in the head and killed. Paul had rolled away into a rock-strewn gulch. DeDe, a new guy, had been hit in the leg. He began to scream. Paul turned and began a blistering fire in the direction from which the bullets had come.

"Crawl, you asshole," he'd screamed to DeDe. But DeDe didn't crawl. He stopped screaming, as if that was enough. Paul, still firing his gun, dashed into the open, grabbed DeDe by the shirt, and pulled him to safety.

It was stunts like that that had gotten Paul made a sergeant and had earned him the nickname "Cat." He had nine lives, and he'd used up eight and a half of them.

But he knew even then that he wasn't brave. The truth was he'd lost his soul and didn't give a flaming crap if he died. This conferred a large measure of protection on him. Nor did Paul care about Dorothy back home, or his son, David, who'd just been born. He cared only about his men, especially the ones like DeDe.

DeDe's real name was Dave Donovan, and Paul loved him for the simple reason that he couldn't get used to war. He was still horrified by everything, still grieved and raged for every man who died. And most of all, he wanted to live. He was a Catholic, and whenever there was a break in the fighting he prayed, fervently, as if God would listen, even in a crappy place like Iwo Jima. He looked to Paul for protection, and since Paul had lost his own heart long ago, he fought for DeDe's heart.

Paul had bandaged up DeDe's leg. He was bleeding like a stuck pig. Paul wanted to carry him back to where the corpsmen could take care of him, but the corpsmen were getting it too. It looked like the Japs had popped back up in several of the caves that had been cleared. Paul and his men were pinned down, with Japs ahead and Japs behind.

Paul had waited for a while, wondering what the hell to do. Then he'd taken two grenades, one in each hand, and slung his gun on his back. He'd had DeDe stick some branches of the nasty, oily scrub that grew there into his belt and through his shirt and the webbing on his helmet. He'd crawled to the left, flanking the Japs. It was late afternoon, and the shadows helped conceal him. He'd crawled to within 30 feet of the cave and lobbed the two grenades into the entrance. He'd played ball and had a damn good aim. When the grenades exploded, he jumped up and ran to the cave and sprayed everything in sight. Then he'd provided covering fire from the cave so some men could get within reach of another cave. They'd used a flamethrower, and the Japs had come running out on fire. Paul had never seen hell depicted so clearly on earth. He could still picture the flailing, flaming men, running through the rock-strewn, smoky landscape. The rest had melted away through the tunnels, and the wounded and dead marines were carried to safety. DeDe had been shipped out on account of his leg. Paul had gotten a Bronze Star.

|

|

DeDe still visited him. He lived upstate, near Burlington, and he made the drive down once a month or so. He brought Paul whiskey, though he knew Paul wasn't supposed to drink. He brought pain pills, too—his own, which he didn't use. He had a limp. The bones had been shattered and repaired with metal plates. He told Paul he didn't give a damn about the pain in his leg, because the pain let him know he had a leg. Paul told him he felt like he had a leg, too, but it wasn't there. The doctors called it phantom pain.

The thing was, DeDe was okay. He owned a small trucking firm and had plenty of money. He'd married a nurse and had five children. His wife was plain and plump, but she had a deep streak in her. It had come from taking care of shattered men.

DeDe said he had to be okay. He owed it to Paul. Paul had saved his life several times. It was his job to make the most of it.

Paul told him he was full of crap. He hadn't died because his number wasn't up. It was sheer friggin' luck. DeDe just smiled.

"But you better keep bringin' me booze," Paul added. "Do it 'cause I'm an old marine."

"Semper Fidelis," DeDe said.

Paul inches across the stained wood of his bedroom floor. He thinks about phantom pain. He realizes that though he thinks his soul is gone, he may still have a phantom soul, and that that is almost as good as the real thing, which is invisible to begin with. His phantom soul admits there is meaning to his life, and it hurts, though it is missing. DeDe's real soul hurts because it is still there.

He rests when he reaches the kitchen. He wonders what Dot would do if he crawled into her bedroom and got in bed with her. He needs the feeling of having a body close to his. It isn't for sex—that is long gone. When Paul had come home after the war he'd tried making love to Dot, and managed it, despite his missing leg. But then she'd gotten pregnant and had a baby girl with a hole in her heart. The baby had died after a few days. Paul had never been able to have sex again, because he was afraid he could produce nothing but deformed children. Dot had accepted this, as she'd accepted everything else. Paul's only accomplishment had been surviving the war. Dot's only accomplishment had been surviving Paul.

In the kitchen, Paul pulls himself up using a chair. He grabs the counter and moves along it. He finds the pill bottles in the dark. The pain pill bottle is fatter than the others. He leans against the counter so he can turn the child-proof cap with both hands.

The cap turns out to be Paul-proof as well. He loses his balance and crashes to the floor. He lies there, amazed. He still has the pill bottle in his hand, and he opens it quickly and puts it to his mouth, shaking several pills in. Then the light bursts on and Jeremy is standing there, his mouth gaping. Neither of them says anything. They listen as Dot's walker begins its creaking progress toward the kitchen.

Paul knows the best defense is a good offense. He's learned that, for sure.

"Help me up," he barks at Jeremy. "Don't just stand there like a moron!"

Jeremy comes over. Paul hides the bottle in his pocket. Dot appears, with her perm sticking up wildly around her head. "What happened?" she asks.

"I came out here to get some crackers," Paul says.

"You should have woken Jeremy," she quavers.

"The kid was dead to the world," Paul replies. The adrenaline has given him a moment of clarity, and he wonders if this might be literally true. Or maybe the world is dead to the kid.

Jeremy is silent. He bends down and takes Paul under the arms and lifts him to a standing position. For a minute they are close, and Paul is embarrassed by his own sour smell. The kid smells like soap. He helps Paul back into the bedroom and lowers him to the bed. Dot follows with graham crackers. She leaves them on the table by Paul's bed.

"Do you need anything else?" she asks.

"No," Paul says.

After she leaves, Jeremy sits on his cot. "Pops?" he whispers.

"Yeah."

"How am I s'posed to take care of you?" he asks. "You do what you want anyway."

"I'm not a friggin' baby."

"You're a sick old man," Jeremy counters.

For some reason, this reply stings Paul.

"At least I'm a man," he says. "You're the baby."

"That's mean," Jeremy tells him. "Why do you have to be so mean?"

Paul doesn't answer.

"I know what you went through," Jeremy says. "Dad told me about it, and I've read some stuff. But Jeez, that doesn't mean you have to be a bastard. Can't you just try to be nice?"

Paul is silent.

"The whiskey and pills are making you sick," Jeremy continues. "They're making you evil."

|

|

"I've always been evil," Paul says, morosely.

"That's not true." Jeremy replies. "Dad said that Gramma said you were the sweetest guy before the war. She told him that you were always joking and laughing."

Paul hates whining, but he thinks a little whining is in order right now. He wants to make sure Jeremy doesn't rat him out. "Yeah, before the war," he mumbles.

"Well, DeDe isn't a jerk like you, and he was in the war," Jeremy says.

"You don't know the whole story," Paul replies.

"Well, tell me then."

A few hours earlier, Paul had been hoping that Jeremy would offer him just such an opening, but now he has no idea where to begin.

"DeDe was only in a few months," he says eventually. "Then he got hit in the leg and went home. I was in for three friggin' years. I hit every friggin' island in the South Pacific. I killed so many Japs I lost count." He pauses. "I wanted to die! I shoulda died. After Guadalcanal I didn't give a crap."

Paul looks up. He is surprised to see that Jeremy's cheeks are flaming, as if he's been slapped.

"I've killed men with my bare hands and liked it. I've drunk water with dead Japs in it. I've stepped on a mine and lived. Never found a bullet that could stop me. Was an animal so long I forgot that I was human."

Jeremy lays a palm on his cheek. "I'm sorry, Pops," he says.

Paul is starting to cry. He realizes that he's not faking it anymore. He has never admitted out loud what he lost in the war. It feels terrible. He dashes a hand across his eyes.

"What the crap is this? A daycare center?" he snorts.

"I'm sorry I called you evil," Jeremy counters.

"Been called worse."

"The way I see it is, you sinned for us. When people talk about sacrifice, they don't really understand what that means."

"Damn, kid, Memorial Day ain't for a month yet." Paul laughs.

Jeremy still looks stricken. Paul can't believe he is so sincere. A little more life and he'll lose his halo.

"I've thought about joining the Marines," Jeremy says.

Paul doubts the Marines would have him, but he doesn't want to hurt Jeremy's feelings, so instead he says, "Oh, hell, don't do that."

"I'm taking care of you instead."

"That's almost as bad."

"Next Memorial Day I'm taking you in the parade they have in White River Junction," Jeremy promises. "I'll push you in the wheelchair if I have to."

"Do I have any say in this?" Paul asks.

"Clara told me I should," Jeremy says. "She says you have to stop hiding from the world."

Paul is silent. He'd been in a few parades when he first came back, but they had made him sick. The crowds along the street had yelled and whistled and laughed and waved flags in a spasm of easy patriotism.

But Paul could not smile and wave as he was supposed to. He had wished that somehow every dead soldier could be transported miraculously to White River Junction. He had wished that they could be in the parade, pushed along on stretchers by those who had survived. In his imaginary parade, the people would be forced to stay there, standing, quiet, until every last dead man passed by.

This vision makes him thirsty. He reaches under the bed and pulls out his bottle. He has a slug and then dumps the stale water into the fresh water and pours the kid a few fingers of whiskey in the empty glass.

"For the dead," he says.

Jeremy drinks it like someone who's never had whiskey. He blanches.

"That'll put some hair on your chest," Paul says. He reaches in his pocket, finds the pill bottle, and tosses it to Jeremy, who actually reaches up and catches it. He lies down and pulls the covers over himself. Jeremy lies down too, and Paul hears him give a hitching sigh.

Then they both sleep.

Once again, Paul dreams he is in the kunai grass. He is surprised to be back in the dream so soon. His grandson is with him this time. He is trying to push Paul in a wheelchair, but the grass keeps catching in the wheels, so he pulls Paul up and they walk along together. Paul is surprised to find he can walk well. He looks down and finds his leg is there. He is filled with elation. He reaches down and grabs it to make sure that it is real. Then he taps Jeremy and points to his leg. He doesn't dare talk, because he knows the Japs are somewhere close by.

Jeremy laughs out loud, just like a goddamn boot. Then the bullets begin to fly and Paul pulls him down. They lie there in the grass with the bullets whining above them. Paul is embarrassed by his sour smell. He decides that if he lives he will bathe in the ocean.

He wakes then. He turns and sees that Jeremy is sitting up, with his head in his hands.

"What's wrong?" Paul asks.

"I feel drunk," Jeremy says.

"It'll pass," Paul assures him.

"I was just dreaming," Jeremy adds. "I dreamed I was in the war."

"Was there tall grass in your dream?" Paul asks, holding his breath.

"No. Trees."

|

|

Paul is relieved. He doesn't want the kid dreaming his dreams. So he doesn't admit that he's been there too.

"You know, I'd forgot about the ocean," he tells Jeremy. "We used to swim in the ocean when we could. The South Pacific was real warm. There was always a wrecked boat or two in the bays where we swam. We used to dive off of them."

"Was it fun?" Jeremy asks.

"Yeah, it was," Paul says.

He remembers how a guy from Mississippi used to pretend to baptize them. He'd hold them under and yell out a prayer. Paul can still say it:

Dear God, if this jarhead bites the dust,

Take him to heaven because you must.

If you don't then you just wait,

He will storm the Pearly Gates.

Suddenly he sees DeDe above him, on a rusted Higgins boat. He is bare-ass; they all are.

"Look," DeDe yells. "I'm gonna do a cannonball." He pulls his knees to his chest, wraps his arms around them, and jumps. The water leaps up around him.

When he pops to the surface, Paul pretends to scold him. "Don't you do anymore cannonballs," he says. "We've had a friggin' nough of them." And then everyone laughs—laughs and howls as if their hearts aren't breaking.

Smith is a psychiatric nurse at DHMC, as well as a much-published author of both poetry and prose. Her work has appeared several times previously in Dartmouth Medicine and also in Yankee, Ancestry, Byline, Worcester Review, Larcom Review, Cumberland Poetry Review, and The Sun. She was recently nominated for a Pushcart Prize, which honors the writers of short stories, essays, and poems first published by small presses and magazines nationwide; the award is considered a touchstone of literary discovery. This story is totally fictional, but the pictures accompanying it are actual World War II photographs.

"Together we make it happen"

The DHMC-affiliated White River Junction VA both serves its patients and contributes significantly to Dartmouth's educational and research missions.

By Jonathan Weisberg

Paul in the adjacent story is a fictional character, but no one at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in White River Junction, Vt., would be surprised to see him come through the door. His struggles with the physical and psychological wounds of war are not unusual there. Though he may be a fabrication, his problems are very real.

All VA patients, by definition, share with Paul his status as a veteran. In fact, the bulk of patients seen at the White River VA are aging males who served in World War II or the Korean War, although Vietnam veterans are a growing contingent. Not surprisingly, the system has particular expertise in treating the kinds of chronic injuries that result from battle, such as Paul's leg. Furthermore, it has various special programs that one can imagine patients like Paul benefiting from. One is a three-week treatment program for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that served more than 1,200 patients in 1999. The mental health division in White River also provides substance abuse treatment, including a concentrated program called Quitting Time; it logged 1,421 visits last year.

But inpatient treatment for illness and injury accounts for only a portion of the activity there. The mission of the VA medical system is to provide veterans with the whole gamut of health services—"primary care, specialized care, and related medical and social support services."

The notion of how to provide this care and whom to provide it to has been in flux recently, however. The VA's original mission was to care for veterans with illnesses and injuries directly related to or aggravated by their military service. The VA was then opened to indigent veterans who didn't have the means to pay for care elsewhere. Within the last two years, VA services have been accessible to all veterans. "We are here, our doors are open," is how Gary De- Gasta, director of the White River facility, puts it. Now, depending on individual veterans' circumstances, the costs of their care are borne by the VA system itself or are reimbursed by third-party insurers.

At White River, this expansion effort is reflected in the "20,000 for 2000" campaign, which is aiming to raise the number of enrolled veterans to 20,000 by the end of the year. There are now 15,400, drawn from an estimated pool of 100,000 veterans in Vermont and part of New Hampshire.

The means by which care is delivered have also been shifting radically, both nationally and locally. The VA is moving away from a hospital-based model of health care toward a geographically diversified outpatient model. It is a move driven both by cost concerns and by new technologies that allow more procedures to be performed on an outpatient basis. At White River Junction, this has resulted in a 39% increase since 1995 in the number of outpatient visits, as well as a decrease in the number of active beds—from 150 to 60. The VA is also developing outpatient clinics located closer to where patients live, including Burlington and St. Johnsbury, Vt., and plans to establish further such clinics in the years to come. That way, "people 100 miles away don't have to come to White River Junction for their primary care," says DeGasta.

With this sort of fundamental change occurring, a degree of turmoil was probably inevitable. A recent funding crisis at the White River VA pointed up both the loyalty of its patient population and the interdependency of the VA with the other institutions that make up DHMC.

The budget crisis began in the fall of 1998, with a threatened $8.7-million drop in the facility's funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs. White River administrators speculated that the only way to absorb a cut that big would be to close the surgery department. This would have eliminated almost 100 jobs and some services for veterans, as well as DMS training sites. Patients rallied and DHMC officials stepped in. The resulting concern led to front-page stories and editorials in the regional press and drew the attention of Vermont's entire congressional delegation. Pressure from the legislators and the community eventually drew a commitment from the national VA leadership to fund the White River inpatient service indefinitely—but meanwhile people had time to think about what would happen if the VA weren't there, or were there only in a much-diminished form.

|

|

|

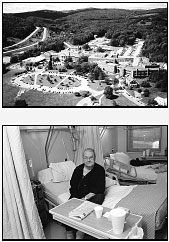

The White River Junction VA is home to both inpatient

(right) and outpatient (above) programs,

as well as considerable research and education. | |

Besides being an essential element in the health care of veterans, the VA plays a significant role in the training of Dartmouth medical students and residents. The physicians on the staff of the White River VA are all members of the DMS faculty. Dartmouth medical students do 40% of their clerkships at the VA, including rotations in medicine, surgery, psychiatry, and primary care. And two-thirds of DHMC residents rotate through the VA, helping with patient care and receiving training on both the inpatient and the outpatient services. In fact, the decision back in 1946 to place Dartmouth residents at White River was instrumental in the subsequent expansion of DHMC's residency programs, in the 1970 reintroduction of a full M.D. program, and in the 1973 creation of Dartmouth- Hitchcock Medical Center.

The White River VA is also the site of a significant research enterprise. For Dartmouth investigators, this offers opportunities for formal collaboration as well as general synergism. Fifty-four principal investigators at the VA are working on roughly 140 different projects with total research expenditures of $4.7 million in FY99. The funding comes primarily from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institutes of Health. The bulk of the research is in the basic sciences, including projects on environmental contaminants and the molecular aspects of cancer, arthritis, and arteriosclerosis. There is also a strong program of outcomes research and a one-year fellowship in the field. Several clinical trials are underway as well, including two related to Persian Gulf War illness.

And White River is the home of four national VA programs—the National Center for Clinical Ethics, the National Quality Scholars Program, the Center for Learning and Improvement of Patient Safety, and the National Center for PTSD.

Just as Dartmouth benefits from the association with the VA, DeGasta notes that the VA's association with Dartmouth is "absolutely critical to delivering quality health care to veterans." He says the association with a first-rate academic medical center allows the VA to recruit physicians who would not otherwise be attracted to a rural area.

"I think that this is a classic example of the VA and its academic affiliates acting together to do what we should be doing," DeGasta adds. "We want to deliver quality health care, the Medical School is interested in solid academics and research—and together we make it happen."

Weisberg is Dartmouth Medicine's editorial assistant.

Paul remembers being bent

at a jungle pool, sucking up

water after hours of

tormenting thirst. He then

heard a long, rising squeak

and looked up to see a body

rising up through the algae,

releasing a pocket of gas.

Paul remembers being bent

at a jungle pool, sucking up

water after hours of

tormenting thirst. He then

heard a long, rising squeak

and looked up to see a body

rising up through the algae,

releasing a pocket of gas. Suddenly, Paul and his men

were attacked from the rear.

The kick-ass Texan who was

next to Paul had been hit

in the head and killed. Paul

had rolled away into a rockstrewn

gulch. DeDe, a new

guy, had been hit in the leg.

Suddenly, Paul and his men

were attacked from the rear.

The kick-ass Texan who was

next to Paul had been hit

in the head and killed. Paul

had rolled away into a rockstrewn

gulch. DeDe, a new

guy, had been hit in the leg. Whenever there was a break

in the fighting DeDe prayed,

fervently, as if God would

listen, even in a crappy place

like Iwo Jima. He looked to

Paul for protection, and since

Paul had lost his own heart,

he fought for DeDe's heart.

Whenever there was a break

in the fighting DeDe prayed,

fervently, as if God would

listen, even in a crappy place

like Iwo Jima. He looked to

Paul for protection, and since

Paul had lost his own heart,

he fought for DeDe's heart. "I was in for three friggin'

years," Paul tells his

grandson. "I hit every friggin'

island in the South Pacific."

He pauses. "I've killed men

with my bare hands and liked

it. Was an animal so long I

forgot that I was human."

"I was in for three friggin'

years," Paul tells his

grandson. "I hit every friggin'

island in the South Pacific."

He pauses. "I've killed men

with my bare hands and liked

it. Was an animal so long I

forgot that I was human." Paul is silent. He'd been

in a few parades when he

first came back, but they

had made him sick. The

crowds along the street had

yelled and whistled and

laughed and waved flags in a

spasm of easy patriotism.

Paul is silent. He'd been

in a few parades when he

first came back, but they

had made him sick. The

crowds along the street had

yelled and whistled and

laughed and waved flags in a

spasm of easy patriotism.