In neonatal care, is more too much of a good thing?

"The more the merrier" can be said of friends, of flowers, and of fresh-baked cookies. But not of neonatal specialists, according to a pair of recent DMS studies.

One team of researchers, led by pediatrician David Goodman, M.D., showed that newborns in intensive care units have a nearly uniform mortality rate, despite varying resources across the country. And a related study, led by Lindsay Thompson, M.D., compared neonatal outcomes in the U.S. to those achieved in three other countries.

Due to vast technological improvements— from new drugs to ventilators designed especially for babies—as well as to an increase in the number of neonatologists, a premature newborn's chance of survival has improved dramatically over the past 30 years. But a continuing increase in the supply of neonatologists and neonatal intensive-care resources may not be efficacious. "We seem to have reached the point where more neonatologists do not lead to further decreases in newborn mortality," explains Goodman, an associate professor of pediatrics and of community and family medicine.

|

Photo: Jim Cole / AP |

|

Photo: Flying Squirrel Graphics |

|

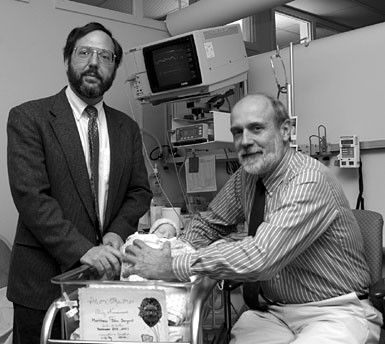

Lindsay Thompson, in the left photo, and David Goodman (left) and George Little (right), in the right photo, spend a fair bit of

their time in DHMC's neonatal intensive-care unit, but they have raised questions about the proliferation of such units. |

Data: Goodman and his team collected data on the nearly 3.9 million infants born in 1995 with a birth weight of more than 500 grams (1.1 pounds). They then broke the U.S. into 246 neonatology service regions and divided the regions into five groups—very low (for a very low ratio of doctors and beds to babies), low, medium, high, and very high. Then they looked at the association between resources and deaths.

In "low" areas (which had 4.3 neonatologists for every 10,000 births), the mortality rate was 7% less than in "very low" areas (which had a 2.7 ratio). But once the supply of neonatologists exceeded the "low" level, there was no significant difference in mortality. Low areas, with a 4.3 ratio, had nearly the same mortality rate as very-high areas, with an 11.6 ratio. There was also no difference in mortality as the number of neonatal intensive care beds increased.

Whether more neonatologists and neonatal beds are beneficial in other ways remains unknown, but from a mortality standpoint "sheer numbers of beds or neonatologists don't make much of a difference," says Goodman. The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Spectrum: Thompson's study, which was published in Pediatrics, compared the whole spectrum of neonatal care in the U.S.—from pregnancy to birth to specialized care after birth— with that of three other countries: Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom. She found that the U.S. has far more neonatal intensive-care resources, puts less emphasis on prenatal care, and has a lot more lowbirth- weight, at-risk babies. The other three countries have fewer neonatal resources, put more emphasis on prenatal and reproductive care, and have a lot fewer at-risk babies.

Of the four countries, the U.S. has 40% more neonatologists than the next-best-staffed country, Australia, even after accounting for the greater number of high-risk babies. The U.S. has 8.0 neonatologists per 1,000 lowbirth- weight births, whereas Australia has 5.7, Canada has 5.5, and the United Kingdom has 3.7. But neonatal mortality rates are about the same in all four countries; the U.S., with more resources, does no better.

"It really challenges our kind of current health-care system, which is expanding neonatal intensive care," says Thompson, an instructor in pediatrics. "It looks to me that we probably don't need to expand it anymore."

Thompson believes the U.S., which has some of the highest rates of unintended pregnancies and of low-birth-weight babies among industrialized nations, needs more prenatal services and better funding for and access to reproductive care. "Neonatal intensive care is high technology at its best. . . . You see these tiny babies hooked up to lots of machines— it's very expensive and it's very successful up to a point." Unfortunately, she adds, "the benefits are a lot more obvious when you save one baby compared to making sure that hundreds of thousands of women receive adequate prenatal care."

Trend: Pediatrician George Little, M.D., who was a coauthor of both studies, says the growth of neonatal intensive care in the U.S. has happened without explicit public planning or solid accountability. He says the trend away from accountability and toward deregulation is similar to what has happened with airlines, banks, and utilities.

"Accountability is fundamental," maintains Little. "The question we need to ask about neonatal intensive care is 'Are we really getting the most out of this as we should?'"

Matthew C. Wiencke